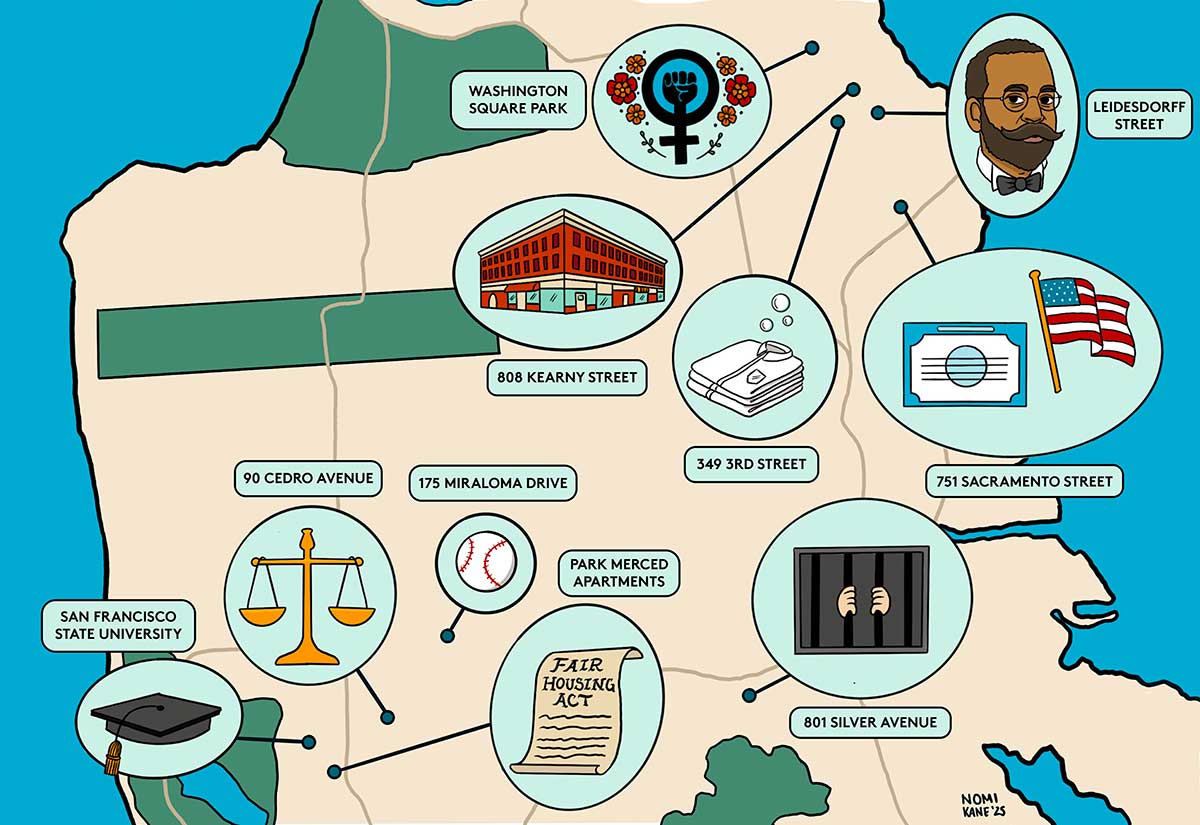

Inside the classroom is not the only or the best place for San Francisco residents of all ages to learn about discrimination and the ongoing struggles for equality and justice. Not enough native-born San Franciscans and people attracted to the city from other parts of the nation or the world have been introduced to the places that represent past discrimination and the historic and courageous efforts to overcome them. A trip across San Francisco reveals the obstacles faced, challenges addressed, and progress made by people from all backgrounds in recognizing and remedying discrimination and injustices, and in contributing to the city’s overall success.

Here is my top 10 list of San Francisco places and their significance to civil rights. Others will have their own places to add and communities to include. Each has a message — sometimes forgotten, sometimes never told — about where we have come from as San Franciscans.

– San Francisco State University. Establishing a formal college of ethnic studies was a key demand of student demonstrators at San Francisco State in 1968. The success of the multicultural leaders representing Black, Latino, Native American, and Asian American students and communities eventually led to ethnic studies programs in over 400 colleges and universities nationwide.

