San Francisco General Hospital’s Ward 86 derived its name by being sited on the sixth floor of Building 80, an aging red brick tower on the north end of the sprawling hospital campus. It was the first HIV/AIDS outpatient clinic in the nation, opening its doors on Jan. 1, 1983.

Until its abrupt closure after last week’s stabbing of social worker Alberto Rangel, allegedly by one of the clinic’s patients, it hosted a drop-in clinic five days a week.

It was never built to accommodate such a use. Building 80, notes Dr. Paul Volberding, one of the clinic’s founding doctors, was erected a century ago and originally designed to house pediatric patients. It does not resemble any modern clinic most people have ever visited; there is no reception area separating the elevator and the middle of a working clinic.

“Anyone with any kind of weapon,” Volberding says, “there’s just no barrier.”

Volberding was a doctor at Ward 86 from Day One in 1983 until 2001. He describes security in his era as “minimal,” but adds that “we did not feel the urgency the clinic feels today.” This is, in large part, because Ward 86 now serves an entirely different demographic of HIV/AIDS patients.

In the earlier days of Ward 86’s history, its patients often had middle-class lives and college degrees and jobs. But HIV/AIDS patients with squared-away lives are now more often privately insured and treated in private practice.

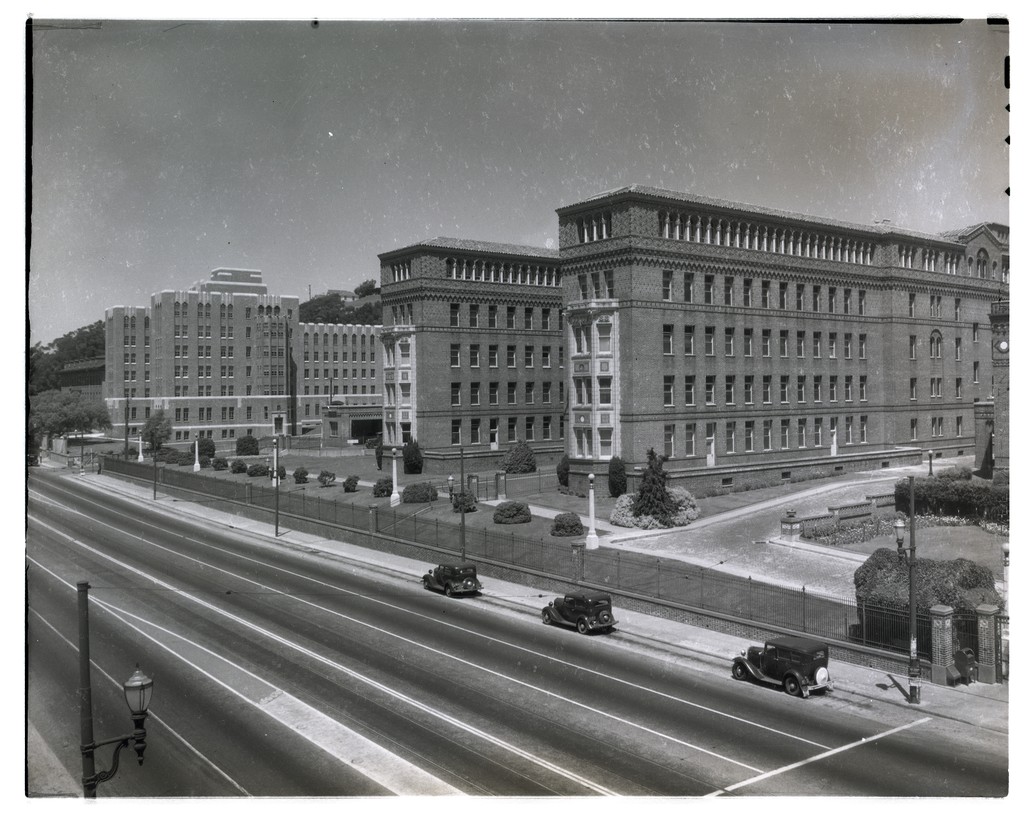

San Francisco General Hospital Buildings 80 and 90 circa 1937. Photo courtesy UCSF, San Francisco General Hospital archives.

San Francisco General Hospital Buildings 80 and 90 circa 1937. Photo courtesy UCSF, San Francisco General Hospital archives.

Starting in the 1990s as treatment became more widely available, the outpatient demographic at Ward 86 began to dramatically shift to patients who are harder to reach. The HIV/AIDS patients at the clinic nowadays are more likely to be poor, homeless and suffering from mental illness and substance use.

Medical workers say threats of violence have become increasingly commonplace at Ward 86. Rangel’s alleged killer, Wilfredo Tortolero-Arriechi, was a regular patient here. He was known, feared and reported.

“This could have been avoided on so many fucking levels,” a colleague of Rangel’s who witnessed the attack told Mission Local. “We knew three weeks ago about this patient.”

Rangel’s colleagues say that he, too, reported Tortolero-Arriechi’s behavior weeks ago. Hospital workers say that, on the day of the attack, the 34-year-old patient made threats against a Ward 86 doctor, which spurred the deployment of a sheriff’s deputy to the clinic to protect that doctor.

