After paying all her bills, Araceli Salinas said she didn’t have enough money left to take her family out for a pizza. The high cost of living at her home in Madera, California, was worse in the summer months. For years, her monthly electric utility bills routinely hit the $300 range.

“With PG&E that high, sometimes you have to buy just the basics for you and your kids,” said Salinas, in an interview with Straight Arrow News.

Download the SAN app today to stay up-to-date with Unbiased. Straight Facts™.

Point phone camera here

For Salinas, the basics meant rice, beans, tortillas, bread and milk. She works providing in-home care to seniors — a job that provides flexibility for her to spend time with her four kids. Even while keeping the air conditioning set to a warm 78 degrees, summertime electric bills have long been a burden for Salinas.

“I was barely saving a little money to buy groceries because I had to pay my electricity,” Salinas said. “I believe it’s a big percentage in California who lives in the same situation.”

She is right.

California’s electricity prices have skyrocketed, particularly for the three major investor-owned utilities in the state: Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas and Electric.

California has the second-highest electricity prices in the United States, behind Hawaii. And in recent years, the gap between California and the national average has widened. On Thursday, the California Public Utilities Commission will vote on the three companies’ return on equity for 2026. The commission is expected to decrease the utilities’ profit margin by .35%, which could keep the rate stable, for now. But the amount of money the companies spend on generating electricity and running the grid — not their return on equity — is the main driver of rate increases. The state has several programs aimed at blunting the burden of high costs. Still, families like Salinas’ in the heat-prone Central Valley pay some of the nation’s highest monthly bills.

How expensive is electricity in California?

California’s electricity rates have been higher than average for decades. In 2001, 1.5 million households faced blackouts and PG&E was forced into bankruptcy when market manipulation led to sky-high prices to generate electricity. The energy crisis left a lasting impact on electric rates, as ratepayers absorbed some of the losses. The state was also an early adopter of renewable energy, which locked utilities into long-term contracts before the cost of wind and solar plummeted.

For the first decade of the 21st century, a typical California resident paid around 4 to 6 cents more per kilowatt hour of electricity than the national average. The difference began ticking up in the mid-2010s, and as of September, California residents pay an average of 32 cents per kilowatt hour compared to the national average of 14 cents, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

How that rate translates to monthly bills depends on consumption habits. The latest national data shows Californians consume much less electricity per household at 540 kilowatt hours a month versus a national average of 880. However, a report from the California Public Utilities Commission notes that customers in hotter parts of the state can use 790 kilowatt hours.

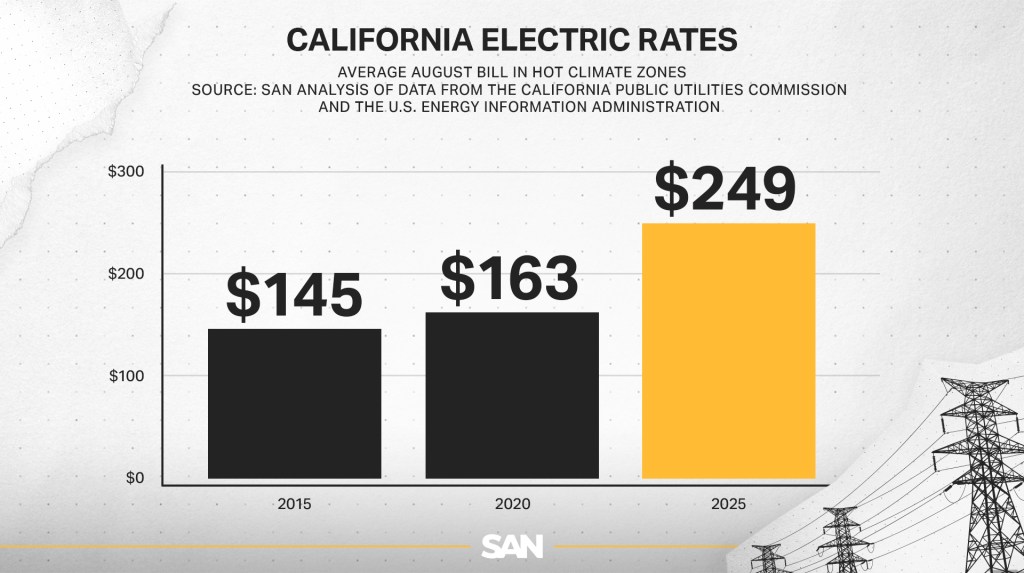

In 2015, the monthly August bill for a typical customer in a hot climate zone like the Central Valley would have been about $145. In August of 2020, that same amount of electricity would cost $163. By August 2025, it cost $249.

What role do wildfires play in electricity costs?

