An elderly couple huddled over a long to-do list.

“So you’re going to cash the check …,” said 75-year-old Warren Wiscott.

“And then go get groceries,” finished Winona Wiscott, 72. “Then you can go to the pawn store.”

A voice booming out of a nearby speaker added another worry: “Do not leave your cash just sitting out somewhere because someone may come and take it.”

The cash, luckily, wasn’t real. Nor were the Wiscotts: Warren and Winona were only characters assigned to Amy Zuill-Smith and Anna Maybury, who in real life are 37 and 49. However, the hurdles they faced trying to pay for food, rent and other necessities were anything but fiction.

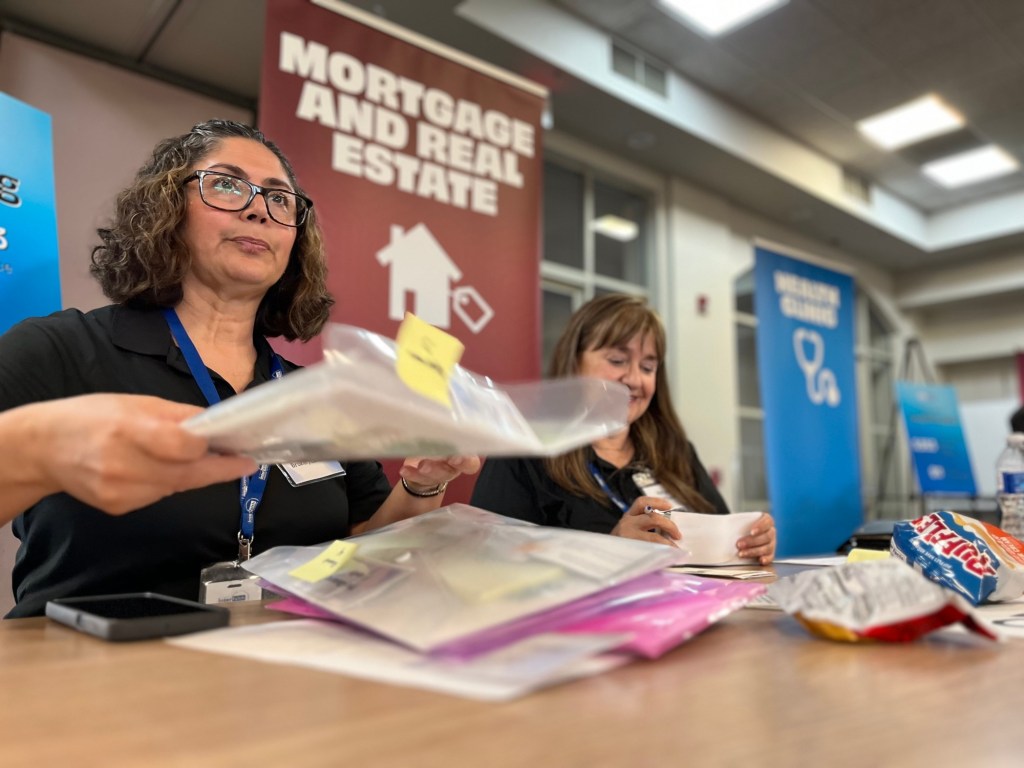

Zuill-Smith and Maybury were participating in Interfaith Community Services’ Empathy-Building Experience, an interactive simulation of what countless low-income and homeless San Diegans deal with daily. While versions of the program have been around for years, Interfaith recently revamped the effort and is now offering the experience to high schools, churches and other organizations. More than 100 people filed into Rancho Bernardo Community Presbyterian Church one Thursday in October to take part.

The simulation is meant to replicate four weeks of tough choices. Some participants were ordered to track down things like utilities and child care, which could be found at booths managed by others in the room. The “employment center,” for example, came with specific instructions for those in charge: You were only allowed to hire a certain number of people, adults who came with “kids” weren’t eligible for job interviews and anybody might be turned away for any reason.

The first “week” began. It would last ten minutes.

Zuill-Smith rushed to the bank. Maybury headed to the pawn shop. She thought selling a video game console would net $300, yet the place gave her a mere $130. Maybury then hustled to a Quick Cash, a food pantry — where she was turned away — and an aid organization. The latter gave her an application to fill out but the timer expired before she could finish.

“Venders, close your booths,” said the voice in the speaker. “No need to be polite.”

Week One was over. Before the next week began, the voice had more bad news: “Unfortunately, the school has had a gas main break and will be closed for the first three minutes of Week Two.”

This affected Kadri Webb and Justin Apger, two Interfaith board members playing a 9-year-old and a 12-year-old. With classes cancelled, their “mom” opted to leave the two alone at home. This worked for a few moments until a woman wearing a police badge walked up.

“I’ve been told there are children here that are neglected,” the woman said. “I need you two to come with me.”

“I’m not going,” Webb responded.

The standoff lasted until the gas leak was fixed. The kids fled to school.

The simulation took on extra significance amid the government shutdown. The food assistance program CalFresh in particular was then expected to run out of money, which could have hurt hundreds of thousands of people just in San Diego County.

“San Diego’s an expensive place to live in normal times,” U.S. Rep. Scott Peters, a Democrat from La Jolla, said in a brief interview at the event. “But this is a tough time.”

Peters showed up partially to announce he was giving money to Interfaith’s People for People Fund, which is able to match donations up to $1 million because of a gift from Price Philanthropies. Nonprofit staffers said they hoped to raise enough to weather any federal budget cuts.

Other elected leaders attended as well, including Escondido Mayor Dane White, his presence a small yet significant sign of the improved relations between his city and Interfaith after a long period of tension.

During Week Three of the simulation, the daycare shut down because of a COVID outbreak and a landlord walked around the room to see if anyone had failed to pay rent. No rent meant an eviction. Week Four was just as tough.

At the end, participants reflected on the sheer stress of it all.

Webb, the board member who played a 9-year-old, said he found himself getting mad at his mom for putting him in a bad situation, even though he knew it wasn’t really her fault. Several people marveled at how complicated transportation can be when you don’t have a car.

One woman thought about the times she’s been in line at a bank or grocery store and heard people grumbling around her. Maybe they were simply impatient, she told the room. Or perhaps they had only a few more minutes to get to their next crucial errand.