Saday Osorio Cordoba’s job as the sole social worker at the Colombian consulate in San Francisco has never been what you’d call easy. Her client base spans not just California but Alaska, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. According to the latest census, 36,000 Colombian nationals live in these states, but Osorio Cordoba guesses it’s closer to 250,000. If something goes wrong for them, it often lands on her plate.

She helps find Colombians who are missing or trafficked, detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, separated from their families, or are critically ill and desperate to leave the U.S. and return home.

President Donald Trump’s reelection has made consulate work more difficult than ever, especially for those representing countries with large contingents of immigrants in the U.S. Now the workers in these agencies are not only handling passport and visa paperwork but are acting as first responders at the front lines of emergency services amid the immigration crisis.

This new workload for officials of foreign governments is another example of the toll of the anti-immigration agenda on people living and working in the U.S. Several Latin American consulates report being inundated with difficult, high-stakes cases. Some are so busy that they said they wouldn’t be available to speak to the press until January.

“It’s always been challenging, but now it’s insane,” Osorio Cordoba said. The consulate reports that the number of emails and phone calls it has received from people in desperate need of help has quadrupled from last year. “We are working more than ever. We knew it was going to be a big challenge, but we never expected this amount,” she said. “I have to move rapidisimo.”

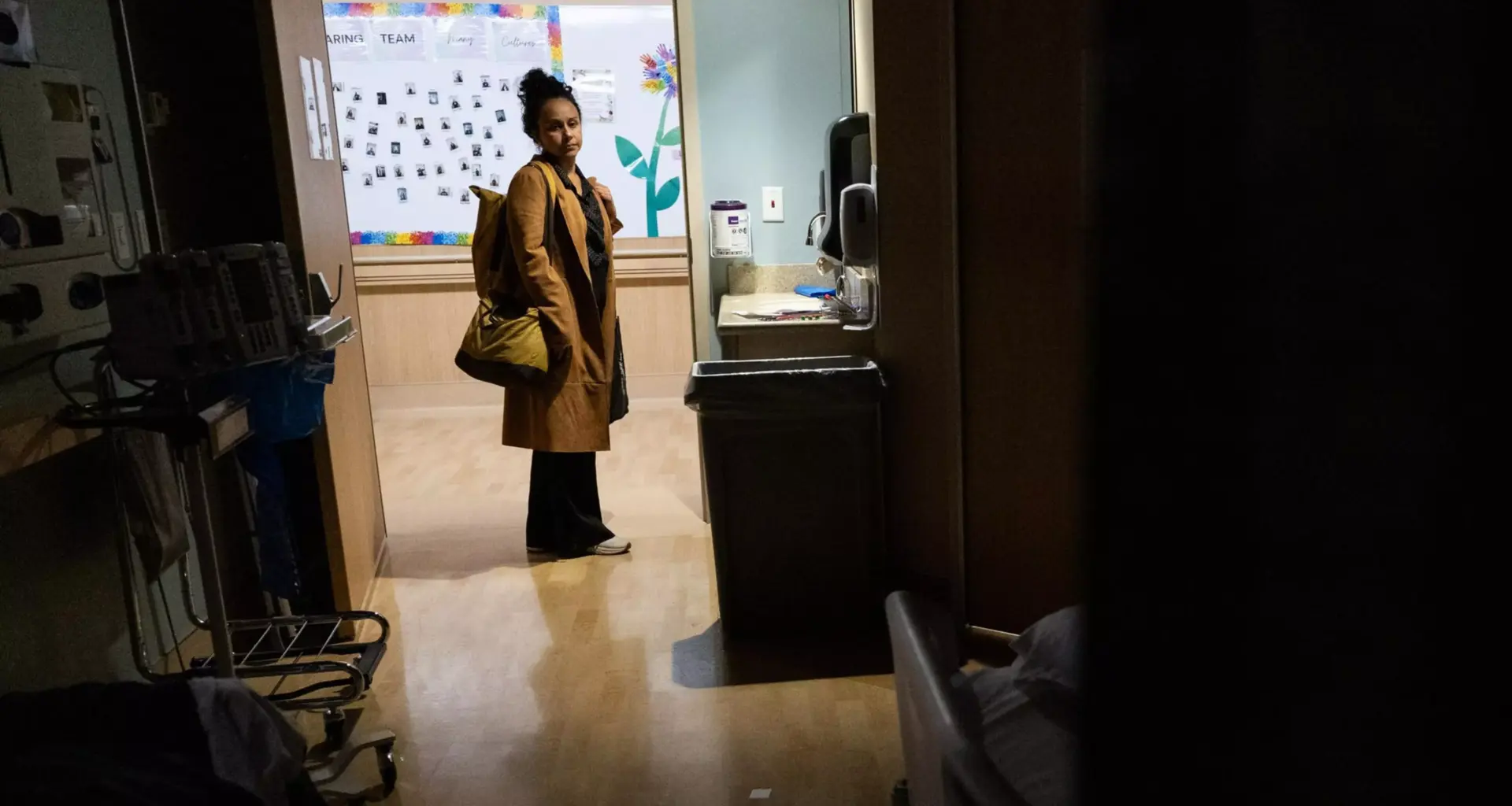

Saday Osorio. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Saday Osorio. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Her professional life resembles that of a firefighter, moving from one dire emergency to the next. Last week, she helped a young man dying of cancer return home to see his mother one last time. On Tuesday, she met with a young woman whom she’s been trying to help escape drug addiction and sex trafficking. There are two families whose children disappeared into the foster care system after the parents were detained by ICE.

