Traveling near the Warehouse District with Derrek Miranda is akin to riding in a motorcade with an elected official.

Under the moniker Whitewallstuntz, Miranda has carved out a name for himself in downtown Los Angeles. On social media, he can be seen cutting through the most downtrodden parts of Skid Row on his white and neon green Honda Grom minibike, almost always in search of a subject to document.

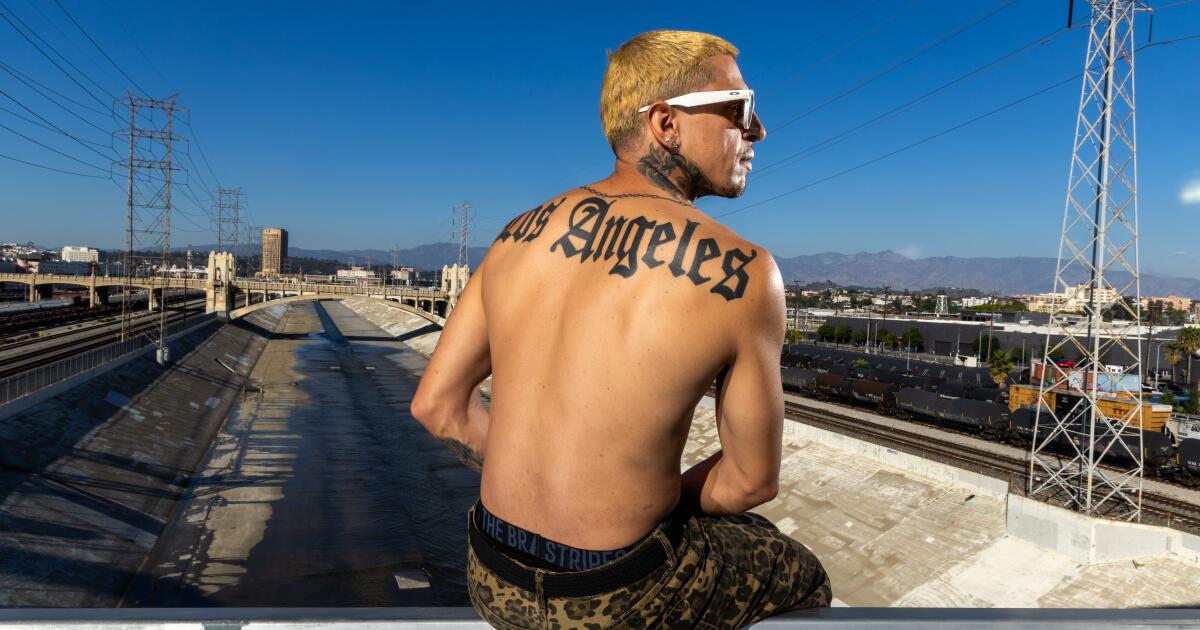

He has amassed nearly 300,000 followers across TikTok, Instagram and Facebook. He can be seen letting sparks fly from his tail scraper on the 10 Freeway with a “Los Angeles” tattoo emblazoned across his back, chopping it up with LAPD officers or, most commonly, touring homeless encampments to show, as he puts it, “what real life in L.A. is like.”

Derrek Miranda pops a wheelie on his motorbike on the 6th Street bridge in Los Angeles.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

“A lot of people are scared of these human beings because they look at them like they’re zombies or something,” Miranda said. “A lot of these people just have a story they want to tell, or they want to talk about, and not a lot of people want to hear them out.”

Miranda fashions himself equal parts good Samaritan, stuntman and documentary filmmaker. He produces his own short-form videos, feeding an internet audience hungry for unfiltered views of L.A.’s underbelly.

He is among a growing wave of influencers who create content that toes a fine line between advocacy and exploitation.

Miranda has documented a litany of drug trades in broad daylight, whooped as he recorded violent altercations between homeless individuals that he later titled “Bum Fights” and coaxed sex workers into a brief thrill by taking them on the back of his bike while popping wheelies.

