This article was originally published by the nonprofit newsroom EdSource.

A $4 billion-a-year initiative created to combat pandemic-related learning loss and expand the regular school day in California is also addressing another issue — recruiting teachers.

The Expanded Learning Opportunities Program championed by Gov. Gavin Newsom — and on which the state has spent a total of about $18 billion so far — supports an array of summer enrichment programs and after-school programs. They are typically run by nonprofit organizations on school sites in partnership with local school districts.

Education leaders interviewed by EdSource say it is helping to address one of the most critical challenges facing California’s public schools: a persistent shortage of fully credentialed teachers, especially in high-demand areas such as math, special education and bilingual education.

“While it was not an intention in the design of the program, it offers a great teacher recruitment opportunity,” said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the State Board of Education, who worked closely with Newsom in designing the initiative.

California does not track the total annual demand for fully credentialed teachers. One indication of the need is that about 32,000 teachers out of nearly 270,000 in California were teaching with temporary, emergency or short-term credentials of some kind in 2022-23, the latest year for which figures are available, according to calculations by the Learning Policy Institute.

Leaders of nonprofit summer programs, such as Aim High and Freedom School, point to numerous former or current students and staff members who have gone into teaching or are considering doing so.

Aim High, which offers a five-week summer program for fifth to eighth graders in 17 sites in the Bay Area, estimates that in its 40-year history, it has helped bring thousands of teachers into the profession. Of its staff this summer, over 100 are either considering or actively pursuing careers in education, said CEO Jesús Galindo, underscoring its potential, along with other expanded learning programs, to reduce California’s teacher shortages.

Aiming for a teaching credential

Nuntehui Espinoza, 27, an Aim High staffer over the summer, is a student teacher at Urban Promise Academy, a small Oakland public school serving sixth to eighth graders — a school she once attended as a student.

It was then that she first participated in Aim High’s summer program, which offers a mix of rigorous academic instruction and fun activities, including cooking, drama, basketball and Ultimate Frisbee.

Later, as an undergraduate at the University of California, Merced, Espinoza got a summer job with Aim High as a teaching assistant in math. In the summer, she became the lead teacher in its “Issues and Choices” class that focuses on topics ranging from bullying and media literacy to the impact of stress on the brain and career exploration.

Her work at Aim High “heavily inspired her to become a teacher,” she said. She recalls receiving a card at the end of the summer from an Aim High student who was still learning English. “He ended up thanking me for what he had learned,” she said, which for her underscored the impact she could have. “It was super emotional for me.”

Now, she is on the verge of earning a teaching credential and a master’s degree from the Berkeley Teacher Education Program at UC Berkeley.

Aim High has made nurturing and supporting prospective teachers central to its mission, including through its year-round Aspiring Teacher Fellowship program. Its programs are underwritten partly with state funding, including funding from the Oakland Unified School District and the West Contra Costa Unified School District.

