Public trust in Oakland’s leadership hit a nadir last year.

Residents had seen crime rates shoot up, federal agents raid the mayor’s house, voters recall said mayor, and the city plunge into a financial crisis. It’s no wonder that a city budget survey found in 2024 that “satisfaction with local government is at a record low.”

At all levels of government, there are laws designed to build public trust by providing transparency into what powerful officials are doing and saying, so residents and taxpayers can hold them to account and weigh in. One such law is the California Public Records Act. This act was modeled on a federal law you may have heard of called the Freedom of Information Act.

Enacted in 1968, the state law established a “fundamental and necessary right” to access state and local government records. The law says that all government records are open to the public unless it provides an eligible reason — an “exemption” — for why a particular record can be kept secret. And the law spells out exactly what government officials need to do when they get a public records request: promptly search for and hand over records.

Requesting public records in Oakland

Any member of the public — not just journalists — can file a records request in Oakland, through the city’s online portal. You can track the city’s progress and responses to your requests on the portal, and view other people’s requests and records, too.

Elected officials in Oakland know all of this, because they and their staff are trained in the California Public Records Act when they enter office, according to the city. Each councilmember has staff members who typically assist with records requests. They also have access to the City Attorney’s Office, a spokesperson told us, where they can ask questions about compliance with tricky requests.

But The Oaklandside has found most of them regularly flout their obligations under the law, either replying to requests weeks or months after the legal deadline, providing incomplete responses, or ignoring requests altogether.

Longstanding Councilmember Noel Gallo stands out: he has illegally ignored almost all of the 14 requests we’ve filed with his office.

We reviewed 179 records requests submitted by our news organization to elected officials across the city since 2023. What we found is a generally abysmal response rate. With the exception of the Oakland City Attorney’s office, nearly all officials and their staff consistently failed to comply with the law, but a couple of them, including Gallo, have particularly egregious records. For this story, we focused on 91 requests to the current sitting councilmembers, since they’re among the most powerful elected officials in Oakland’s government. The Oaklandside also files requests with city departments but we’re not addressing those in this article.

Sam Ferguson, an East Bay attorney who specializes in suing government agencies for failing to comply with public records laws, told The Oaklandside that the Oakland City Council’s track record is not in compliance with the law. (Ferguson represented a group of journalists who sued the Oakland Police Department for failing to comply with public records law. In 2021, the city agreed to settle the case by clearing its backlog of records requests. Ferguson also represented The Oaklandside news editor Darwin BondGraham in a different lawsuit.)

“It is sad to see Oakland’s leaders undermining transparency. Our elected leaders set the tone for the city,” said Ferguson. “Why should we expect city agencies to facilitate public access when those at the top fail to do so?”

Only 39% of our records requests to councilmembers have been fulfilled

Multiple councilmembers have not responded to our requests for communications about a contentious Gaza ceasefire resolution in 2023. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

Multiple councilmembers have not responded to our requests for communications about a contentious Gaza ceasefire resolution in 2023. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

The Public Records Act broadly defines public records as “Any writing containing information relating to the conduct of the public’s business prepared, owned, used, or retained by any state or local agency regardless of physical form or characteristics.”

The law goes further, making clear that “writing” actually means every possible form of communication or representation, “including letters, words, pictures, sounds, or symbols, or combinations thereof, and any record thereby created, regardless of the manner in which the record has been stored.” That means datasets, videos, audio files, and all sorts of other stuff are included in the definition of what a public record is. The law also applies to personal devices used by officials for city business.

When they receive a public records request, officials, including elected leaders and government employees, must respond within 10 calendar days to let the requester know whether the records exist, although they can request a 14-day extension.

The law doesn’t require officials to produce records within a certain timeframe, just that they do so “promptly.”

We wanted to determine if Oakland’s elected officials – and specifically current members of the city council – are following the law. There are some limits to our findings. Our story only covers public records requests filed by reporters who work for The Oaklandside; we did not include requests filed by other newsrooms or members of the public. We didn’t file an equal number of CPRA requests with each elected official, and our total tally includes some councilmembers who are no longer in office.

