Controversial changes to Oakland’s rules governing how it manages homeless camps were tabled again on Tuesday by the Oakland City Council, after officials received a letter from a state agency that flagged problems with the proposal.

The homeless camp legislation, written by Councilmember Ken Houston, would crack down on camps, permitting the city to tow vehicles people are living in, and to clear more camps even when there’s no other shelter available.

Tuesday would have been the first time the full council took up the proposal, after a series of rescheduled and ambiguous meetings.

But at the start of the session, Council President Kevin Jenkins announced the delay, explaining that state and county funding Oakland relies on could be lost if the plan is approved in its current form.

“I think it’s imperative that we as a city keep funding,” Jenkins said.

The council chambers — packed with members of the public hoping to weigh in on the legislation — fell silent. Two councilmembers looked at each other and shrugged. Others took out their phones and dashed off texts.

The author of the proposal, Houston, appeared as surprised as anyone.

“Can you give me a reason why it’s being pulled?” he asked Jenkins.

Jenkins said the state was concerned that the policy bans homeless people from living in too many parts of the city. “We are a very urban city, so where people can go when they are unsheltered is something that we’re going to have to work on,” said Jenkins. He said the council could return to it in January.

Jenkins then assured Houston that the public could still share comments.

And weigh in the public did.

Dozens of speakers lined up in person and on Zoom, almost everyone criticizing the policy and imploring the council to “start from scratch.”

“I wish you guys wouldn’t think we’re criminals,” said an unhoused woman who goes by Alley Cat. Raised in Oakland, she said she works two jobs but still hasn’t been able to afford more than an RV to live in since she lost her housing.

“I run from the city of Oakland in my RV so they don’t destroy it,” she said, tearing up. “We don’t even know we can speak at these things — you don’t reach out to us.”

State leaders say concerns they raised months ago remain the same

On Monday, the California Interagency Council on Homelessness’ Executive Director Meghan Marshall wrote to the city administrator and other officials, expressing concerns with Houston’s encampment proposal. Her organization did the same in August.

