Participant characteristics

The analytic sample comprises 116 participants, after excluding four individuals who were determined to be ineligible based on a review of demographic data. Fifteen participants completed the survey more than once, resulting in 89 unique individuals represented in the study. Participants’ sociodemographic and reproductive health characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fifty-three percent of participants were currently or recently pregnant (within the past year). About half of the participants were between 25–34 (32%) or 35–44 years of age (20%). Thirty-six percent of participants identified as Black or African American, and 38% identified as Latine. Forty-six percent had an educational level beyond high school, and 19% had not completed high school. About two-thirds (63%) of participants were unemployed, and nearly half (49%) were on income assistance. Two-thirds (65%) of participants had public insurance (e.g., Medi-Cal, Medicaid, etc.). Thirty-seven percent of participants were single, and 35% lived with a romantic partner. Twenty-four percent of participants had at least one preterm birth, and 29% had a prior pregnancy loss.

Table 1 Univariate distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, obstetric history, and care discrimination experiences among pregnant, postpartum, and family participants in the San Francisco Family & Pregnancy Pop-Up Village, San Francisco, CA, N = 89Accessibility of PV

The mean accessibility score was 76.0 (SD = 21.0) overall, 73.7 (SD = 24.4) for the pregnant and postpartum participants, and 78.5 (SD = 18.6) for family members (Table 2). The mean accessibility score for Black participants was 78.0 (SD = 20.9) compared to 74.6 (SD = 22.5) for participants from other racial and ethnic groups.

Table 2 Distribution of standardized Accessibility and Acceptability scale scores among pregnant, postpartum, and family participants in the San Francisco Family & Pregnancy Pop-Up Village, San Francisco, CA, N = 116Factors associated with accessibility

In bivariate analyses, several factors were associated with perceived accessibility of PV. Participants aged 25–34 years, those who did not disclose their English proficiency, and those working full-time scored on average 6.5, 17.2, and 16.1 points lower, respectively, than participants aged 15–24 years, proficient in English, and unemployed. Also, those who lived in other areas of San Francisco, reported only “somewhat” having social support, or had private or employer-sponsored insurance, scored on average 15.9, 10.7, and 12.9 points lower, respectively, than participants living in the Bayview, reporting strong social support (“Yes, definitely”), and having public insurance. Participants who did not disclose their food insecurity status and experienced discrimination during their usual prenatal care encounters on some occasions scored on average 16.2 and 15.8 points lower, respectively, than those who often experienced food insecurity and had no experiences of discrimination during prenatal care encounters. Participants with some level of college education, who owned a home or apartment, or were single, scored on average 11.9, 6.3, and 13.2 points higher, respectively, than participants who did not earn a high school diploma, lived in a homeless shelter, or were married or partnered and living together (see Supplementary Table 1 for full sample analyses and Supplementary Table 2 for subgroup analyses).

In the final multivariate model (Table 3), accessibility was significantly associated with English proficiency level, residence, medical insurance status, and experiences of discrimination during prenatal care encounters. Participants who preferred not to disclose their English proficiency level scored, on average, 23.8 points lower than participants who reported being proficient in English (95% CI −40.4, −7.2). Participants who lived in other areas of San Francisco, on average, scored 16.6 points lower than participants who lived in the Bayview (95% CI −24.7, −8.6). Participants who did not have any medical insurance scored, on average, 31.5 points lower than those who had public insurance (95% CI −52.0, −11.0). Participants who experienced discrimination during their usual prenatal care encounters on some occasions scored, on average, 11.0 points lower than those who did not experience discrimination (95% CI −20.8, −1.2).

Table 3 Multivariate mixed-effects linear regression model of select predictors on the Accessibility score, N = 116

Participants’ responses from the in-depth interviews supported the quantitative data on accessibility. While most reported minimal burden of accessing PV services, some reported barriers, including lack of language-concordant navigation services for Spanish-speaking participants and provider follow-up.