But the consequences of the energy crises and renewable energy build-out merely set the stage for the larger driver of California’s cost increases: spending on the power distribution system. Much of that is linked to wildfires, but industry watchdogs say more oversight of utilities is needed.

“Wildfire-related costs are one of the clearest differentiators between California and the rest of the country,” said Maria Castillo, a senior associate at the national nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute.

Between 2019 and 2024, the three largest investor-owned utilities in California increased their average rates by 16.2 to 17.9 cents per kilowatt hour — the sharpest increases in the U.S. by far. Only five other investor-owned utilities across the country increased rates by more than 10 cents over the same period.

Fourteen of the 20 most destructive wildfires in California history have occurred in the past decade. At least four were officially caused by powerlines, with the cause of several more undetermined or under investigation, according to CalFire.

If a utility company is legally found negligent, investors are obligated to pay costs, including settlements with owners of destroyed property. However, ratepayers — including commercial businesses and residents like Salinas — can still wind up saddled with costs from wildfire damage.

Severin Borenstein, a professor and expert on energy economics at the University of California Berkeley, explained how even if a utility company is not found negligent for sparking a wildfire, “if the utility equipment is involved, they are held responsible. This is under what’s called inverse condemnation.”

Claims under California’s inverse condemnation law can add up to billions of dollars. And large fires can burn hundreds of thousands of acres, adding costs to replace powerlines. But wildfire-related costs extend even beyond damages.

The cost of future fires

“At the same time, we’ve been dealing with future wildfires,” Borenstein told SAN. That involves trimming vegetation, installing upgraded conductors and in some cases relocating powerlines underground, which is “tremendously expensive,” Borenstein said.

The end result is soaring costs on the power distribution system. While acknowledging that wildfires are an important factor, some policy analysts believe utility companies need to find ways to cut costs.

“Year in and year out, [utility companies] go to the Public Utilities Commission, and they propose increased spending,” said Bernadette Del Chiaro, senior vice president at the nonprofit Environmental Working Group in Sacramento. Del Chiaro, who has spent 30 years working on energy and environmental policy, told SAN the commission “basically rubber stamp these spending increases, and they don’t really scrutinize it.”

An analysis from economist and consultant Richard McCann found that since 2020, the direct wildfire costs only account for around 10% of utility revenue increases. He argued most of the money spent on distribution is not going toward fixed costs and called on the PUC to perform an audit.

“It’s not clear what they’re spending on in order to get such big increases. It’s a black box,” McCann said.

Expressing doubt in McCann’s 10% figure, Borenstein said it’s difficult to parse how much of the investor-owned utilities’ spending increases are tied to wildfires. In an email to SAN, he cited a post by fellow Berkeley academic Meredith Fowlie, which stated, “the CPUC is hindered by limited access to utility cost data, inconsistent cost categories across proceedings, and a limited ability to reconcile actual expenses with prior authorizations.”

A 2025 report from the Rocky Mountain Institute found PG&E spent 24% of its revenue on wildfire-related costs in 2024, while the other two large investor-owned utilities spent 11% and 12%.

How are communities burdened?

Unbiased. Straight Facts.TM

Residential electricity rates in California are twice as expensive as the national average

With rapidly increasing electric bills, consumers’ risk of falling behind increases. Castillo analyzed data from the PUC on customers who are in debt to the utility companies.

“Utility disconnections are concentrated in areas within the Central Valley and Bay area,” Castillo told SAN, in an email.

Some of the Central Valley’s largest cities, Fresno, Bakersfield and Stockton, had the highest average number of customers disconnected each month.

Karina Gonzalez, a Fresno resident and co-executive director of the nonprofit GRID Alternatives, told SAN, “these communities have been often forgotten and are left behind.”

Gonzalez described how people in her community cope with high bills. In the summer and winter, she said people who cannot afford to heat and cool their homes temporarily relocate to warming and cooling centers run by the local government. Others use open flames to stay warm, but that can be deadly.

“We have high rates of low-income and impoverished individuals that are striving just to get by,” Gonzalez said. “When they open their electric bill, their cries can be heard.”

What is the state doing to help?

GRID Alternatives performs no-cost rooftop solar installations for qualifying low-income households. The nonprofit receives grant funding from the state through DAC-SASH, a fund to provide free solar installations for disadvantaged communities.

For customers below certain income thresholds or receiving assistance like SNAP, the state also provides rate discount programs such as California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE), offering a 30-35% bill reduction, and Family Electric Rate Assistance (FERA), providing an 18% discount.

