The California Coastal Commission, which often doesn’t permit shoreline armoring for private properties along the coast, recently approved brand new seawalls for structures in Pismo Beach and Cayucos.

The two properties passed the hurdle because they existed before the Coastal Act became effective in 1977.

“They weren’t set back from the shore, and they weren’t subject to the Coastal Act’s requirements,” the commission’s Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn said. “Essentially, grandfathered in or given certain rights that the other development isn’t because they may be located in harm’s way and it’s a matter of fairness that they are potentially allowed to armor themselves.”

At its Oct. 10 meeting, the Coastal Commission retroactively authorized a permit for reinforcing a damaged seawall in front of a residence on Pismo Beach’s Naomi Avenue. The permit also ratified filling four sea caves with grout.

The property owners carried out the repairs after the damage occurred during 2023’s winter storms. The deluge of rain battered the seawall they had installed in 1992. The erosion around the property also disintegrated the bluff’s interior, resulting in sea caves that required plugging.

The property owners didn’t respond to New Times’ requests for comment.

CRUMBLING SUPPORT A home in Cayucos gets approved to build a seawall that will save it from bluff erosion, but not all coastal properties get the same treatment from the California Coastal Commission. Credit: COVER PHOTO BY JAYSON MELLOM

CRUMBLING SUPPORT A home in Cayucos gets approved to build a seawall that will save it from bluff erosion, but not all coastal properties get the same treatment from the California Coastal Commission. Credit: COVER PHOTO BY JAYSON MELLOM

Kahn told New Times that the Coastal Commission issued the applicants an emergency permit at the time because their home was in danger from the erosion. The emergency permit required them to apply for the follow-up permit later, which recognizes that the reconstruction took place.

“This is a repair to an existing [seawall], but it’s a form of repair,” he said. “Our analysis is that the degree of repairs is such that we basically consider this to be new, to be replaced.”

Under the Coastal Act, there are two other uses where shoreline armoring is permissible.

“The second use is public beaches in danger from erosion,” Kahn said. “The idea there is building a groin or a jetty that can hold sand, and that can keep beaches up for a certain width. That’s more common in Southern California than in Northern California.”

Shoreline armoring is also allowed for coastal dependent uses, like when marine research facilities or boating facilities are required to be on the water or immediately adjacent to it to function.

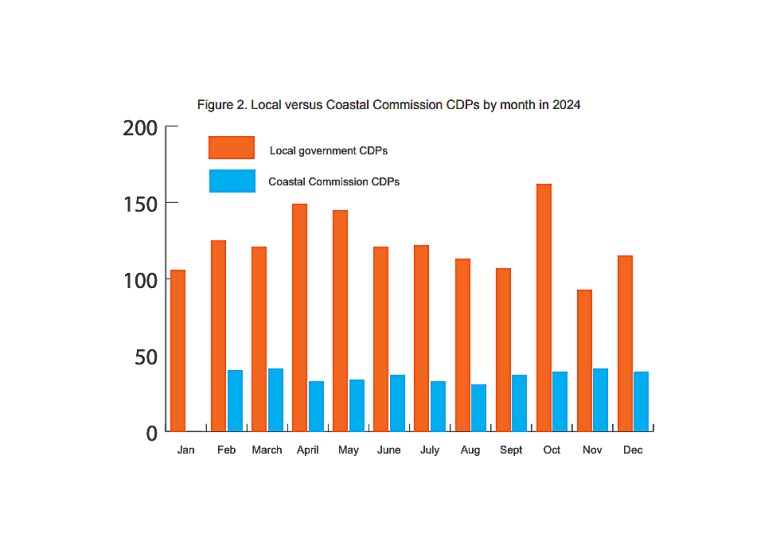

Every year, hundreds of coastal development permit applications hit the Coastal Commission’s desk for approval. On top of that, California city and county governments issue more than 1,000 such permits annually, according to the Coastal Commission’s 2024 key metrics report. The Coastal Commission tracks those local coastal permits and hears a few dozen project appeals a year.

Getting a seawall and other kinds of shoreline armoring approved is tough.

Frequent rejections of permit applications are underpinned by a larger tussle where state and local agencies try to balance public access on the coast with private ownership rights.