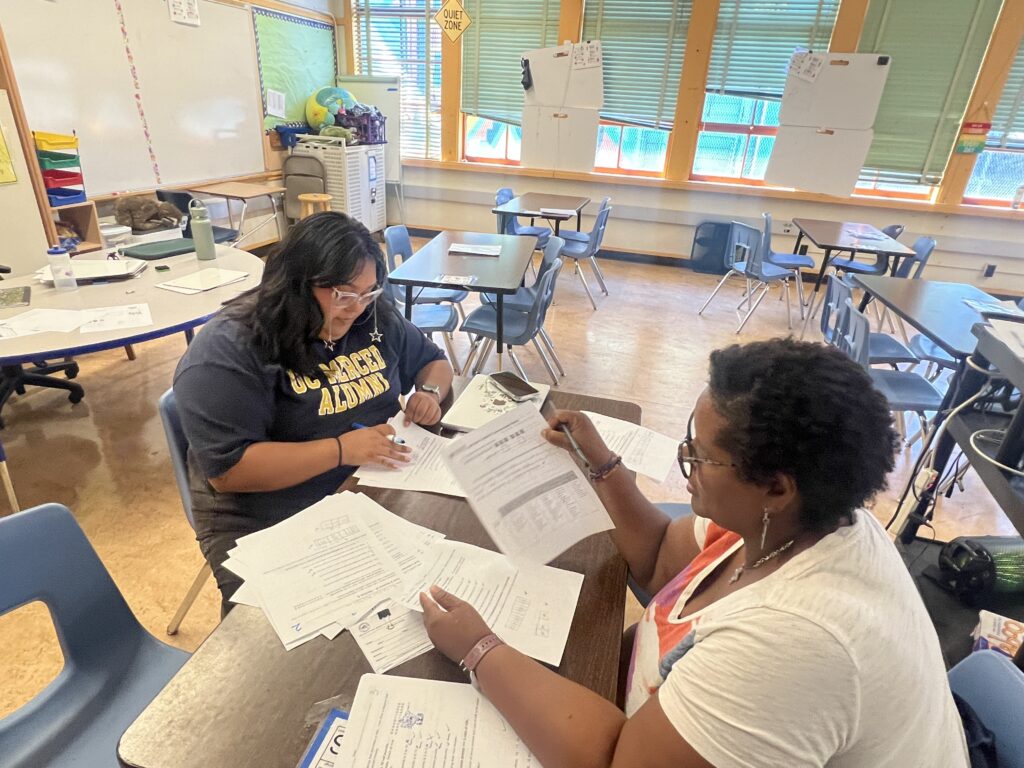

Back at her old school in Oakland, Espinoza works under the guidance of Ann-Marie Gamble, a veteran math teacher of 26 years. On a recent morning during their daily preparation period, the two reviewed a math quiz on ratios they had just administered to their students.

Despite being vastly more experienced, Gamble said she often turns to Espinoza for advice. “Every day I am asking her, as a former student at the school and someone who is closer in age to my students, what can I do better?” she said. “It’s a nice symbiotic relationship.”

A teaching credential is not required to work in summer and after-school programs. Class sizes are usually small, which also makes the experience less daunting. Jobs tend to be part time, and participants are not just thrown into the deep end but typically get support on how to work well with kids.

They even offer opportunities for high school students to participate as paid interns, some of whom are then inspired to pursue teaching careers, according to a recent report by the Partnership for Children & Youth, a nonprofit organization that works with school districts around the state to launch expanded learning programs.

Nurturing new teachers in West Contra Costa

West Contra Costa Unified Superintendent Cheryl Cotton said her 25,000-student district, which includes Richmond and a handful of other East Bay communities, has several initiatives underway to nurture new teachers. But, she said, the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program has emerged as a key source. Staff who work there bring strengths that have the potential to make them especially effective teachers, she says.

“In general, our after-school staff are local community residents who come to our classrooms with skill sets in lesson planning, classroom management and supporting students,” she said. “More importantly, they have an interest in and love for engaging with students.”

Leslie Jauregui, who has lived in the district since third grade and graduated from its public schools, fits that profile. She had long considered a career in teaching. But she was put off by the hurdles just to get into a credentialing program, like the CBEST exam. “I was scared of all those tests,” she said.Credit: Louis Freedberg / EdSource