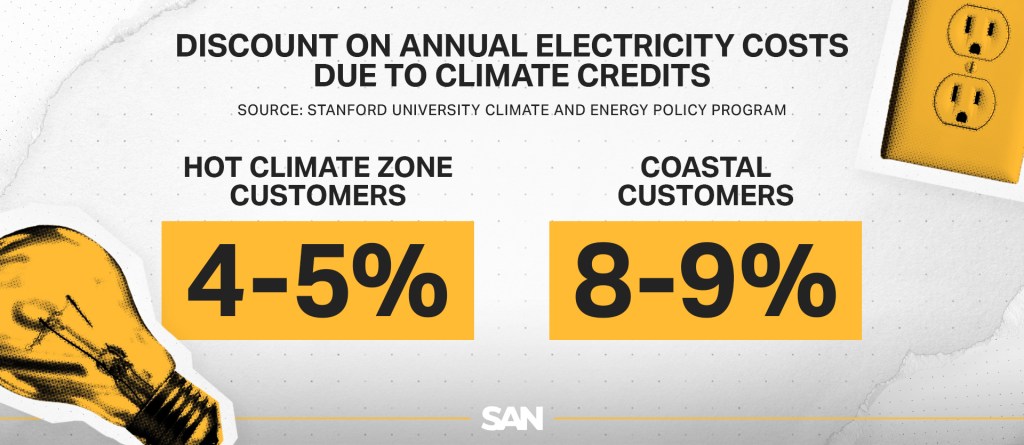

And there’s California climate credits, a twice-annual discount provided to all California utility customers every April and October. As it exists now, each utility company provides a flat discount to all of their customers. In 2025, PG&E customers received $116.46 in total.

Lane Smith, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University, is the lead author of a white paper detailing how climate credits could better target the communities most burdened by high electric bills.

“The program is currently not fair,” Smith said. Since each customer receives an equal credit, Smith said that discount goes further in temperate climates, but in hotter areas — many of which have a higher share of low-income households — the same discount makes less of an impact on their bills.

According to his research, utility customers in hot climate zones such as the Central Valley see a 4-5% discount on their annual electricity costs thanks to the climate credits. Residents along the coast, however, receive a 8-9% reduction.

“You can’t fault people for living in a more temperate area where they’re not exposed to extreme temperatures, but some people need more help with their electricity bills,” Smith told SAN.

Even with the CARE discount, Salinas said her monthly electric bills could reach $300 in the summer, and the twice-annual climate credits — an average of less than $10 a month — “really don’t make a big difference,” she said.

Smith’s white paper models three ways to redistribute climate credit funding — something he hopes the state legislature will take up.

“If you’re just trying to use the same pot of money on the same group of customers, you’re going to not see big affordability impacts,” Smith said. “You could actually take this pot of money and use it to impact a subset of customers who are really hurting.”

Why is there so much controversy around rooftop solar?

There’s one more factor behind California’s electricity costs, though its role is hotly debated: rooftop solar.

As rooftop solar installations increased, demand for power from the grid remained relatively flat. Residents who install solar panels do not need to buy as much electricity, yet they still rely on distribution systems operated by utility companies when the sun isn’t shining.

“Distribution systems are almost all fixed costs,” Borenstein said. And while those costs rise, utility companies collect less revenue from the subset of customers equipped with rooftop solar.

“As more and more people have put in rooftop solar, generally wealthier than average, we’ve seen more of a cost shift,” Borenstein said, as the utility companies raise rates to make up for the lost revenue. And the burden falls on people who do not have rooftop solar.

Borenstein was appointed to the board of governors of the state’s electric grid operator CAISO by Gov. Gavin Newsom and then elected to serve as its board chair. In his view, the rooftop solar cost shift is a “huge chunk of the increase that we’ve seen over the last decade.”

But advocates for more distributed energy resources like rooftop solar believe the technology has generated cost savings for all consumers: “Solar capacity deferred a bunch of investment in generation and in transmission,” McCann said.

Del Chiaro said the cost shift is a “myth” and called rooftop solar the “unsung hero” of meeting growing electricity demand. As people used more power from their roofs, demand for power from the grid leveled out. “Fixed costs do not increase,” she added, arguing that utility spending is out of control and that the opposition to rooftop solar aligns with the interests of utility companies.

“The utilities hate anything that looks and talks like rooftop solar for that very reason that it cuts against their profits,” Del Chiaro said. “They don’t want a smaller grid. They want a bigger grid.”

Start your day with fact-based news.

For residents facing sky-high summer bills, rooftop solar is perhaps the most effective solution.

Salinas applied for rooftop solar through GRID Alternatives. She met the income requirements and was approved for a no-cost installation. In May 2024, her home in Madera was fitted with rooftop solar. The difference in her bills was stark.

“That helps a lot,” Salinas said. In 2023 without panels, Salinas said her bills during the summer months were $200-300. In 2025, with rooftop solar, her highest bill over the summer months was $83.

“Now that I have the panels, I can have a little extra money so I can go, like, at least once a month and go eat with my kids, or get a pizza, things like that,” Salinas said. “Before, I wasn’t able to do that.”