But he has also engaged in thoughtful conversation with those who usually go unheard and unseen. He provides resources like clothing or food at a more intimate level than a contracted social services worker. He has personally delivered Narcan to help some recover from the brink of overdose in multiple videos.

“I want to show the reality of life, not only behind a closed door, curtains and, you know, a chandelier when you walk in,” Miranda said. “I want to show behind the tent zipper … It just shows real life, how these people still be human beings and live like an animal.”

Miranda was born in Long Beach and raised in East Compton. For years, he said, he was primarily employed as a private hibachi chef and rode bikes as a hobby. He said he was struck by a van during immigration protests in June, which put him out of work temporarily. It turned into a permanent leave after his pages started to gain traction.

Since then, he has lived in a camper van while pushing out near-daily content on his page that is occasionally licensed by mainstream TV news organizations — the bulk of his current income.

As Miranda made his rounds on a recent evening downtown, subjects of past videos on his page popped out of their sidewalk encampments to catch up.

“I’ve known him for what feels like all my life, but it’s been about three years,” said Alvin Jones, 32, who lives in an encampment on 5th Street and Stanford Avenue. “He’s telling stories about people out here, who don’t really have a shot at getting their stories heard very often.”

Although Miranda has admirers on the street, there are also detractors who believe his content can be harmful to the homeless community.

“Dont praise/normalize this kind of living,” one comment read on a video titled “Tent Tour.”

“Take this s— down why would you even record this bro,” another read on a video of Miranda in conversation with a homeless person.

Miranda recognizes the “controversial” nature of his work, but views it as an effort to be transparent about what life is like for the city’s most marginalized residents.

He is openly critical of state and city policy and said he believes more can be done by officials to ease the burden on a vulnerable homeless population.

“Most of the time they just put people into a housing complex where there’s a bunch of different people in one room,” he said. “You get a bed, but then what happens is everyone starts fighting with each other, taking stuff. It doesn’t really make anything better.”

Another account, Street People of Los Angeles, claims to have had more than 700,000 Instagram followers before being suspended by the platform. A replacement has already sprung up, with tens of thousands of people tuning in for gritty videos of squalor and street life.

One of Miranda’s close friends, Brandon Castro — who goes by Brandonexploredthis on Instagram, where he makes videos touring abandoned buildings — said Miranda’s work extends into direct advocacy for his subjects. The two once reunited a missing homeless individual with his sister in Redding after one of their joint posts went viral, Castro said.

“I think some people take it the wrong way sometimes seeing someone post another struggling, but I’ve seen it help so many people and give so much encouragement and confidence,” Castro said.

Miranda’s supporters argue his work comes from a place of compassion, in the same vein as one TikToker who surprises day laborers and street vendors with free trips to Disneyland, then posts footage of their jubilant experiences to a global audience.

Miranda said both of his parents experienced addiction, and his refuge in childhood came from riding motorcycles — a passion that has followed him into adulthood and onto his page.

After the Dodgers World Series parade downtown, he was recorded engaging in a brief takeover at the intersection of Hope and 8th streets with other motorcyclists. Standing with one foot on the right peg of his bike in a half-pirouette, Miranda mimed pumping his other foot across the pavement as if propelling a scooter. Officers arrived to disperse the crowd soon after.

LAPD officers mingle with and check in on Miranda often, he said, but some of his activities seem to run counter to the department’s years-long attempts to decrease takeover-style gatherings.

In a news conference in August, L.A. Dist. Atty. Nathan Hochman addressed a growing issue of dangerous street takeovers — usually involving cars or trucks — that he said have been “plaguing and ravaging communities for years.”

“If you engage in destructive, dangerous or ultimately deadly conduct and if you’re a promoter, don’t even think for a second you can hide anymore,” Hochman said. “We’re coming after you.”

Miranda denied that he’d put anyone in danger on his bike. He said his more rambunctious activities — including videos of stunt maneuvers on the highways that attract a healthy viewership — are simply a therapeutic means of relief from the exhaustive woes of homelessness that plague both him and his subjects.

“I feel free and at peace on the bike,” Miranda said. “It’s like I can go anywhere, like the city is a big playground for me.”