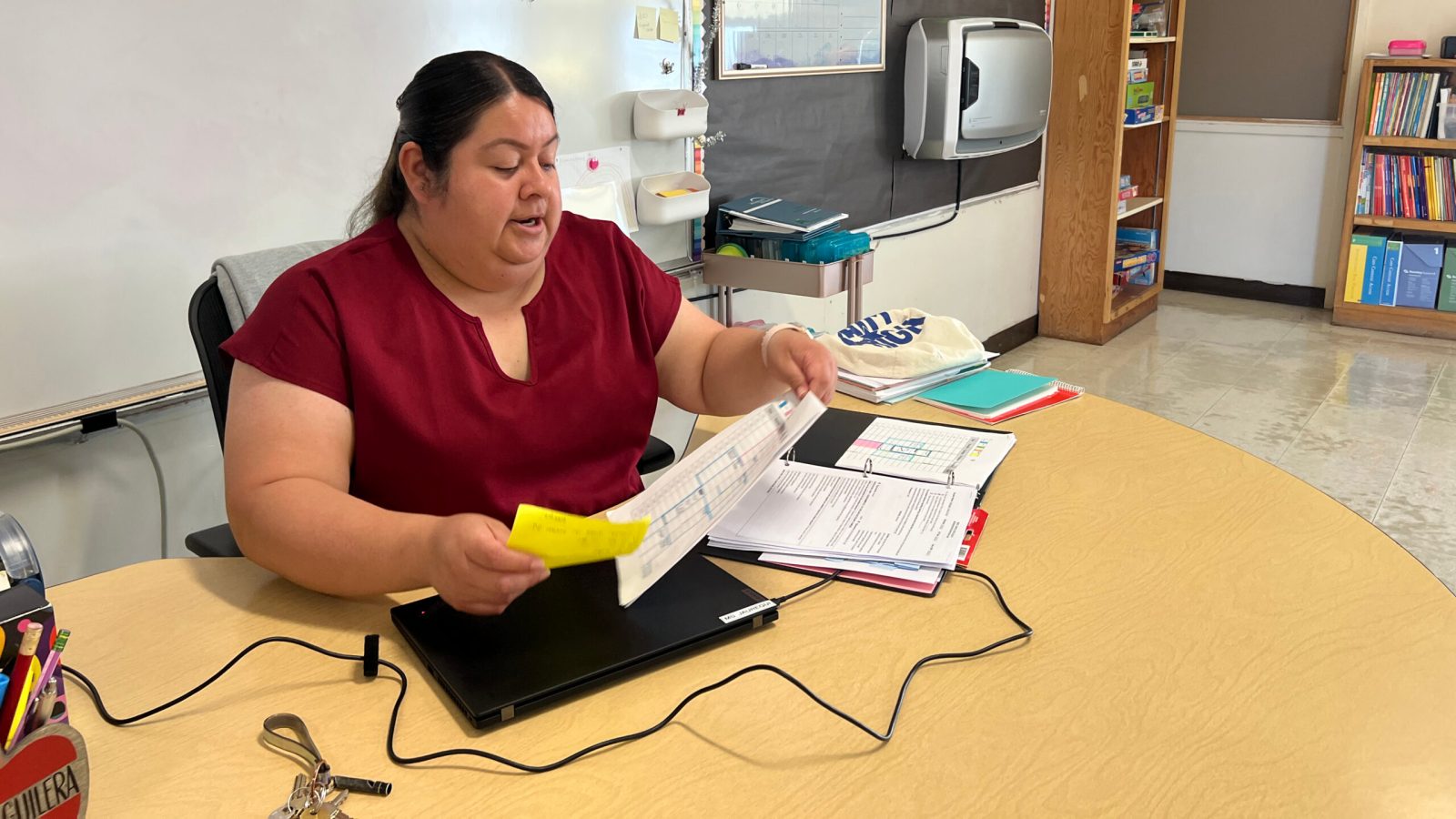

Leslie Jauregui in her classroom at Highland Elementary in Richmond. Credit: Louis Freedberg/EdSource

Leslie Jauregui in her classroom at Highland Elementary in Richmond. Credit: Louis Freedberg/EdSource

She began working at West Contra Costa Unified as a special education teaching assistant. In 2018, she was hired as the campus coordinator for Aim High when it opened in Richmond. She realized that with the support offered to teachers there, she too could be successful as a teacher.

“I really wanted to be a teacher, but Aim High convinced me that I could be one,” she said. She later enrolled in the Teacher Residency Program jointly sponsored by her district and California State University, East Bay, and received her in-demand special education credential.

Today, Jauregui is a full-time special education teacher at Highland Elementary School in Richmond while continuing as co-site director of Aim High during the summer.

Other summer programs have had a similar impact on students’ career choices. Michael-Sesen Perrilliat, 31, had worked for years as an education policy analyst for EdTrust West, an Oakland-based research and advocacy organization. He was considering going to law school but was also interested in working more closely with children.

This past summer, he signed up to work at the Freedom School in Richmond, a summer program operated under the umbrella of the Children’s Defense Fund. It offers intensive reading and vocabulary building through an African American history lens, as well as after-school activities like skateboarding, robotics, mural painting and African dance.

Being in the classroom was “a totally transformational experience,” he said. “Just seeing how the kids grew throughout the summer was hugely enriching” — far more than the policy work he had been doing. He is considering pursuing a master’s degree in social work that would allow him to work as a counselor or in other related positions in schools or community colleges. For now, he is leaning toward getting his teaching credential first.

Cortney Walker, a Richmond native and Freedom School staffer, represents the next generation of teachers California will need. Although only 20, she was a site coordinator this summer in Richmond. She’s currently a junior at California State University, Northridge, majoring in child and adolescent development, and is planning to get a teaching credential when she graduates.

The previous two summers, she taught small student groups at the Freedom School. “It opened my eyes to what being a teacher is going to look like,” she said, including basics like decorating her classroom, preparing worksheets and developing a curriculum. “It was exactly the experience I was looking for.”

Her long-term dream is to open her own day care center. But one thing she is sure of: “I’m young, I haven’t had the burnout like many teachers are experiencing right now. I’m ready to take on the world.”

“*” indicates required fields