The East Bay bluegrass scene has many “parents,” but it’s likely undisputed that no single figure contributed more across a range of endeavors than Mayne Smith.

A skilled steel guitarist, vocalist and songwriter who grew up in Berkeley, he was also a pioneering scholar and steady hand who played a key role in transforming Freight & Salvage in Berkeley from a shaky storefront venture into a nonprofit roots-music powerhouse. Active almost until the end of his life, he died at home in the Richmond hills on Nov. 12 at the age of 86, following complications from a fall.

“Mayne was a very honest, straightforward guy, sometimes to a fault,” said his longtime music partner, guitarist Mitch Greenhill. “He was very loyal and devoted to traditional music but ready to take it to new places.”

In some circles Smith was best known as a songwriter whose pieces were recorded by peers such as Rosalie Sorrels, Laurie Lewis, and Linda Ronstadt (in her early days with the Stone Poneys). Among musicologists he was recognized for writing the first scholarly treatise on bluegrass, “Bluegrass Music and Musicians: An Introductory Study of a Musical Style in Its Cultural Context,” a 1964 book that expanded on his Indiana University master’s thesis.

While he had demanding non-musical jobs over the years Smith was a dedicated working musician passionate about collaborating with other artists. He caught the bug in his early teens in Berkeley, where his father, Henry Nash Smith, was a UC Berkeley professor who played an essential role in the creation of American studies.

“Mayne was a very honest, straightforward guy … He was very loyal and devoted to traditional music but ready to take it to new places.”

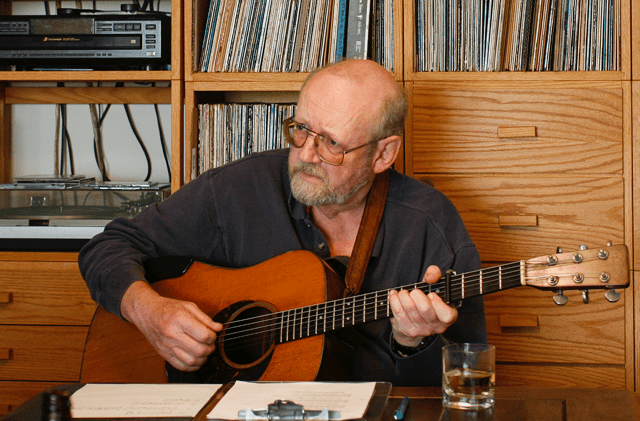

— Mitch Greenhill, longtime music partner of Mayne Smith (Photo courtesy of Smith family)

Musician was part of foursome that founded Bay Area’s first bluegrass band

The local folk music scene was already rolling in the mid-1950s when Mayne and a circle of friends started taking guitar and voice lessons from Laurie Campbell, a local folksinger they discovered via KPFA. A few years later, Smith was at the center of a cadre of Berkeley High folkies who were enamored with flatpicking blues, old time songs and bluegrass.

Smith’s circle included Scott Hambly, Neil Rosenberg and Pete Berg, and in 1959 the foursome founded the Bay Area’s first bluegrass band, the Redwood Canyon Ramblers (named after a cabin in Redwood Canyon where they would gather to jam). Performing mostly at Berkeley schools, the group paved the way for a bevy of colorfully named combos, including the Hart Valley Drifters, which included future Grateful Dead collaborators Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter, and the Black Mountain Boys with Garcia, David Nelson and Eric Thompson.

Rather than following his father into academia after his seminal bluegrass study for Indiana University’s Folklore Institute, Smith lit out for Los Angeles, plunging into the vibrant mid-1960s folk scene that centered on westside venues such as the Ash Grove and McCabe’s Guitar Shop. Playing with emerging stars like Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal, John Fahey, David Lindley, and Richard Greene, he gradually began to focus on songwriting, while his instrumental arsenal expanded to include Dobro and pedal steel guitar.

By the time he returned to the East Bay in 1969 Smith was no longer a bluegrass purist. He was also exploring overlapping permutations of folk rock, country, and country rock, which all came into play in the Frontier Constabulary, a popular band with Mark Spoelstra and Mitch Greenhill. After years as a solo guitarist, he’d found his most satisfying musical identity working with partners.

“He did not like to play alone,” his wife Gail Wilson-Smith said. “He wanted to play with other people. In the first years of our marriage we had people over frequently to play music and hang out.”

When Spoelstra departed in 1970 to resume his solo career, Smith and Greenhill continued to perform widely around the region as The Frontier through 1974. The group was included in a memorable Folkways anthology, “Berkeley Farms: Oldtime and Country Style Music of Berkeley,” produced by Mike Seeger.

Smith and Greenhill, who is also a noted producer, reconnected several years later and started touring and recording as a duo, a connection that continued throughout their lives.

“We spent a lot of time on the road, and Mayne was a damn good traveling companion,” Greenhill said. “Every now and then we’d run into some of his old bluegrass buddies and I think he felt ambivalent about having half abandoned bluegrass.”

From Frontier Constabulary to the rise of Freight & Salvage

Mayne Smith (right) spearheaded the transition of Freight & Salvage in Berkeley into a nonprofit with the Berkeley Society for the Preservation of Traditional Music. Courtesy of Mayne Smith family

Mayne Smith (right) spearheaded the transition of Freight & Salvage in Berkeley into a nonprofit with the Berkeley Society for the Preservation of Traditional Music. Courtesy of Mayne Smith family

The Frontier Constabulary was the group that first brought Smith into a little Berkeley coffeehouse on San Pablo Avenue called Freight & Salvage. When the Freight’s founder Nancy Owens decided to move on, Smith spearheaded the venue’s transition into a nonprofit organization in 1983 with the Berkeley Society for the Preservation of Traditional Music.

“At that time, the Freight was the place for bluegrass,” said Suzy Thompson, the prolific Berkeley roots musician who served on the Freight’s board for years.

“Having Mayne take the helm at that point was a huge help in raising the money to take over the business. He had a really deep and longstanding reputation in the bluegrass world as a scholar and player, a lot of gravitas and respect. I don’t know if the Freight would have been able to continue without him stepping in.”

When gigs thinned out in the mid-1970s Smith started working at luthier Hideo Kamimoto’s guitar and violin shop in Oakland, a job he held from 1977 to 1983. It wasn’t long after he left Kamimoto that Smith and Gail bought a house in Richmond.

The location kept him close to the acoustic music scene in Berkeley and gave his wife an easy commute to her work as an educator at various East Bay schools, including a stint as a project assistant at Richmond High School and principal of Riverside Elementary School in San Pablo. He didn’t have many opportunities to perform in Richmond, though there were occasional gigs at Hotel Mac in Point Richmond.

Smith wasn’t a prolific recording artist, but he left a significant discography, including collaborations with Greenhill such as 1979’s “Storm Coming,” 1986’s “Back Where We’ve Never Been,” 2014’s “The Lost Frontier” and “Live 1976” (which was released in 2016). On the 1971 album “Travelin’ Lady,” the Frontier accompanied Rosalie Sorrels, and in 2008 Smith released “Places I’ve Been: a Songmaker’s Retrospective.”

Smith is survived by Wilson-Smith, his son Noah Smith, his granddaughter Nahla Smith, his sisters Harriet and Janet Smith (a noted folk musician herself), and an expansive community of musicians with whom he played and shared songs over the years. The Freight will host a celebration of Smith’s life and music on March 10.

We’ve opened our comment section for this story. Share your memories of Smith.

“*” indicates required fields