What we can say with confidence is that almost every official who has gotten at least one public records request from us is failing to follow the law.

We’ve filed 91 public records requests with current members of the Oakland City Council. In only 13 of those cases did an official let us know within the legally mandated 10-day period whether or not they had records. And as of early September, when we first reached out to councilmembers for this story, they had only completed 36 of our requests — roughly 39%. The most recent request in our analysis is five weeks overdue, and many have been languishing for months or even years.

In some cases councilmembers turned over records that weren’t usable. For example, one councilmember shared a copy of their monthly calendar but as a single screenshot, which prevented us from seeing their individual daily meetings. In other cases councilmembers notified us they were withholding records that we later determined they possessed. And in others, councilmembers partially complied by providing some records and are still in the process of turning over more. For the purpose of this story, we did not count these records as “complete.”

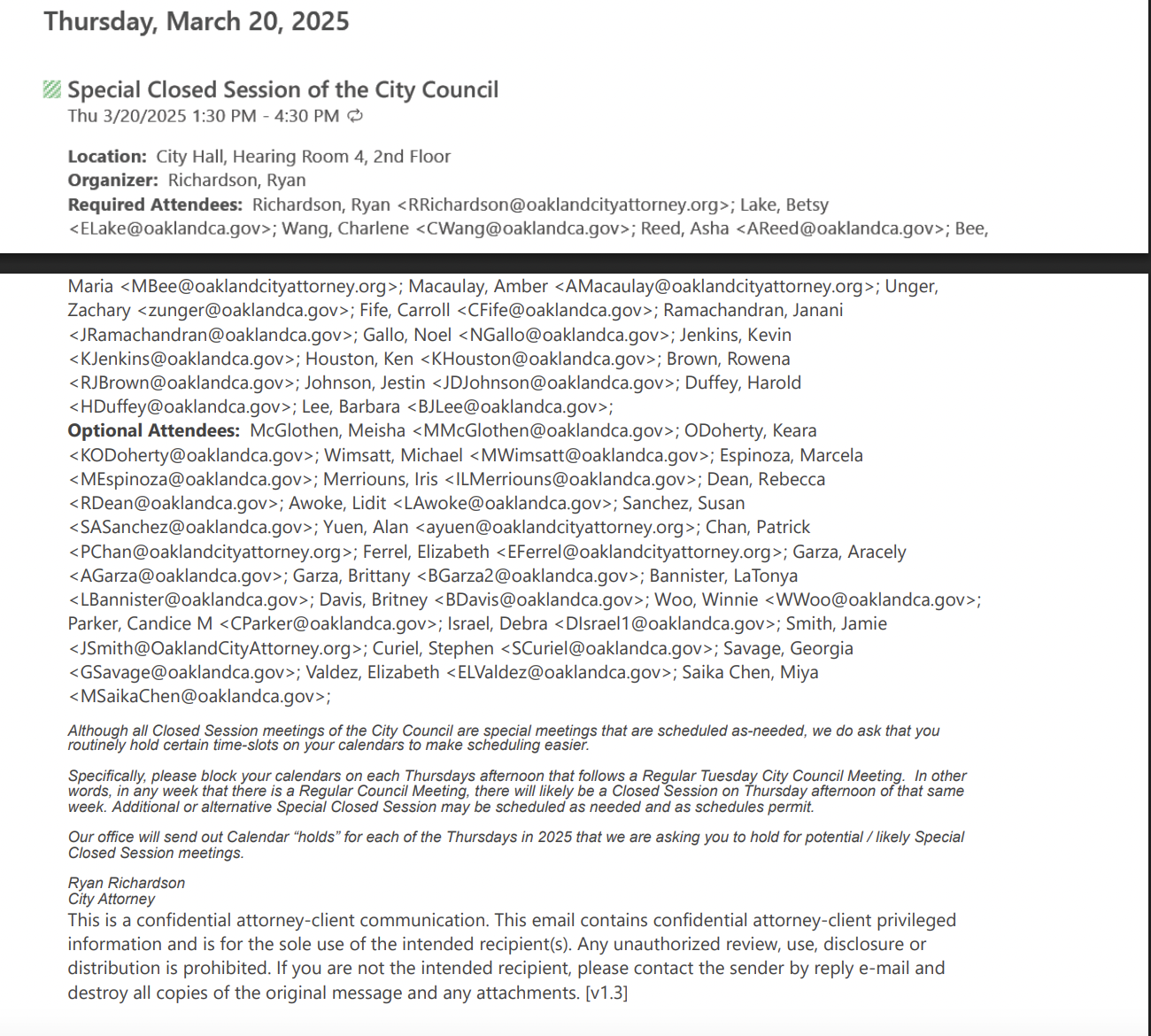

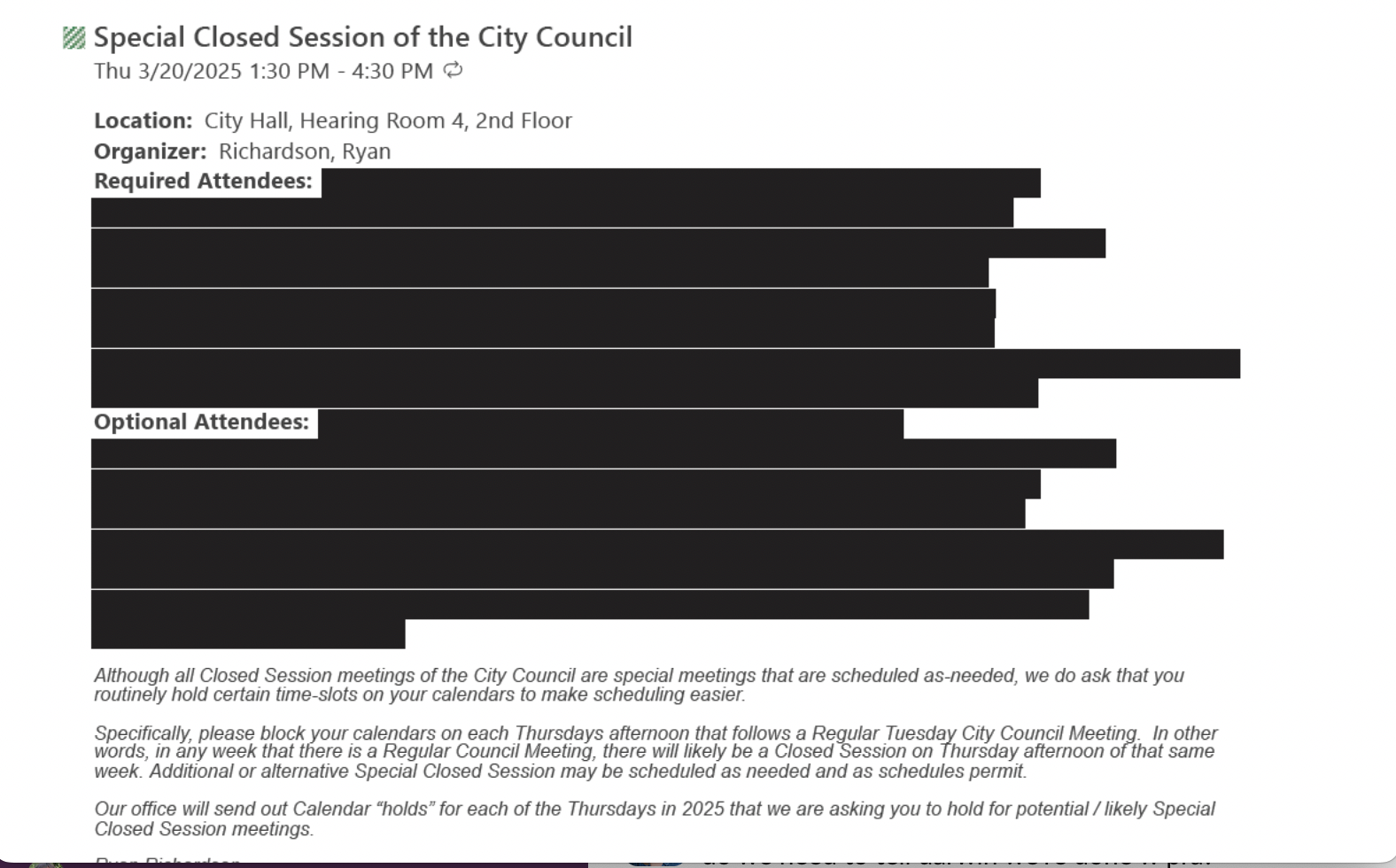

When councilmembers responded to our requests, they often interpreted the law’s exemptions very differently. The law allows government officials to redact — blackout — information in a record that doesn’t have to be released. This can include private phone numbers, emails, or other sensitive information. Oakland’s city leaders were inconsistent about what they chose to redact.

For example, councilmembers Charlene Wang and Rowena Brown each provided us the same record of an email invitation to a closed City Council meeting in response to requests we made to both offices. Wang provided the whole invitation, while Brown redacted the names and email addresses of every invitee, essentially sending us a chunk of black ink.

An email provided by Councilmember Charlene Wang in response to a request. Credit: City of Oakland (screenshot)