The Coastal Commission favors “managed retreat,” where nature is allowed to take its own course and increasingly consume more beach bluffs because of climate change.

According to the Coastal Commission’s latest key metrics report, the Coastal Commission approved 394 coastal development permits in 2024. Local governments, however, approved more than triple the amount—1,479 permits—last year.

TRIPLED DOWN In 2024, local governments approved nearly 1,480 coastal development applications—more than triple the number greenlit by the California Coastal Commission, which is concerned about loss of beach space and reduced public access when it comes to shoreline armoring. Credit: SCREENSHOT FROM CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION KEY METRICS REPORT 2024

TRIPLED DOWN In 2024, local governments approved nearly 1,480 coastal development applications—more than triple the number greenlit by the California Coastal Commission, which is concerned about loss of beach space and reduced public access when it comes to shoreline armoring. Credit: SCREENSHOT FROM CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION KEY METRICS REPORT 2024

In 2022, Pismo Beach residents Tony and Marilee Hyman and John Okerblom’s efforts to set up a shared seawall for their neighboring properties was met with a Coastal Commission thumbs down.

While construction of the Okerblom residence began in 2009, and finished in 2013, the Hyman residence completed construction in 1938—decades before the implementation of the Coastal Act in 1977. Marilee Hyman previously told New Times that the Coastal Commission ignored the latter fact and focused on the Okerblom house’s dates instead.

“The Hyman-Okerblom seawall was to protect a residence that was not eligible for shoreline armoring; it was built in 2013, and only ‘existing structures’ built before 1977 when the Coastal Act was enacted, coastal-dependent uses, and public beaches are eligible for shoreline armoring,” Kahn said. “The [Naomi Avenue] residence qualifies for armoring as an existing structure that was built prior to the Coastal Act.”

The Coastal Commission also issued a permit to a beachfront single-family residence in Cayucos for a 145-foot-long and 30-to-45-foot-tall seawall. They’re the only two seawalls the Coastal Commission’s approved this calendar year on the Central Coast.

The Cayucos house has been around since before the Coastal Act and hasn’t been redeveloped, according to the commission’s staff report. The commission approved its permit, saying the home’s in danger from erosion and would require hard armoring.

But the approval comes with certain conditions.

Not only must the property owners remove the armoring if the house is redeveloped, but the applicant must also collaborate with San Luis Obispo County Parks to restore and improve the storm-damaged public coastal beach accessway at Mannix Avenue. A public access easement must be recorded on the beach portion of the property, too.

Coastal Commission staff also took measures to appease the Morro Coast Audubon Society, which was concerned about the impact of the proposed seawall on birds like the black oystercatcher.

“Construction should take place outside the nesting bird season in order to prevent impacts to nesting birds,” society Conservation Committee Chair Michael Mulroy wrote to commissioners. “The seawall design should incorporate surface features such as ledges that provide nesting and roosting habitat for seabirds and shorebirds.”

Coastal Commission staff said at the Oct. 10 meeting that they’ve modified the special conditions of the permit to address potential nesting bird issues. Staff added that both the Audubon Society and the applicant agreed to the new conditions.

The Pismo Beach applicants also have extra work to do. To offset the impact of their seawall over the next 20 years, the Naomi Avenue property owners must fund public coastal access improvements within the immediate project area. One of these upgrades includes coordinating with the city of Pismo Beach to repair the Vista Del Mar stairway. The city didn’t respond to New Times’ request for comment.

“The whole purpose of this is to protect the residents from future erosion issues. So, for them [property owners], it’ll definitely be a good thing,” the Coastal Commission’s Kahn said. “I would say that for the general public, generally speaking, armoring tends to have some pretty significant impacts … loss of beach space and shoreline area … and it also introduces an unnatural element into the coastal viewshed.” ∆

Reach Staff Writer Bulbul Rajagopal at brajagopal@newtimesslo.com.

This article appears in Oct 16-26, 2025.

Related

Local News: Committed to You, Fueled by Your Support.

Local news strengthens San Luis Obispo County. Help New Times continue delivering quality journalism with a contribution to our journalism fund today.