Facilitators of accessibility

Participants cited several factors that made accessing services easier, including provider responsiveness, short wait times, the physical infrastructure of PV events, and PV’s central location and proximity to their residence. They also highlighted the importance of providers who met them where they were and made a genuine effort to understand and address their needs. As one Multiracial pregnant participant explained:

“Because you can go up to them, but 9 times out of 10, they are going to come up to you and ask you, ‘Do you need some of these services?’ or ‘Try this service out. ‘Because I never got any acupuncture before and that was a new experience for me. But she reached out to me. I didn’t – it wasn’t like I was going over there, so yes.” —Multiracial pregnant participant less than 30 years old

Other participants noted that services at PV were more accessible, citing notably shorter wait times; some reported waiting only a few minutes before being seen by a provider:

“And it wasn’t like a long line. It was just like if I walked to the table, I would be like the first person or the third. But it wasn’t like a long wait. So, it was like I got to visit the majority of all the programs.” —Multiracial pregnant participant, between 30 and 44 years old

Participants noted that PV’s central location and proximity to their residence made it convenient for them to walk or take public transportation to reach PV:

“You’re [Pregnancy Village] just right off 3rd and McKinnon. That’s just half a block I have to go. Usually, them blocks are long. So, 104 and up there – they [are] long. But it was just a little hop, skip, and a jump, and I was right there. It’s easier – you didn’t have to walk to catch the bus, or the T-train, the 24, the 54. All of it is right there. Even the 15 comes down that way. So, it’s very easy to get there.” —Black family member, 45 years old or above

Barriers to accessibility

While participants generally reported a low burden in accessing and receiving services at PV events, some identified challenges related to the physical layout, inadequate service navigation support, information overload, and lack of provider follow-up. Additionally, difficulties in learning about available services were attributed to the lack of designated navigators to guide them through the services:

“I thought it was going to be like a meeting with […] somebody who could give you details [like a prenatal group], and then I didn’t see anybody, so I was confused. And nobody explained it to us until someone told me, ‘You can go there and get some information.’” —Latine pregnant participant, between 30 and 44 years old

A few participants noted that lack of provider follow-up after the event made it difficult to access the services they needed, as this Multiracial pregnant participant recounted their experience:

“Well, with X organization, my experience was good up until they didn’t call me back. They didn’t follow up. So, they were not accountable for their word. So, I felt like [having connected with them] was pointless because getting that interaction with them and setting that all up with a doula was like the main focus of why I wanted to go. And that’s why my doctor encouraged me to go.” —Multiracial pregnant participant, less than 30 years old

Acceptability of the PV

The mean acceptability score was 91.9 (SD = 14.4) overall, 90.5 (SD = 15.7) for pregnant and postpartum participants, and 93.4 (SD = 12.9) for family member participants (Table 2). The mean acceptability score for Black participants was 94.2 (SD = 12.8) compared to 90.3 (SD = 15.3) for participants from other racial and ethnic groups.

Factors associated with acceptability

In bivariate analyses, several factors were associated with perceived acceptability of PV. Participants who spoke Spanish, had limited English proficiency, and had at least one preterm birth scored on average 8.1, 4.9, and 8.0 points lower, respectively, than participants who spoke English, were proficient in English, and did not report a history of preterm birth. Those who had no medical insurance, did not disclose their food insecurity status, and experienced discrimination during their usual prenatal care encounters on some occasions scored on average 18.0, 11.5, and 11.4 points lower, respectively, than participants who had public insurance, had no food insecurity, and had never been discriminated against during prenatal care encounters. Participants who worked part-time, owned a home or apartment, and did not experience food insecurity scored on average 7.3, 6.5, and 5.3 points higher, respectively, than those who were unemployed, lived in a homeless shelter, and often experienced food insecurity (see Supplementary Table 3 for full sample analyses and Supplementary Table 4 for subgroup analyses).

In the final multivariate model, acceptability was significantly associated with language, medical insurance, and experience of discrimination during prenatal care encounters (Table 4). Participants who spoke Spanish found PV less acceptable than those who spoke English, scoring, on average, 7.9 points lower (95% CI −15.6, −0.2). On average, participants without medical insurance scored, on average, 16.3 points (95% CI −28.0, −4.7) lower than those who had public insurance. Participants who experienced discrimination during their usual prenatal care encounters found PV less acceptable than those who did not experience any discrimination during care encounters, scoring on average 10.3 points lower (95% CI −15.5, −5.0).