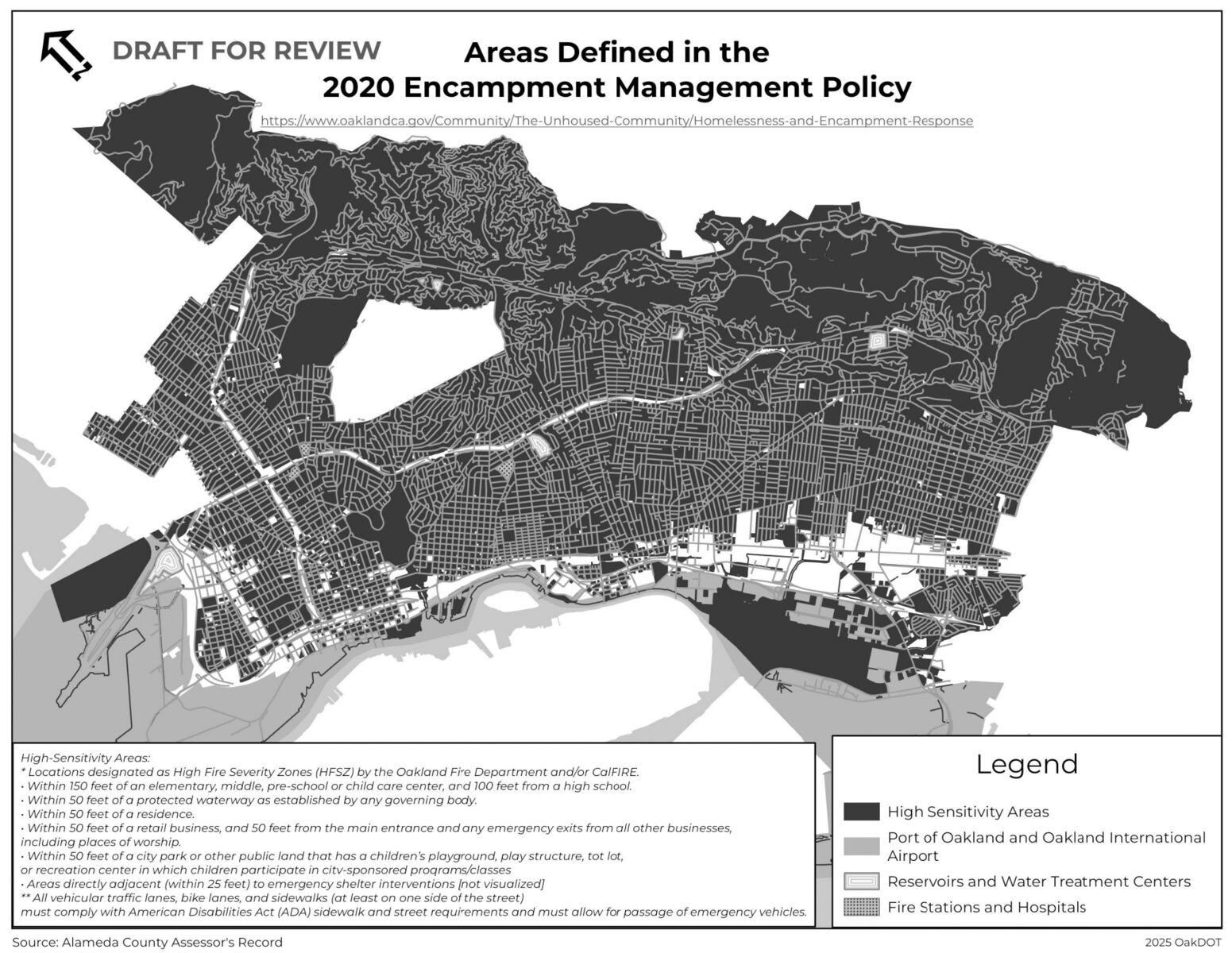

The feedback, which City Administrator Jestin Johnson shared with the council on Monday over email, centered on the designation, in Houston’s proposal, of “high-sensitivity” and “low-sensitivity” zones in Oakland. A carryover from the city’s current encampment policy, these designations determine which areas the city will target for homeless camp closures or leave alone.

“The definition of ‘high-sensitivity areas’ is still so broad, that, in practice, it appears to classify nearly the entire city as high-sensitivity,” Marshall wrote in her email, which was shared with The Oaklandside by the city. “As written, it is difficult to determine where Oaklanders experiencing homelessness can exist in the City without being subject to enforcement under this policy.”

Because of this, Marshall said, “we cannot assess how the policy…aligns with State funding requirements.”

A map attached to Houston’s proposal does, in fact, label almost all of Oakland — save for small areas of the East Oakland and West Oakland flats — “high-sensitivity,” or subject to more aggressive closures of camps.

Most of the city — colored black on this map — would be considered “high-sensitivity,” or off-limits for encampments, under Councilmember Ken Houston’s plan. The state raised concerns about the minimal permitted areas (in white). Credit: City of Oakland

Most of the city — colored black on this map — would be considered “high-sensitivity,” or off-limits for encampments, under Councilmember Ken Houston’s plan. The state raised concerns about the minimal permitted areas (in white). Credit: City of Oakland

This is not new in Houston’s proposal. The city’s existing rules do the same — and have long received criticism for this from homeless people and advocates. The difference is that the current policy still prevents closures in high-sensitivity zones if there’s no other shelter available for the residents to move to. Houston’s plan would still instruct the city to offer shelter, but not make it a requirement before closure.

Under Houston’s changes, the city administration would come back to the council within 90 days, proposing city property that could be converted into shelter or additional low-sensitivity zones.

Houston took out some of the bite — but not all — from his new rules

When Houston and his co-author, Jenkin’s chief of staff Patricia Brooks, first introduced their ideas for changing Oakland’s approach to homelessness in September, they drew heavy attention. Over the course of a seven-hour council committee meeting that month, dozens of community members excoriated Houston and his supporters for “criminalizing” homeless people, and several councilmembers also grilled him about his plan, skeptical of its impacts.

A number of other people, though, came to the meeting to thank Houston and Brooks for taking a significant swing at the crisis.

That meeting ended in ambiguity, with several councilmembers telling Houston they’d only support his plan with major amendments.

This week, Houston returned with an updated policy. It appears that he and Brooks made an effort to tone down some of the more controversial language while maintaining the meat of the proposal.

A speaker dressed as Batman was among dozens of community members who criticized Houston’s encampment plan Tuesday. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

A speaker dressed as Batman was among dozens of community members who criticized Houston’s encampment plan Tuesday. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

Houston’s previous plan undid the key city requirement to offer shelter to all residents of an encampment before it’s shut down. For years, that has meant the city cannot close a camp if there are no beds available for the people living there.

The updated proposal still removes the shelter requirement. However, it now encourages the city to try to find alternative homes for people in camps.

Generally, Oakland will “make every reasonable effort to provide offers to all affected” residents, or let them move to a low-sensitivity location if no shelter is available, it says. It spells out the process for identifying and offering shelter spots.

However, in cases where closures are prompted by “urgent health and safety conditions,” or because of “reencampment” after a closure, there are no such requirements. “Depending on the situation, such efforts may not be feasible, and in no case will emergency or urgent closures be delayed for shelter unavailability,” Houston’s new rules say.

The new proposal keeps another core piece of Oakland’s current encampment policy, which says, “The city will not cite or arrest any individual solely for camping, or otherwise for the status of being homeless.” In September, Houston had proposed striking this prohibition, allowing arrests of campers, but he’s now walked that back.

As was the case in September, Houston’s latest proposal excludes vehicle homes from the definition of homelessness. That means the city would have more leeway to tow RV encampments and car dwellings than to remove tent communities. The new policy says those city workers “should consider” calling the encampment team to come offer the person living in a vehicle some other type of shelter before towing, but it doesn’t require it.

This change could have significant impacts; the population living in vehicles in Oakland has steadily increased in recent years, currently making up over half of the city’s unsheltered residents.

A final noteworthy change is more semantic than substantial.

In September, Houston wanted to rename the city’s Encampment Management Policy to the Encampment Abatement Policy. This change — seemingly made because the new rules focus more on eliminating encampments — resulted in an awkward acronym for the group of city workers handling homelessness: the Encampment Abatement Team, or EAT.

Now, Houston’s proposing fusing the two to adopt an “Encampment Management and Abatement Policy.”

After the meeting, Houston took to Instagram, saying he wasn’t deterred by the negative comments from the public and planned to bring back the policy in January.

“That was not even a battle! That was a walk in the park,” he said.

“*” indicates required fields