Hal is having trouble adjusting to first grade. At night, he tells his sister, Harper, who’s in the third grade. Harper, who often has to mother her baby brother, offers Hal some words of comfort … while sullenly smoking a cigarette.

Wait, what?

Well, here’s the thing about the siblings in Cooper Raiff’s new eight-episode series debuting Sunday on the streaming service Mubi, “Hal & Harper”: Their mother died suddenly when the kids were 2 and 4, respectively, forcing both to grow up too fast while also getting emotionally stuck.

So, while we see glimpses of actual kids playing Hal and Harper before their family is decimated by death and depression, Raiff plays Hal both as a 22-year-old in the present and as a 7-year-old while Lili Reinhart plays Harper at 24 and 9. Those childhood versions contain glimmers of their adult selves (Harper also reads “One Hundred Years of Solitude” during recess) while the adult versions contain the children they still are.

The family portrait gains heart-rending nuance when Raiff shows Hal and Harper’s dad (Mark Ruffalo), who plunged into a deep depression 20 years ago, which accelerated the trauma caused by their mother’s sudden absence. In the present, Dad and his girlfriend Kate (Betty Gilpin) are selling the family home and about to have a baby, stirring up anew the cauldron of emotions for Dad and the kids.

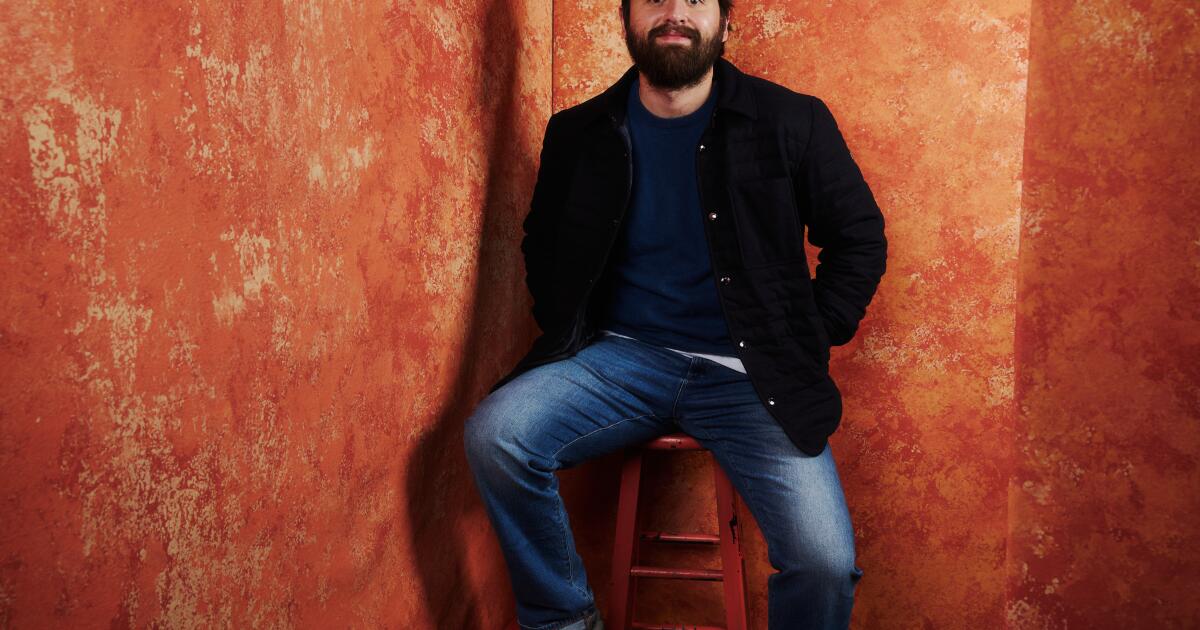

“Hal and Harper are just flailing,” says Raiff, who initially insisted to friends the show was not autobiographical, saying, “This is not my life.”