Table 4 Multivariate mixed-effects linear regression model of select predictors on the Acceptability score, N = 116

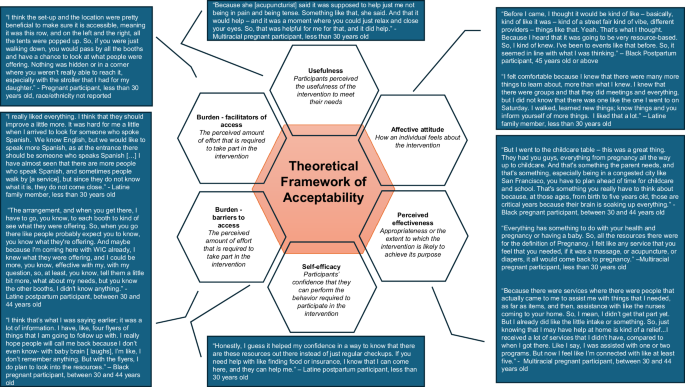

Participants’ responses from the in-depth interviews supported the quantitative data on acceptability. We summarized the data on the acceptability of PV using six deductive domains based on the TFA20. The definitions of the TFA domains and additional excerpts of the outlined domains are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) domains and corresponding quotes.

This figure displays the domains of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability, paired with illustrative quotes that capture participants’ perspectives on each domain. Designed by Jorrín Abellán, I.M. Hopscotch Building: A Model for the Generation of Qualitative Research Designs (2016)52.

Anticipated affective attitude

When asked about their expectations of PV prior to attending, some participants anticipated a health fair-type setting focused on pregnancy-related resources and information. Upon reflection, many reported that these expectations were met, highlighting the inviting and uplifting atmosphere, as well as the abundance of resources, including mental health and wellness services such as massages and acupuncture, and prenatal offerings such as diapers, wipes, and clothing. Participants also noted gaining valuable awareness and knowledge of services designed to improve their pregnancy experience:

“[I expected PV to be] kind of similar to what it is. So, definitely, organizations and businesses that have resources for pregnant people. I didn’t expect there to be that many giveaways for pregnant people or services in terms of massages. So, more just like resources, knowing like, ‘Hey, this is where you can get XYZ. This is available to you here in San Francisco.’ And the education part, I kind of did expect, like the breastfeeding education.” —Pregnant participant, less than 30 years old, race/ethnicity not reported

A few participants, however, reported having no expectations prior to the event, as they were unfamiliar with community-centered events that offered both information and tangible resources. For example, one family member noted:

“Well, you know, I didn’t have any expectations. I never heard of anything like that, never been to a community gathering of that sort. So, I didn’t have a whole lot of expectations. But, as I read the flyer and read the different organizations that were going to be there, I kind of felt good about attending and felt like it was worthwhile.” —Black family member, 45 years old or above

Experienced affective attitude

Participants generally characterized the PV atmosphere as positive, vibrant, community-centered, down-to-earth, and healing. When asked how they felt upon arrival, many expressed feeling welcomed, excited, and filled with anticipation. For instance, one Black postpartum participant had this to say:

“I was happy. I was like, ‘Wow. Look at all of this.’[…] because I had my son there – he’s seven-and-a-half months. And I was like, “Look!” He really loved the color of the tents and the way the tents were kind of blowing in the wind. He loved the live music. It was just like, “Wow. Okay. Yes!” And it was like it was our first time being out in community ever. And so, I was pleased that it was such a warm, welcoming, fun environment for us to walk into. You know? You walk in and you see like the bags of groceries that, you know, were being handed out and things like that.” —Black postpartum participant, 45 years old or above

Participants also expressed their appreciation and surprise at the introduction of new services and resources at each event, noting these additions as an unexpected but welcome enhancement:

“I was excited to see what was new, because you guys don’t always have the same things; sometimes what you all give away and what you all do for us is unexpected, especially for the resources. I didn’t think the CalWORKS individuals were going to be there for the moms that don’t have any type of income.” —Multiracial pregnant participant, age not reported

Some participants described their initial impressions of PV as a community-centered, curated space where Black individuals could gather, connect, and access pregnancy-related services and resources. They shared that being surrounded by other Black individuals or expectant mothers made them feel at home—free to express themselves and engage in activities without fear of judgment:

“I felt kind of like at home, because I wasn’t the only one pregnant, or there were mothers who were there that were very comfortable breastfeeding and stuff. So, seeing that was like, oh, ‘this is a place for us to just be open and free without no judgment.’” —Multiracial Pregnant participant, 30–44 years old