Staffers at Ward 86, however, have expressed frustration that the deputy was not keeping an eye out, specifically, for Tortolero-Arriechi. At the time of the stabbing, an eyewitness told Mission Local that the deputy was not within eyeshot of the attacker. It’s unclear why a sole deputy was dispatched to the clinic.

Mourners gather at a statue in front of San Francisco General Hospital for a vigil in memory of Alfredo Rangel. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

Mourners gather at a statue in front of San Francisco General Hospital for a vigil in memory of Alfredo Rangel. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

The deputy “should have been watching the entrance doors to the building, making sure that every individual was safe from this person, not just a doctor,” said Jessica Hoopengardner, a Ward 86 nurse. That deputy “should have stayed at the front entrance, never allowing this man to walk into the building.”

The sheriff’s department unconditionally defended its deputy.

“Our deputy followed all required procedures,” reads a statement from the department. “He was onsite to ensure the doctor’s safety, remained on the Ward after an initial search for the subject, and when he heard a commotion in the hallway, immediately responded. Upon witnessing the assault in progress, he intervened without hesitation, detained the subject, and secured the scene. His quick actions allowed medical staff to begin life-saving measures for the victim without delay.”

San Francisco General Hospital’s Ward 86 today. Photo courtesy UCSF.

San Francisco General Hospital’s Ward 86 today. Photo courtesy UCSF.

In the wake of Rangel’s killing, Department of Public Health director Daniel Tsai pledged to hire an independent firm to review the hospital’s security procedures. Sheriff Paul Miyamoto last year consented to allow private security at the hospital alongside his deputies due to “a shortage of Sheriff’s Office personnel,” according to an October 2024 letter. Still, security could be scant.

Hoopengardner said the sight of a deputy at Ward 86 was unusual. Mission Local is told that Ward 86 has no regular assigned security details.

But a lack of security is not necessarily unusual at San Francisco General Hospital. Even in a ward where deputies are regularly assigned, like psychiatric emergency services, they often don’t fill their security shifts, according to Department of Public Health data obtained by Mission Local.

At that psychiatric center, there were no sheriff’s deputies present for security shifts 90 percent of the time in November (645 hours out of 720).

Deputies were present at the psychiatric center far more often in July: 68 percent of the time. But then their recorded presence began to drop precipitously. In August it was just 51 percent. In September it dropped again, to 24 percent, then to 18 percent in October and 10 percent in November.

For 17 days in November there was no recorded deputy presence whatsoever.

The sheriff’s department could not confirm or deny the health department data. But it countered that if a deputy was pulled away from the psychiatric emergency services even briefly, the health department would count this as “no presence.”

“In most cases,” the department said in a statement, “a deputy is assigned to that post and is on campus responding to calls, completing reports or assisting elsewhere.”

Nurses in the past have called for the removal of sheriff’s deputies from the hospital. At an internal Department of Public Health briefing on Monday, hospital CEO Susan Ehrlich said keeping Ward 86 both accessible and secure was a “delicate balance.”

When security began scanning the clinic’s patients with wands after Rangel’s killing, “we realized that some of the patients would feel that a barrier existed,” Ehrlich said. A former employee of Ward 86 remembered asking four years ago that metal detectors be installed to avoid the need for armed security.

Troubles at Ward 86

Back in Ward 86, workers had expressed concerns over threats of violence at the clinic long before Rangel’s stabbing. Alejandro, a fellow social worker there, said a doctor had been choked by a patient in recent years, and he remembered multiple instances of people being bitten by dogs at POP-UP, the ward’s low-barrier clinic for homeless people living with HIV.

“As a social work team, we have advocated for more protocols to be in place,” Alejandro said. “That has not happened.”

“I’ve always worried about my safety,” added another healthcare worker. She and other colleagues described a dysfunctional help alert button by the front desk. Once, she said, it took 40 minutes for security to respond.

When psychiatric concerns arise, other clinics are often understaffed or full, leaving hospital workers with limited options of where to send troubled patients before issues escalate. Just days before the stabbing, Alejandro referred a patient who was threatening violence to Dore Urgent Care Clinic, a facility for people in psychiatric crisis. The clinic declined to take the patient.

A bronze statue of a mother and her children stands in front of the hospital. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

A bronze statue of a mother and her children stands in front of the hospital. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

“Blame our society,” said Volberding, the Ward 86 founding doctor. “We have not dealt with the fact that people don’t have places to live and have substance-use issues and don’t have access to any kind of effective treatment. This certainly has been a problem in HIV-affected populations in the past 20 years.”

“What we’re seeing with HIV is reflected in a lot of what is happening in public health,” he continued. “We are dealing with an impoverished group of people with a lot of other societal challenges. … There is a certain lack of control and the potential for violence is there.”

Volberding was shocked by what happened at Ward 86 last week. But not surprised. If the space was inadequate from its inaugural day, Volberding says it’s now unworkable in the wake of Rangel’s violent death.

“I would think that what is going to have to happen is a new physical space will have to be designed and built,” he said. “The security at outpatient clinics will have to be comparable to what you’ll find at the trauma center at the General. That is what is going to have to happen.”

Additional reporting by Mariana Garcia, Eleni Balakrishnan and Abigail Vân Neely