Cooper Raiff and Lili Reinhart in “Hal & Harper.” The pair of actors play the titular characters both as adults and children.

(Mubi)

Raiff says his girlfriend, Addison Timlin (who has a recurring role in the show), succinctly punctured the notion that he conjured these characters “out of thin air,” by telling him the show is “about the pain that we forget we remember.”

When Raiff was 4, he experienced a major event in his family — he hasn’t spoken about it publicly in detail — that shaped his perspective on his life and work. In his feature film, “Cha Cha Real Smooth,” Raiff played Andrew, whose mother was bipolar; like Hal, Andrew grew up quickly but stunted, has issues of codependency and hates being alone. (Harper, meanwhile, “carries all the pain of the family,” Raiff notes.)

Raiff, whose storytelling is concise and economical, underscores those emotions with handheld camerawork as director of the series: “Usually you’d ask, ‘What’s motivating a handheld shot,’ but here everyone feels shaky, so we’d ask, ‘What’s motivating a stable shot?’ The shots I like best in the show are where we’re up in their eyes and it feels so immediate.”

As for the show’s cast, the unadorned psychological truths in the story is what drew them in. “Cooper sent me a 300-page PDF of the whole thing and it was the best script I’d ever read,” says Reinhart. “I felt really sad when I finished reading it because I didn’t want it to end.”

Reinhart related to Harper because as a kid, she was an “old soul” who had “a melancholy air” and found it difficult to fit socially. To better understand Harper, she read Hope Edelman’s “Motherless Daughters” and now sees her character as being “in a constant state of dissociation, having lost her mom and immediately assuming the role of caretaker in the family. She covers up with armor and if joy creeps through, she smacks it away.”

Gilpin was impressed by Raiff’s attention to detail. “You could just tell from Page 1, how much care and thought he had about the backstory of every single character and what every moment should look like,” she says. “The show feels very anti-algorithm; it’s not treating the audience like they’re stupid. There’s so much intangible inexplicable behavior between people that feels exactly like what a family is.”

Betty Gilpin plays Kate in “Hal & Harper,” who is having a baby with Dad (Mark Ruffalo). “You could just tell from Page 1, how much care and thought he had about the backstory of every single character and what every moment should look like,” she says.

(Mubi)

Raiff created his first version of “Hal & Harper” as a web series when he was in college. He created a web series set in a bedroom where the younger versions talked every night about what their dad had said that day. Eventually he expanded his palette, adding the 20-something Hal and Harper, plus Dad and Kate, whose characters come to the fore in the third episode, which darkens the series’ tone.

“I’ve had so many people talk about how painful it was to watch that relationship and how it took them a little bit to get past the third episode,” Raiff says. He credits Gilpin, who was pregnant with her second child during filming, with providing insights that deepened her character. “She had so many amazing ideas and she clarified how important it was that Dad is missing out on the pregnancy journey.”

Raiff had initially placed the series at FX, but he says executives at the network were unsettled by Dad and Kate’s story. “Every note was about making it a college show and one exec said, ‘You should go home and watch “Greek,” the ABC Family show,’” Raiff recalls. “I knew I was in trouble then.”

The network wanted Dad and Kate gone, but Raiff held tight to his vision. “The third episode is my favorite episode,” he says. “I know shows have to be funny and entertaining and the show is called ‘Hal & Harper,’ but the heart of the show is Dad realizing he wasn’t a dad and telling himself the only way to give the universe and my kids some sort of justice is just to lay on this floor [in their old house] and just stay here.”

As a result, Raiff got his show back and set out to make it independently; Reinhart signed on as executive producer to lend clout and Raiff budgeted the entire season for what he says was half the cost of the pilot at FX.

They received funding from Lionsgate, but after shooting, found fresh resistance. Raiff says executives wouldn’t watch the whole series, so he showed an hour-long sizzle reel at a screening. “Execs walked out sobbing, saying, ‘I can’t go back to work. I have to call my therapist and my parents,’” he recalls. “We were high-fiving each other. But there was not a single offer. Later I learned they thought, ‘What do we do with this? It’s so emotional.’”