An email provided by Councilmember Charlene Wang in response to a request. Credit: City of Oakland (screenshot)

The same email, redacted, provided by Councilmember Rowena Brown. Credit: City of Oakland (screenshot)

The same email, redacted, provided by Councilmember Rowena Brown. Credit: City of Oakland (screenshot)

One record we frequently ask councilmembers for is their calendar of appointments. This gives us a clear picture of who elected officials are spending time with, and what kind of work they’re doing for constituents. We’ve used those records to write stories about policies that might be on the horizon. Some councilmembers have never given us a copy of their calendar, including Gallo and former Councilmember Treva Reid. Others have turned over schedules in a format that cuts off significant amounts of text, making it impossible to tell who was at a meeting or what was being discussed.

The city attorney, who is also an elected official, has a significantly better response rate than the councilmembers. Of the 39 requests we filed with the city attorney since 2023, 24 led to a response within 10 or fewer days. Overall, the City Attorney’s Office completed 38 of our public records requests and partially completed one.

We contacted each current councilmember and requested interviews with them for this story. We also sent them links to the outstanding requests we have with their offices and asked them to explain why they haven’t fulfilled them yet.

Several of them didn’t respond, but some began fulfilling requests shortly after we reached out to them. Councilmember Carroll Fife — whose spokesperson said she was “not available” for the request and then did not respond to multiple follow-ups — later posted a video on Instagram where she explained to constituents and the press how her office handles public records requests. We found that some newer councilmembers, such as Zac Unger, have been diligent about completing public records requests. Other legislators who have been on the council longer have much spottier track records.

