Miranda Snyder is struggling to pay $1,154 for six parking tickets she has incurred since July for leaving her RV — the only home she can afford — parked on San Diego city streets and lots overnight.

The city doubled the fines she owes for four of them because she didn’t pay them on time. She said she has asked the city for weeks for a payment plan. She hasn’t heard back.

The city’s parking citation payment website also tells her that her RV could be towed for five of her citations. So during the 12 hours every day that she’s out working as an accountant, she fears she could come home from work and find her RV gone — with her dog and three pet rats inside.

“I’m … just praying every day that my RV will be there,” Snyder said. “I’ll go through hell to make sure that they’re okay.”

The city of San Diego is on track to issue millions more dollars in parking citation fines this year than it has in recent memory, after raising their prices last April for the first time in 21 years to adjust for inflation and to help close the city’s budget deficit.

In the first 10 months of this year, officers issued more than $33 million in parking citation fines, well above the $29 million issued last year, The San Diego Union-Tribune found in its analysis of parking citation data published by the city treasurer.

But even as the city issues millions more in fines, it doesn’t collect all the money it charges.

The city is missing out on hundreds of millions in fines, fees and other missing payments due because people are not paying them, whether by choice, error or — as is the case with Snyder — because they say they can’t.

The city treasurer’s Delinquent Accounts program, which handles debt collection for the city, is still trying to recover about $123 million worth of parking citations and penalties from months and years past, according to data from the city treasurer’s office as of early November.

Altogether, the treasurer is currently trying to recover about $264 million in delinquent fines, fees and missing payments the city is owed.

Parking citations make up the single largest category of delinquent debts. About a quarter of the nearly half a million parking citations that were issued last fiscal year still have not been fully paid, a city spokesperson said.

Other types of delinquent debts include unpaid ambulance transport fees, which cost patients anywhere between $1,200 and more than $3,100 per ride, as well as water and sewer utility fees, fire inspection fees, “cry wolf” fines for false fire alarms and business taxes, such as residential rental taxes.

As of early this month, the city had recovered 31% of all delinquent debts in its system, which the city treasurer’s office said is above industry average. That number counts both paid and canceled debts as recovered debts.

Fines are meant to serve as deterrents of unwanted behaviors, and it’s also common for cities to use them as a revenue generator, said Heidi Goldberg, director of economic opportunity and financial empowerment for the National League of Cities.

But when fines are imposed on people who can’t afford them, they won’t help cities financially, Goldberg said. At a certain point, it could cost cities more money than they actually get back.

“If they’re continually issuing fines and fees on people who cannot pay them, then they’re losing money in the end,” Goldberg said.

It also raises questions of equity, as growing fine debts can plunge people already experiencing poverty and homelessness deeper into financial hardship.

“We provide multiple opportunities for debtors to resolve their obligations by offering flexible solutions,” a city spokesperson said in an email. “We strive to balance the need for revenue recovery with fairness and compassion for debtors and their individual circumstances.”

When you don’t pay a ticket

San Diego parking fines rise steeply if you leave them unpaid.

If the fine goes unpaid for 35 days, the amount owed doubles as a late penalty, except in the rare case that the initial fine was $300 or more.

By day 56, another $10 late fee is tacked on.

After day 72, the debt is forwarded to the city treasurer’s Delinquent Accounts program, where the debt will start to accumulate 7% annual interest.

At that point the city also places a hold on your vehicle’s registration at the DMV.

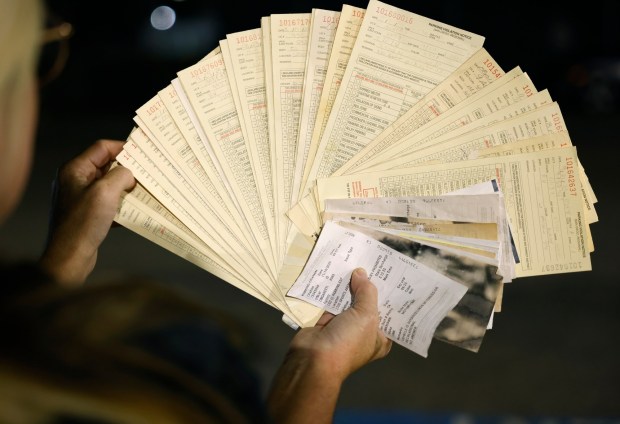

Miranda Snyder, who lives in an RV, holds some of the tickets she has gotten from parking overnight on a city street. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Miranda Snyder, who lives in an RV, holds some of the tickets she has gotten from parking overnight on a city street. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Parking ticket debts are not reported to credit agencies, but the city can report other types of debts, including business taxes and transient occupancy taxes. The city also refers some debts to the Franchise Tax Board for intercepting tax refunds.

The city’s goal is to recover as much as possible, officials said. But if a debt goes unpaid long enough, the city will deem it uncollectible and cancel it, as the cost of recovering the debt may be higher than the debt itself.

The city treasurer’s office has delinquent accounts going back as far as 1983. The office does not yet have a policy or process to determine which debts are uncollectible; it is currently working on one.