Cooper Raiff on the set of “Hal & Harper,” which he also directed. He chose to make the show independently after encountering some resistance to the story. (Mubi)

Reinhart was despairing. “It was so heartbreaking when we thought the show may never be seen because it doesn’t fit a bingeable content square box,” she says, adding that she thought, “I will never do independent television again.”

Then Raiff took “Hal & Harper” to the Sundance Film Festival in January, which led to Mubi buying it. In an email, Mubi’s chief content officer Jason Ropell said seeing a finished product made committing much easier. “It removes any uncertainty around execution,” adding that while there are risks, he can “see an appetite in the market for this model.”

Indeed, “Hal & Harper” is part of a small but growing trend of indie TV that hopes to reimagine the industry the way indie film did. Actor and creator Kit Williamson (“Unconventional”) notes that there had been an initial burst in the last decade where web series were made on the cheap and successful ones were bought by major players, citing Issa Rae’s “Awkward Black Girl,” which led to “Insecure” on HBO — a network that also bought “High Maintenance” — while Netflix snatched Williamson’s “Eastsiders.”

But the new path involves fully financing an entire ready-for-TV season to sell. Williamson chose this route for “Unconventional” because he wanted to make an unabashedly queer relationship show “written without respectability politics in mind, so I’d need to find a different pathway.” (He sold it to the queer-oriented streamer Revry and it can be seen on platforms like Philo and Pluto.)

Gilpin notes that the industry is playing it safer and safer, with networks even running “second watch screenings” — to make sure a person scrolling on their phone can still follow the plot of the show on their TV. “We have to keep pushing each other to make things that don’t pass that test,” she says.

Michael Polish, an indie filmmaker who has ventured into indie TV with “Bring on the Dancing Horses,” says just as filmmakers once went outside the studio system to make more challenging fare, so will showrunners.

“There’s a general frustration with the development process bottleneck and the hesitancy to take risks,” Williamson says, “though whether or not it’s a gold rush is yet to be seen.”

Lili Reinhart, who co-stars in “Hal & Harper,” also signed on as an executive producer. “It was so heartbreaking when we thought the show may never be seen because it doesn’t fit a bingeable content square box,” she says.

(Mubi)

The biggest success story has been the Duplass brothers, who sold “Penelope” to Netflix, and “The Creep Tapes” to Shudder. Additionally, comedian Shane Gillis had a Netflix hit with “Tires” and Michele Palermo, a playwright and TV writer, landed “Middlehood” on Prime Video.

The trend is even taking root in animation (which costs more to produce), says Orion Tate, founder and chief creative officer at Buck, which has several shows in development he hopes to make independently. “We want to build these shows from the ground up and then get a deal,” he says.

Claire Taylor, chief programming officer at SeriesFest, which showcases episodic TV, says more studio executives and production companies are coming to SeriesFest to shop.

“Filmmakers like Mark Duplass and Cooper Raiff are showing you can tell the story you want to tell,” she says before cautioning, “it will take more of these success stories for filmmakers who don’t have that cachet.”

Indeed, Polish’s series can be seen in Europe and on Paramount+ in Canada, but not yet in America. Polish says the indie film world has more distributors and festivals. “A lot of different avenues have been set up over the years,” he says, adding that Sundance adding a section for TV pilots was a big step for this field. Raiff adds that independent TV will gain a legitimate foothold, but only when a streamer sets up its own department for buying independent shows.

And Reinhart has come around on the idea, saying, “independent TV is challenging to say the least, but I was so lucky to have this experience.”

“We may not be seen by the largest group of people ever, but it’s a show that sticks with you,” she says. “I would rather have made a show that really impacts the people who see it than a bigger one that just sits on a streamer forever and no one cares.”