Councilmember Noel Gallo, right, has the worst track record when it comes to responding to our public record requests. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Councilmember Noel Gallo, right, has the worst track record when it comes to responding to our public record requests. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Oakland’s longest serving councilmember, Noel Gallo, virtually never responds to public records requests

Noel Gallo was elected in 2012, making him the longest-serving member of the Oakland City Council. Gallo has served as the chair of various council subcommittees, and earlier this year his colleagues voted for him to serve temporarily as the council president, which gave him the power to schedule legislation and run meetings.

The Oaklandside has filed 14 public records requests with Gallo since 2023. The councilmember only responded to two. Even in those cases, Gallo did not respond within the legally required 10 days.

Here are some of the records we’ve asked for that Gallo never provided:

A copy of his calendar

Communications he received before and after a council vote on a hotly debated resolution in support of a Gaza ceasefire

His communications with lobbyists for the recycling company Argent Materials, which had reported to the city that they were in contact with Gallo’s office

Communications related to a council resolution regarding PG&E

Communications regarding security companies bidding on a city contract

Gallo did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

Council President Kevin Jenkins didn’t provide records we believe he has

Council President Kevin Jenkins, right, has several pending requests from us. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Council President Kevin Jenkins, right, has several pending requests from us. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Kevin Jenkins is Oakland’s council president and earlier this year served as interim mayor. We have filed 25 public records requests with Jenkins, many of them this year because we wanted to learn about his activities as the head of the city.