That doesn’t necessarily mean people can get away with no consequences for not paying fines if they just wait long enough.

For example, the hold on DMV registration means the vehicle can risk getting towed — the city says it may impound vehicles for expired registration and violations of rules requiring a vehicle be moved every 72 hours.

For people living in their vehicles, that would mean losing their home.

More than 1,000 tickets for RVs

The success of cities’ debt collection efforts often depends on whether the people getting the fines can afford them.

That issue has garnered attention as the city has ramped up enforcement of its rules prohibiting overnight parking of RVs and other oversized vehicles on city streets and lots.

The enforcement, which resumed in July, has especially impacted homeless people living in their RVs, many of whom say the tickets are penalizing them for not being physically or financially able to park their RVs elsewhere.

The city, however, has said that everyone must abide by parking laws regardless of housing status, and that those laws are necessary to uphold quality of life in neighborhoods “heavily impacted by residents and visitors,” especially the city’s beach communities. The city gets hundreds of complaints each year about trash and lack of public parking access resulting from RVs in beach and bay areas.

The city offers homeless residents a free parking lot at H Barracks, which opened in July, with more than 100 spaces for people to park their RVs during nighttime hours and services to help people climb out of homelessness.

City officers offer people in RVs the chance to move to H Barracks to avoid getting cited. But relatively few people have gone to the lot — on average, only about 29% of its spaces were used in September.

That’s largely because many say it’s logistically inaccessible to them, since they would have to move their RVs out of the lot every day. Many of their vehicles need repairs or are difficult and expensive to move each day — they get only about four miles to the gallon.

That’s the case for Veronica Flood, who lives in her RV and has been disabled ever since she got into a severe car accident at 24 years old. Her only income is about $1,300 a month in Social Security.

Flood has several unpaid parking tickets for having her RV parked on city streets and lots overnight, but figuring out how to pay them has taken a back burner to figuring out how to keep herself fed.

“Honestly, I haven’t even thought about it too much. I try not to focus on things out of my control,” she said.

As few take advantage of the H Barracks lot, police officers issued more than 1,100 oversized vehicle citations from July to mid-October.

That’s in addition to 3,000 citations for other parking violations that homeless people living in their RVs also commonly receive, such as violating posted signs that prohibit overnight parking in public lots.

Are fines working?

When evaluating whether a city’s fines and fees are effective and equitable, Goldberg recommends that cities ask themselves some questions:

Are the fines actually working? Are they reducing the behavior the city wants to deter? Who is most affected by the fines? Does trying to collect the debt cost more than it’s worth? Would a lower fine or fee be more likely to get paid?

Miranda Snyder has received a number of overnight parking tickets but can’t afford to pay them. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Miranda Snyder has received a number of overnight parking tickets but can’t afford to pay them. (K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Some cities have changed the way they issue court-ordered fines, such as traffic violations, to consider the person’s ability to pay. Other ways cities can offer help to debtors include offering financial coaching, connections with public benefits like food stamps, payment plans or a sliding scale for fees and fines, Goldberg said.

One main source of help that San Diego offers in paying off parking citations is a payment plan option.

Generally, the plan is only available to low-income people who are either at or below 200% of the federal poverty line — the federal poverty line is $15,600 a year for a one-person household — or who receive a government benefit payment, such as food stamps, Social Security or CalWORKs.

Those who qualify for a low-income payment plan can pay $25 or less each month, will have their late fees and penalties removed and have up to 24 months to pay off the fine. Enrolling in the payment plan costs $5.

But few people are on a city payment plan, the city treasurer’s data show. About 700 debt accounts — for all kinds of debts, not just parking citations — are currently on a payment plan, out of 1.2 million delinquent accounts in the treasurer’s system, a spokesperson said.

The city said it doesn’t have data on how many applications have been received and denied for a payment plan — but it says most who apply are approved.

As for Snyder, she said she has been emailing the city over the past three weeks asking for a payment plan and hasn’t heard back yet.

She doesn’t qualify for a low-income payment plan because she makes too much money with her accounting job.

She could qualify for the city’s standard payment plan, though it won’t erase any late penalties and it requires a $20 fee. And she won’t be able to use the standard payment plan for any tickets that have already been marked as delinquent.

Snyder estimates she has gotten about 75 parking tickets in the three years she has lived in her RV. She just paid off more than $700 worth of parking tickets in September to lift the city’s hold on her DMV registration.

Every new parking ticket she gets forces her to choose the lesser of two evils: put off paying her credit card bill and incur more credit card debt to pay the ticket, or put off paying off the ticket and incur ticket penalties to pay her credit card bill.

Snyder moved into her RV after her seamstress business collapsed during the COVID-19 pandemic. She was jobless for six months and lived off credit cards, ruining her credit score.

She can’t secure an apartment and hasn’t found an RV park she can afford or that will allow her older RV. And she can’t drive it in and out of H Barracks daily because it has a leaking carburetor she hasn’t found anyone to fix.

“Even though I’m not paying rent, I’m paying deeply in other ways,” Snyder said. “When it comes to the RV people, they’re trying to squeeze blood from a stone.”