And then there’s the case that’s been dogging her for weeks: an undocumented man who contracted an infection while in police detention in Alaska, which resulted in him losing three limbs. In order to help him, she has had to move faster than ever, and possibly move him across state lines, putting herself at such legal risk that even the consulate wouldn’t be able to protect her.

Osorio Cordoba came to San Francisco in 2009 at age 31 to be with her mother, who lived here. But a month later, her mom died of a stroke. Shortly afterward, Osorio Cordoba found herself without a place to live. “I went to a shelter,” she said. “I was homeless for a day.”

Like many new arrivals to the U.S., Osorio Cordoba was helped by a more established countrywoman, a stranger who gave her a free place to stay until she could get a job and rent an apartment.

She paid that forward, organizing events at the Colombian consulate, then volunteering there for a year. In 2021, the consulate hired her as a cultural attaché. But she found that as much as she loved promoting her country’s arts in the U.S., she spent more time helping Colombians with emergencies. Soon, she became the consulate’s full-time social worker.

Much of what a consulate does is straightforward paperwork. Colombia’s consulate in the Financial District has four functionaries, two advisors, two interns, and many volunteers, but most deal with basic consular activities, such as issuing passports and promoting Colombian businesses.

That leaves Osorio Cordoba and a small team of volunteers with more serious cases than they can possibly manage. The top-ranking diplomat at the consulate, the consul general, can sometimes make a phone call to a sympathetic local or federal official to resolve issues. But many cases require someone like Osorio Cordoba who can drop everything to jump on a plane, find disinterested decision makers, and doggedly appeal to their sense of humanity to avert a crisis.

“She is on the front lines,” said Sonia Marina Pereira Portilla, the Colombian consul general of San Francisco. “She is a formidable woman.”

Not every foreign national needs a consulate to help them. A lawyer in the U.S. can help with many of the immigration and criminal matters that occupy Osorio Cordoba. Nonprofits can help, too, especially in places like San Francisco, where pro bono legal providers are prevalent. But for poor immigrants living in rural areas or in places actively hostile to them, the consulate serves as a beacon.

When Osorio Cordoba heard about Alex Valencia Bonilla, thousands of miles from San Francisco and with no other hope, she knew immediately he’d become her top priority.

The undocumented 23-year-old was arrested in February in Alaska following a dispute with his roommates. He was incarcerated at the Fairbanks Correctional Center in conditions he said were unsanitary. “The place was filthy,” Valencia Bonilla said in Spanish. “The bed and bedsheets were covered in this nasty liquid. And the toilet and sink didn’t have running water.”

Alex Valencia came to the United States by boat, fleeing violence in Colombia. He contracted a deadly bacteria while detained in Alaska and woke up from a coma with three limbs amputated. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Alex Valencia came to the United States by boat, fleeing violence in Colombia. He contracted a deadly bacteria while detained in Alaska and woke up from a coma with three limbs amputated. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

A representative of Alaska’s Department of Corrections described allegations that Valencia Bonilla’s cell was unsanitary as “categorically false.”

After 11 days in jail, Valencia Bonilla suffered cardiopulmonary arrest, the result of a bacterial infection acquired at FCC, according to doctors who attended to him afterward.

Valencia Bonilla arrived at Alaska Regional Hospital in Anchorage on March 11 in a coma. Over the following week and a half, as he battled spreading necrosis, doctors amputated three of his limbs and the two smallest fingers on his remaining right hand. “When I woke up from my coma, I was how you see me now,” Valencia Bonilla said, gesturing toward his body.

A charity paid for Valencia Bonilla’s operations and three months of recovery at Alaska Regional.

When he came out of the coma, he had a tube in his throat, preventing him from speaking. A nurse at the hospital emailed Osorio Cordoba about the case early in Valencia Bonilla’s treatment. Osorio Cordoba coordinated with his family while he was unable to communicate. “I was actually the last person in my family to talk to her,” Valencia Bonilla said.

She became his sole advocate. As the last day of his hospital stay approached, she negotiated with the facility, trying to buy him more time. He had open wounds, could barely operate his manual wheelchair, and had nowhere to go. But on the day before he was supposed to be discharged, he was put into a taxi headed for a homeless shelter where staff wouldn’t be able to care for him. The shelter sent him right back to the hospital. When he arrived, hospital staff threatened to call the police if he didn’t leave.