To date, Jenkins has completed six of these requests. He has ignored the majority we filed between 2023 and 2025. These include requests asking for:

His communications with lobbyists for Northeastern University about a private police force

Communications with constituents about proposed changes to OPD’s vehicle pursuit policy

Text messages with San Francisco Mayor Daniel Lurie

Earlier this year, Jenkins told an Oaklandside reporter that he has text messages from community members describing what they see as disparate and unfair coverage by The Oaklandside of Black officials and leaders. After hearing this, we filed a public records request for the text messages.

In a phone call two weeks later, Jenkins told the reporter he wasn’t ignoring the request, but said he wasn’t sure they were public records. He never ended up turning over the records or citing a legal exemption for why he couldn’t.

In another case, Jenkins claimed he didn’t have records that we later confirmed were in his possession. On April 30, we filed a request for Jenkins’ communications with lobbyists for Airbnb. The company’s lobbyists reported earlier this year that they had contact with Jenkins to discuss short-term rental policies and partnering with local organizations to support the arts, housing, and special events.

A Jenkins staffer handling the request responded on June 30 claiming there were “no records responsive to this request.”

However, later, we found on the city’s records portal that a different person had requested communication records from Jenkins’ mayoral office while he was in that role. We were able to review the records Jenkins produced in response to this request, and we found within those files multiple emails between Airbnb lobbyists and Jenkins. (We also found that one of those lobbyists solicited campaign contributions from Airbnb for Jenkins. Jenkins told us he was unaware of this effort and a contribution was never made.)

On April 17, we filed a request asking Jenkins for any direct messages he sent or received through his social media accounts, including X. On June 30, Jenkins’ office responded, claiming he had no records. However, we independently obtained records of Jenkins communicating with a local political activist through direct messages on his X account during the time period covered by our request.

Jenkins declined multiple times to be interviewed for this story. But Jenkins’ chief of staff, Patricia Brooks, told The Oaklandside that some of the requests we filed with her boss were delayed due to a combination of technical and communication issues with the city’s IT Department. IT helps process many of the requests that involve searching electronic records, such as emails.

Brooks also noted that the District 6 office was not responsible for the requests we filed when Jenkins was interim mayor between January and May. Those requests would have been handled by staff in the mayor’s office.

Some of these requests took a tortured path between the two offices.

For example, on March 20 The Oaklandside filed a request for records of text messages between Jenkins and San Francisco Mayor Daniel Lurie. The request was assigned to a staffer in the mayor’s office who never told us whether any responsive records had been located.

According to Brooks, the request was then moved to the District 6 office on June 30, roughly a month after Jenkins returned to his role on the city council. Employee turnover in the district office resulted in the request not being addressed for several more weeks. Brooks said she became aware of the request after the IT Department notified her that it was overdue. After gaining authority over the request, Brooks reassigned it on September 17 to go back to the mayor’s office. To date, this request has not been completed.

Other councilmembers have mixed records

We’ve requested records on Oakland security contractors from several councilmembers. Only some have complied. Credit: Darwin BondGraham/The Oaklandside

We’ve requested records on Oakland security contractors from several councilmembers. Only some have complied. Credit: Darwin BondGraham/The Oaklandside

Zac Unger, who represents District 1, had the sole perfect track record — but he only entered office this year and we’ve only requested records from him four times.

Unger told us he has a staffer who jumps on requests as they come in.

“He knows my philosophy is I want to respond to them as quickly as possible,” he said.

Unger called the Public Records Act a “well-intentioned act with some unintended consequences that make life difficult.”

Unger recalled a time when someone sought every email their office had received that included the word “fire.”

“I had just taken office, and every email was, ‘Hey, I used to be a firefighter too.’” (Unger was an Oakland firefighter prior to his election.) “It takes us an enormous amount of time to go through and redact; you have to go through thousands and thousands of emails to make sure you’re not sending out privileged information.”

But, he said, “it’s not for me to say what’s legitimate or not. The law is the law.”

