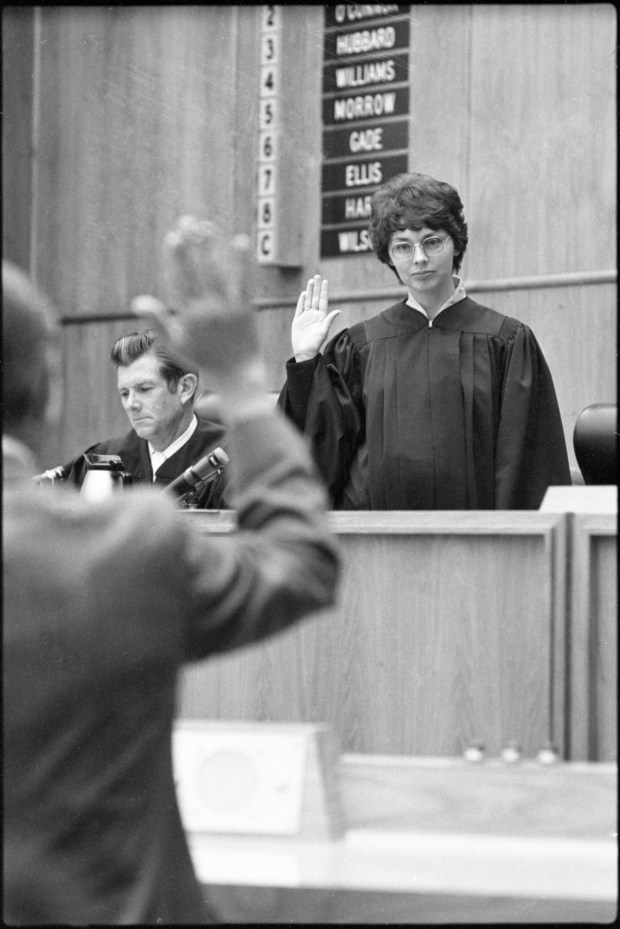

When Janet Kintner was sworn in back in 1976, she was a rarity: a female judge. There was just one other female judge on the San Diego Municipal Court bench when then-Gov. Jerry Brown appointed her.

Kintner was also visibly pregnant. But there was no such thing as maternity leave for a judge, she recalls. She used her entire three weeks of vacation time when she had her first child, then headed back to work.

Kintner spent 31 years on the bench, overseeing civil trials and criminal cases before retiring as a San Diego Superior Court judge in 2007. COVID stay-home orders coupled with an online memoir writing class led her to pen her reflections.

Kintner’s memoir, published through She Writes Press, is titled “A Judge’s Tale: A Trailblazer Fights for Her Place on the Bench.” It strips away the mystique of being a judge and offers a candid look at her personal life through 1978 — a notable time, she said, because that year marked the first time she had to run for re-election to her judicial seat. Two men were challenging her for the spot, and she had work to do.

In winning that election, Kintner says she became the first female judge in San Diego to be elected to a judicial seat in a contested race. (Other female judges had won re-election, but had run unopposed.) Her days saw her campaigning at breakfast meetings, racing to court to oversee cases, home at lunch to see her toddler, then back to court. While pregnant. And always in a skirt.

And before the end of that hard-fought re-election campaign, she would give birth to her second child. And again, no maternity leave for a judge. It was three weeks of her vacation time, then back to work — mother of a 2-year-old and an infant, nursing the little one at lunch when she could, finding time to breast pump when she couldn’t and grateful that the black robe was forgiving when her milk leaked.

In an interview with the Union-Tribune, Kintner, 81, said her book addresses “what it was like for women then, and why it’s important for women to be in positions of power.” She wants to preserve those stories lest they be lost to time.

She wrote of the internship where she spent her days typing up legal documents written by male lawyers, while a male intern was allowed to do research. She recalled the time when even a courtroom bailiff didn’t believe she was an attorney.

She started out as a new attorney who wanted to “right the wrongs.” But opportunity was scarce. “It was very difficult to get a job as a lawyer as a woman in 1968 and ’69,” Kintner said. She said law firms flat-out refused her because she was a woman.

She finally landed a job with Legal Aid, where she worked to help low-income people victimized by consumer fraud. That two-year stint led to a job offer from the San Diego City Attorney’s Office, where she created its first consumer fraud unit. Such cases were so much a novelty, they sometimes drew coverage in the local press.

In late 1974, she made a short foray into private practice — a job change notable enough to draw a mention by Neil Morgan in his San Diego Evening Tribune column, where he credited Kintner as the one who filed the city of San Diego’s first consumer fraud protection case.

In 1975, Kintner said she and a group of female lawyers got to talking, lamenting about unfair treatment by male judges and agreeing that the bench should include more women — there was just one female judge, not just on San Diego Municipal Court but the entire county at the time. A colleague turned to Kintner and asked if she’d submitted her name for the governor to consider for an appointment.

“I said, ‘No.’ And she said, ‘Well, you can’t complain if you don’t put your name in,’” Kintner recalled. “So I did. And I thought, well, at least I can complain now.”

Janet Kintner is sworn in to the San Diego Municipal Court as a new judge in 1976. (The San Diego Union Tribune / San Diego History Center)

Janet Kintner is sworn in to the San Diego Municipal Court as a new judge in 1976. (The San Diego Union Tribune / San Diego History Center)

She applied and was screened. The surprising call from the governor’s office for an interview would follow. Kintner was appointed to Municipal Court in early 1976, and another woman was appointed to the bench in South Bay, bringing the number of active female judges in the entire county to three. (That number does not include the county’s first female judge, Madge Bradley, who had retired in 1971.)

As a young adult, she was the victim of sexual assault when a stranger broke into her apartment. She reported it, but did not get justice — “which meant the community did not get justice,” she said. Now a judge, she wanted to ensure justice for women. She recalled early in her judicial career, for example, talking with a male judge who scoffed at the idea that a woman had been raped because she had consented to sex with an intruder who’d broken in and threatened to kill her infant.

“I thought it was really important to have more women on the bench who would not fall for that,” she said.

In the years that followed, the makeup of the bench locally and statewide grew more diverse to include people of color and women. “And once we got more,” she said, “it became easier to be one.”

In the book, she changed the names of a few people, including her election opponents and some fellow judges, for privacy reasons. But she also writes about real friends such as “Judy” — who was Judith Keep, the first female federal judge in San Diego County and the woman for whom the San Diego federal courthouse is named.

In the old days, lawyers saw her as “the woman judge,” she said. “Now they see the women judges as individuals, because there’s more of them. And that’s good.”

Approaching 50 years since Kintner’s appointment, female judges make up just shy of half the bench in San Diego Superior Court. Of the 134 filled judicial seats, 65 of the judges are women.

“We have made huge strides, but can’t take them for granted,” Kintner said. “We don’t want to go back.”