Alaska Regional Hospital declined to respond to specific allegations about Valencia Bonilla’s case, citing HIPAA privacy laws. “Transfers to post-acute care facilities or shelters with medical respite options are made with prior arrangements and an understanding of the patient’s medical conditions and needs,” the facility said in a statement. “Alaska Regional Hospital is committed to providing quality care for our patients.”

Saday Osorio and Alex Valencia spend time together before having a traditional Colombian dinner at a Sequoia Hospital waiting room. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Saday Osorio and Alex Valencia spend time together before having a traditional Colombian dinner at a Sequoia Hospital waiting room. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Osorio Cordoba spent several hours texting Valencia Bonilla’s friends in Alaska, looking for a place for him to crash. But he couldn’t land just anywhere. He needed intense medical attention. “I called everybody he knew in Alaska,” Osorio Cordoba said. “No one could take care of him.” The whole time, she kept Valencia Bonilla on the phone while he sat in his wheelchair on a street corner in Anchorage.

Osorio Cordoba finally secured him a shelter bed and then, a few days later, a place at a private physical rehabilitation facility in Alaska. “I told them that I had money to pay them,” she said. “That was a lie.”

Eventually she found enough money to pay for a couple of months at the rehab facility, but it was a short-term fix. So she concocted a plan: Get him to California, where she hoped the state’s generous public healthcare could cover his recovery.

Valencia Bonilla was in no condition to travel by himself. So Osorio Cordoba would have to fly to Alaska and accompany him back to the Bay Area, all while avoiding ICE detention. But this was illegal: Knowingly transporting undocumented people is a federal felony.

The consulate couldn’t sign off on Osorio Cordoba going as an employee. But on Oct. 13 she went to Anchorage, picked up Valencia Bonilla from his rehab facility, and brought him to the airport. “I was so afraid,” Osorio Cordoba said. “I knew I could be arrested.”

Their worst nightmares came true. After the pair had checked in for the flight, ICE officers patrolling the airport approached and separated them. They told Osorio Cordoba that they planned to detain Valencia Bonilla. She watched the officers who were interrogating him.

“They shook him and threatened him with deportation,” Osorio Cordoba said. “I said to myself, ‘Dios mio, don’t grab him like that, look at the condition he’s in.’”

Fearing what would happen to him in ICE detention, she pleaded with the officers to let Valencia Bonilla self-deport to Colombia that day, saying she’d pay for the ticket. The officers refused.

So she took a different tack. She’d printed a thick stack of dozens of pages detailing Valencia Bonilla’s care protocols — everything from wound care to prescription drug schedule to his complex medical history. When she handed it to the officers, asking if they were prepared to offer this level of care, they called over their supervisor, who inspected Valencia Bonilla. “She was horrified by his condition,” Osorio Cordoba said. The ICE supervisor let the pair board the plane to SFO.

“It was a miracle,” Valencia Bonilla said.

Once they arrived in California, Osorio Cordoba found Valencia Bonilla temporary care at a hospital in Redwood City, then longer-term care in Los Altos, and arranged for full Medi-Cal coverage for his treatment and prostheses. When she visits, she brings KFC. His hospital room is packed with clothing and food donated by a network of Colombians who live nearby, organized by Osorio Cordoba.

She said Valencia Bonilla has started to feel like family, which is why his case has affected her so deeply. “I’m in therapy because of Alex,” she said.

Saday Osorio rests on Alex Valencia’s bed at Sequoia Hospital. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

Saday Osorio rests on Alex Valencia’s bed at Sequoia Hospital. | Source: Manuel Orbegozo for The Standard

The job can be overwhelming. Several times a year, she has to inform a worried mother that her child has died in the U.S. Three times last year, she had to tell a family that their relative had committed suicide in the U.S. “It’s a horrible part of my job,” she said, “a job no one wants to do.”

Sometimes — often — not even her. She has submitted her resignation three times so far, but she always ends up rescinding it.

“This job is like a toxic relationship,” Osorio Cordoba said. “I can’t continue. I try to get out of it. But it won’t let me.”

She sees no end in sight to the deluge of cases coming across her desk since Trump reassumed the presidency. “We are in a total crisis right now,” Osorio Cordoba said. “If my people aren’t doing good, then I’m not doing good.”

But for as much as it wears her down, her family and coworkers say Osorio Cordoba was built for this kind of impossible, risky work.

“It doesn’t surprise me that she landed there,” her daughter Valeria Rueda Osorio said.

Rueda Osorio remembers being a second grader in Cali, Colombia, during a heavy rainstorm that flooded the city. At the end of the school day, a wide stream of water separated her and her classmates from the area where their parents waited for them. “I was scared,” said Rueda Osorio. “No one knew what to do.”

She said her mother waded into the water, which swirled up to her thighs, and crossed the stream. “She picked me up and she gave me a piggyback ride back to the dry place,” said Rueda Osorio. “And then she did that with the other kids too.”