The law, as it has been interpreted by courts, does allow officials to deny a records request if it is “unduly burdensome” and “overbroad.”

District 7 Councilmember Ken Houston was elected at the same time as Unger, in November 2024. When we reached out to Houston in September, he had completed five of the seven requests we filed with his office. In the last three months he’s completed the other two.

Houston said he appreciates the California Public Records Act and made use of the law himself before he was part of the government.

“The public should have clarity on what you’re doing,” Houston said. “But a little more time would be appreciated.”

As a new official, “you get bombarded” with emails and requests, he explained. “When they see you making moves and getting things done, you get more.” It takes longer than people think to go through the records and redact private information, he said.

His office has a daily morning meeting, where they discuss requests that have come in and divide the labor. Houston recently hired a new staffer who will be able to work through them more quickly, he said.

Charlene Wang, the council’s newest member, was elected in April. We have filed five records requests with her office. When we reached out to Wang in early September, she had partially completed one request. In the weeks following, Wang completed a second request. Wang has not yet completed the following requests, which were filed in July.

In one request for communications with PG&E lobbyists, Wang responded saying no records exist, but we believe they do based on records we obtained from a different councilmember.

In a brief interview, Wang said a staffer in her office only recently received training to handle public records requests. She emphasized that records requests can be time- and resource-intensive.

A representative for Fife told us she was not available for an interview. A week later, Fife uploaded a video on Instagram where she explained the Public Records Act and how her office handles requests.

While stressing that she is committed to transparency, Fife explained in the video that she doesn’t have a dedicated staff person to handle requests, and that it would be helpful if the city provided more legal and administrative support. Given the other pressing issues in her district like homelessness and public safety, Fife said public records requests can sometimes be “cumbersome” and “a huge administrative burden.”

As an example, Fife mentioned a request her office received in November 2023 for communications about a resolution the council approved that called for a ceasefire in Gaza. Fife said her office received “thousands” of emails, each of which her staff would have to go through to redact personally identifying information, such as email addresses or phone numbers.

Councilmember Carroll Fife posted a video in September describing the California Public Records Act and her office’s engagement with it. Credit: Instagram (screenshot)

Councilmember Carroll Fife posted a video in September describing the California Public Records Act and her office’s engagement with it. Credit: Instagram (screenshot)

“We have 10 days to respond to the public by law, to get that information to the individual or the public that asked,” Fife said. Later in the video, Fife added that “we have to do it within 10 days or face some sort of challenge there.”

This is not quite right. The law requires government agencies to make a determination within 10 days. A determination is simply a requirement to tell the requester whether or not there are any records responsive to their request. But there’s no deadline for when officials need to turn over records, other than an obligation to make them “promptly available.”

The Oaklandside, which filed two requests with Fife’s office for communications about the Gaza resolution, never received a notice from Fife’s office about whether or not she had any responsive records. We still haven’t received that notice or any records for those requests, which were filed 686 and 694 days ago, respectively.

Overall, Fife has completed five of the 15 requests we’ve sent her between 2023 and 2025.

Some of the others that we’re still waiting on:

We have filed 14 public records requests with Councilmember Janani Ramachandran, who has fully or partially completed 10.

Ramachandran has not responded to or completed four requests we sent her in June and July. including:

Ramachandran did not respond to interview requests.

In 2024, Ramachandran received an award from the Society of Professional Journalists for using Oakland public records herself, to “hold city leaders accountable” for failing to process police dispatcher applications.

We filed six requests with Councilmember Rowena Brown, who took office in January. She has responded to three of those requests and turned over records. Shortly after we contacted Brown for an interview, her office completed another request, releasing copies of her calendar for the first half of 2025. It took Brown 79 days to complete this request. There is one remaining uncompleted request from July for communications with her about a resolution to support a state energy bill. Brown’s office also released records related to communications with PG&E lobbyists. However, we believe there are more her office has, based on materials we got from a different councilmember.

The Oaklandside will publish a follow-up story exploring the problems underlying Oakland’s public records system and why it takes officials so long to comply with the law.

“*” indicates required fields