– Parkmerced Apartments. Next to the San Francisco State campus, the Parkmerced Apartments were the subject of the first case involving the 1968 Fair Housing Act to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Paul Trafficante established that Parkmerced’s rental policies not only discriminated against African Americans but also denied white families the benefits of an integrated community.

– 90 Cedro Avenue. In nearby Ingleside Terraces, this address was the home of Cecil Poole, the nation’s first African American U.S. Attorney. He was appointed to that post by President Kennedy in 1961 and later appointed as a federal judge by President Ford in 1976 and to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals by President Carter. In 1957, the Poole Family was subjected to a cross burning on their lawn by two nearby teenagers.

– 175 Miraloma Drive. When the Giants moved west from New York after the 1957 baseball season, Willie Mays found a home to buy on Miraloma Drive. The sale was delayed when the owner, a home builder, became reluctant out of fear that others in his industry would deny him future work for selling to an African American family. The sale went through after nationwide criticism that San Francisco was proving itself not ready to be considered a major league city, and a demand by Mayor George Christopher that the owner sell him the house so he could sell it to Willie Mays. In this same era, Asian Americans were forced to find proxy home buyers to get around racially restrictive covenants that made selling to them unlawful.

– 801 Silver Avenue. During World War II, 801 Silver Avenue was used as an immigration detention center for Japanese, Italian, and German immigrants and some U.S. citizens of those ancestries who were considered “enemy aliens” under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Families were later moved to San Francisco-owned land at Sharp Park in Pacifica. Other Japanese Americans were relocated to the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno and more distant camps throughout the country.

– Washington Square. A historic state landmark here designates the home of Juana Briones, one of California’s first women landowners and a remarkable San Francisco businesswoman in the last half of the 19th century. She arrived here in the 1820s, has been called “San Francisco’s Founding Mother” and overcame obstacles for women and Latino Californians for success in traditional medicine as well as farming.

– 751 Sacramento Street. Wong Kim Ark was born at this location in 1873 but was denied entry to the United States following a trip to China in 1894. The Chinese Six Companies hired a legal team and took the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. His victory established the birthright citizenship principle, interpreting the first section of the 14th Amendment that has benefitted millions of children born in the United States to a parent or parents who are not yet United States citizens themselves. The Wong Kim Ark rule: “If you’re born here, you’re a United States citizen.”

– Leidesdorff Street. The short Financial District street is emblematic of the relatively short life of William Leidesdorff whose impact was felt locally, nationally, and internationally. Even prior to California statehood, he started San Francisco’s first hotel and was one of the nation’s first Black millionaires. His civic duty spanned from chairing the first San Francisco school board to being United States vice consul to Mexico.

– 808 Kearny Street. Now the site of City College’s Chinatown campus, 808 Kearny Street was the site of the International Hotel, which for decades in the early to mid-1900s was a center of San Francisco’s manong society of unmarried Filipino immigrant men who toiled in service occupations in San Francisco as well as in agriculture and fishing on the West Coast from Southern California to Alaska. An important cultural and political center, the International Hotel survived until the 1970s when it was shut down only after vehement community protests and the arrest of Sheriff Richard Hongisto, who initially refused to carry out the court-ordered eviction of elderly residents.

– 349 Third Street. In 1886, the Chinese laundry at this address was the subject of a major United States Supreme Court decision on civil rights, which is relied upon to this day by Black, Latino, women, and other advocates challenging laws that may be written in neutral language but are discriminatorily applied. The laundry owner, Lee Yick, was charged with a misdemeanor for operating the establishment after being denied a license by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. All but one white applicant had been approved, while all Chinese applicants were denied. The foundational principle of the Constitution outlawing such discrimination came to life here.

San Francisco stands with Philadelphia, Selma, Topeka, Delano and other cities as places where discrimination deprived people of their basic civil rights and where people of all backgrounds supported the vindication of those rights. Our neighborhoods provide the real lessons of ethnic studies and shared values overcoming discrimination.

Related