“It was about seeing Black individuals coming together without fussing or arguing. We were there. We enjoyed each other. We laughed. That makes you feel good when Black individuals come together and everybody enjoys themselves […] I looked around. I’m like, ‘Wow, this is neat! This could help a lot of young girls.’ You know, teach them. That’s what we need to do is teach them the right way.” —Black family member participant, 45 years old or above

The community-centeredness of PV was especially salient in the context of the social isolation experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, as illustrated by the account of this Black postpartum participant:

“I was pregnant from 2020 all the way through 2021. That was like the height of when everything was like shut down and isolated. We were having fires. I couldn’t go outside to walk even, hardly. It was extremely isolating. And so, one of the benefits that I don’t think that you all are necessarily picking up on is that, for individuals who have been isolated because you’re trying to follow COVID protocols and all of that, it was healing to just be out in the fresh air, in the sunshine, with other mothers. Like that, in and of itself, was the healing thing for me.” —Black postpartum participant, 45 years old or above

Participants reflected that attending PV had made them more aware of shared interests with others in their community, which, for some, had given rise to a desire to become more actively involved in their community:

“Going to the Pop-Up just opened my eyes to there’s so many individuals out there that I have common ground with. And we can all work on ourselves together. We could help each other. Some individuals don’t know where to start. So, that’s where I’m at. It kind of inspired me to definitely see what I could do for my community. But first, yeah, I felt very good.” —Latine postpartum participant, between 30 and 44 years old

Most participants said their expectations were met, with several noting that they were exceeded. This was largely attributed to the plethora of resources and services available, which addressed physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being:

“[My expectations] were met. I received a lot of information from different groups on childcare, doula services, even when the baby starts growing her first teeth, even a dentist that’s nearby my house. And chiropractic services for pregnant women – I didn’t even know you can get realigned as a pregnant woman.” —Black pregnant participant between 30 and 44 years old

Others noted that their expectations were met because they felt acknowledged and valued at PV, as one pregnant participant shared: “I really felt acknowledged and seen, and individuals were really trying to take care of me because they saw that I was pregnant.” —Pregnant participant, less than 30 years old, race/ethnicity not reported

However, a few participants reported that their expectations were unmet, citing insufficient guidance on the availability and use of relevant resources:

“Yeah, so once again I have, you know, totally different expectations. So when I went there, and I see just a bulletin and nobody, nobody is, like, welcoming you, you know. But, if someone doesn’t know anything, like where do you go? I just had to ask around, and they told me, like, ‘Okay, you can get some information here in that first booth.’ But I didn’t really get that information well.” —Latine postpartum participant, between 30 and 44 years old

Self-efficacy

Overall, participants expressed increased confidence in accessing services both within and beyond PV following their attendance. This enhanced confidence was attributed to PV’s strong referral system, exposure to new services, and the provision of clear and comprehensive information by service providers:

“I feel like it was a linkage sort of situation. So that if I needed something more extensive, then I would have the information to know like where to go, who to talk to – all of that – maybe even set up an appointment. So, when I did need to go and access that deeper level of services, I could go out into the community, and then do that.” —Black postpartum participant, 45 years or above

However, a few participants reported that participation in PV did not increase their confidence in accessing new services, primarily due to limited awareness of the full range of available services. In these cases, information was typically provided only by organizations with which they were already enrolled, thereby restricting exposure to new services:

“I don’t think so, I mean, the only, the only things that I saw that was convenient for me was the programs that I already know. But anything else that I don’t know, I don’t know. The Homeless Prenatal, like I’ve been a customer before. And then for, for WIC, you know, I’m a client already. So, anything else, I have no idea.” —Latine pregnant person between 30 and 44 years old

Appropriateness

Participants generally perceived the services as appropriate and aligned with their expectations. Several noted that the services effectively addressed the needs of pregnant individuals and their families, reinforcing their relevance and value:

“I feel like they’re appropriate because the need is so great right now. A lot of individuals are on hard times. A lot of individuals are struggling. And, with these organizations being implemented the way they have to help families, it just kind of lightens the load. It gives me just that great feeling of knowing – even though I’m on hard times right now – that I don’t have to worry because I can get the help that I need until I’m in a better place and can do better for myself. So, I feel like it’s totally appropriate.” —Black family member, 45 years old or above

Participants viewed the services as appropriate, particularly because they provided pregnancy-related education and addressed gaps in breastfeeding education:

“Even though I had already been through breastfeeding when I first started with my first child, I realized it is really something that women need support on. Even though it is natural, it doesn’t come naturally to a lot of people. And just knowing that there was this booth that really educated individuals on the latch, and how breast milk is established, and that it might take a while.” —Pregnant participant, less than 30 years old, race/ethnicity not reported

A few participants, however, perceived certain services as inappropriate, citing a lack of focus on pregnancy-specific support. As one Latine pregnant participant explained:

“I went for information for pregnancy, and when I went there, I didn’t find anything kind of related, at least, you know, with my eye at the beginning. And then I guess it was a couple of books for that, but I didn’t see anybody or was expecting to see more people, you know, kind of with a similar concern that I have, and I see nobody.” —Latine pregnant participant between 30 and 44 years old

Perceived effectiveness

Participants generally perceived PV to be effective, noting its uplifting environment and focus on centering Black women:

“I think they did a good job of providing that really positive atmosphere. Especially I feel like it was centering around women of color and Black women, and sometimes we will often feel like society looks down, like ‘oh you are pregnant.’ I think they did a good job of making it feel like a positive thing you’re pregnant.” —Black pregnant participant, between 30 and 44 years old

Other participants attributed PV’s effectiveness to its responsiveness to community needs, including proactive outreach and the delivery of resources in an accessible way:

“I like that you guys like to be part of the community, and you like to see what is going on in the community. It is really hard right now, especially to be homeless, and not have a lot of resources – that’s one thing I like – for you guys to go and give back to the community and say ‘Hey, we have resources. We want you guys to come out and have a good time as well.’ And on top of that, it also helps with depression.” —Multiracial pregnant participant, age not reported

Usefulness

Participants generally regarded the services and resources provided at PV as useful. Some participants cited pregnancy and postpartum-related education, such as newborn hygiene and nutrition, as well as mental health support, as key reasons for its perceived usefulness:

“Well, at the one table that was in the middle, I overheard them talking about how to give your baby a bath, how to do this with your baby, do that with your baby. That was so cool, because I saw individuals with babies and stuff. I was kind of listening a little bit. They were sitting there talking about their kids, what their kids do, what their kids eat, what they didn’t eat, what’s good for them, and what’s not good for them. And that’s what they need. They need to know more about baby nutrition.” —Black family member, 45 years old or above

Several participants found PV useful because it offered educational resources for children and child-related activities at events:

“I saw how they were with the kids. The little kids were up there drawing, doing all this stuff. You know, they were really, I think they were really supportive, helping all the little kids up there doing the thing.” —Black family member, 45 years old or above

Service recommendations

In the in-depth interviews, participants shared several recommendations to improve the PV model. These included adding or improving specific services, such as provider follow-up with interested individuals; provision of more food, particularly for pregnant individuals; expanded pregnancy education sessions; more support and education around mental health, including postpartum depression and managing the stress of newborn care; and additional child-focused activities and resources, particularly those that promote parent-child engagement:

“I think they did have a booth for, like, mental health support. But definitely more education around health and depression, and the fourth trimester, and postpartum essentials that are really helpful for a mother for recovery, and then also for a baby. Just that it’s not just about the pregnancy or when you give birth, but then the first few weeks or the month after that might be really intense on women.” —Black pregnant participant, less than 30 years old

“If you guys have like some sort of guided mommy and me activity like with music and stuff like that, where you could just kind of come over with your baby and be led in some like movement activities and stuff. That would be fun.” —Black postpartum participant, 45 years old and above

Others shared infrastructural recommendations, including the provision of more comfortable seating, the engagement of navigators to guide visitors and share information—particularly in their preferred language—and enhanced outreach to ensure broader community awareness of available services.

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses in which missing and duplicate responses were excluded, we identified no differences in standardized acceptability or accessibility scores (see Supplementary Table 5). The acceptability score was 90.8 (SD = 15.2) overall (N = 85), 90.5 (SD = 15.9) for pregnant and postpartum participants (n = 45), and 91.2 (SD = 14.5) for family members (n = 40). The accessibility score was 74.5 (SD = 22.6) for the main sample (N = 87), 71.0 (SD = 24.2) for pregnant and postpartum participants (n = 46), and 78.5 (SD = 20.2) for family members (n = 41).