California is expected to begin reissuing approximately 17,000 non-domiciled commercial driver’s licenses that the state had planned to revoke following federal enforcement pressure. The decision comes despite ongoing corrective action requirements from FMCSA and raises fundamental questions about federal enforcement authority when a state openly defies compliance directives.

State transportation officials confirmed to sources that the Department of Motor Vehicles will begin restoring the contested licenses to immigrant drivers who received 60-day cancellation notices on November 6. The state has not clarified the specific process but points to the D.C. Circuit Court’s November 13 emergency stay of FMCSA’s interim final rule restricting non-domiciled CDL eligibility.

What California apparently misunderstands, or is choosing to ignore, is that the court stay addressed only the September 29 interim final rule. It did not address the separate compliance failures FMCSA documented during its 2025 Annual Program Review, which found that approximately 25% of California’s non-domiciled CDLs were improperly issued under regulations that existed before the emergency rule was ever published.

The federal government threatened to withhold more than $150 million in highway funding from California over these pre-existing violations. Those threats remain fully in effect regardless of the court’s stay of the new rule.

Understanding California’s legal exposure requires separating two distinct issues that the state appears to be deliberately merging.

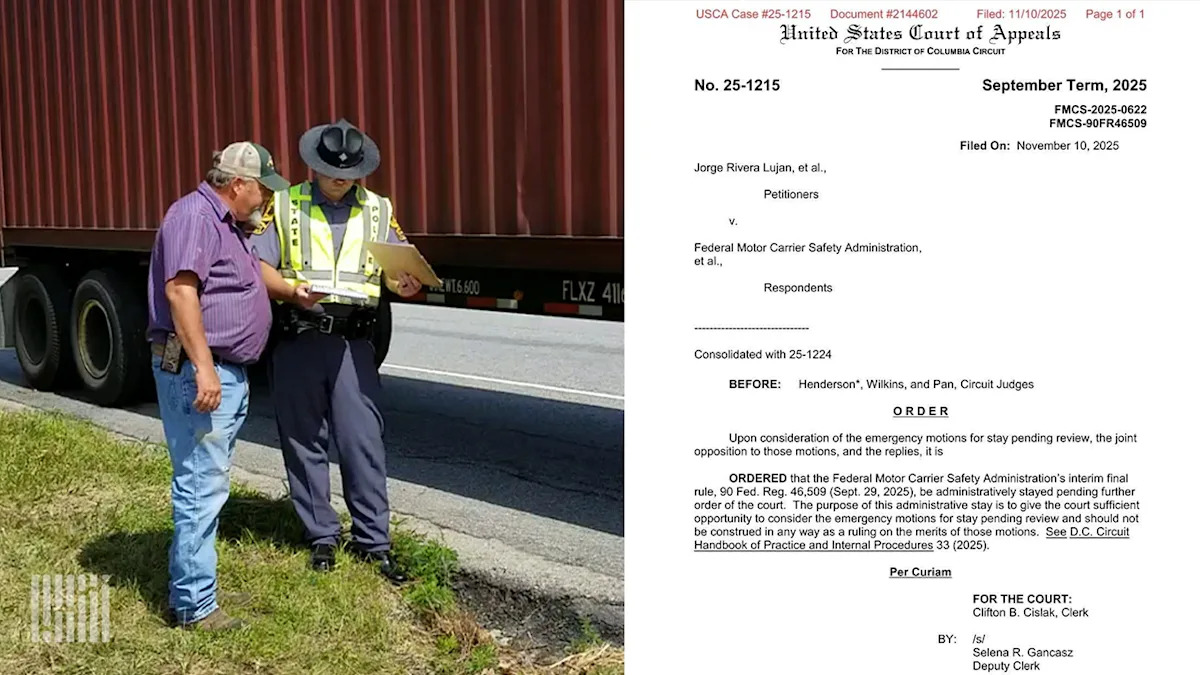

Problem One: The Interim Final Rule. On September 29, 2025, FMCSA issued an emergency interim final rule titled “Restoring Integrity to the Issuance of Non-Domiciled Commercial Drivers’ Licenses.” This rule dramatically restricted the eligibility of non-domiciled CDL holders to H-2A, H-2B, and E-2 visas, excluding asylum seekers, refugees, and DACA recipients. The D.C. Circuit Court stayed this rule on November 13, finding petitioners were “likely to succeed” on claims that FMCSA violated federal law, acted arbitrarily, and failed to justify bypassing standard rulemaking procedures. With this rule stayed, states can theoretically continue issuing non-domiciled CDLs under pre-September 29 regulations, except for states under corrective action plans.

Problem Two: Pre-Existing Compliance Failures. FMCSA’s 2025 Annual Program Review found California had been violating federal regulations that existed long before the interim final rule. The agency documented systemic failures: CDLs issued with expiration dates extending years beyond drivers’ lawful presence authorization, licenses issued to Mexican nationals who are prohibited from holding non-domiciled CDLs (unless under DACA), and inadequate verification procedures. These violations triggered a preliminary determination of substantial noncompliance under 49 CFR 384.307, a process entirely separate from the stayed interim final rule.

California remains subject to a corrective action plan addressing these pre-existing violations. The court stay doesn’t change that. FMCSA’s November 13 guidance was explicit: states “subject to a corrective action plan” must maintain their pauses on non-domiciled CDL issuance until demonstrating compliance with pre-rule regulations.

Under 49 U.S.C. § 31312, FMCSA has authority to decertify a state’s entire CDL program if the state is found in “substantial noncompliance” with federal requirements. Decertification would prohibit California from issuing, renewing, transferring, or upgrading any commercial learner’s permits or commercial driver’s licenses, not just non-domiciled credentials, until FMCSA determines that the state has corrected its deficiencies.

The consequences would be immediate and severe. Every new driver in California’s CDL pipeline would freeze. CDL schools would halt operations. Testing would stop. Carriers would face weeks or months of disruption in recruiting new drivers. The ripple effects would devastate one of the nation’s most critical freight corridors.

FMCSA recently threatened Pennsylvania with decertification after an Uzbek terror suspect was found holding a Pennsylvania-issued CDL. The agency gave the state 30 days to respond and warned that failure to correct deficiencies could result in losing issuance authority entirely. California’s defiance appears far more egregious; the state is not merely failing to correct problems but actively moving to restore licenses that federal auditors determined were improperly issued.

Here’s where California’s gambit becomes particularly problematic. Commercial driver’s licenses aren’t purely state credentials; they’re federal credentials issued through a partnership with states. The Commercial Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1986 established minimum standards that all states must meet. When a state issues a CDL, other states recognize that credential based on the assumption that it was issued in compliance with federal standards.

If California reissues non-domiciled CDLs that federal auditors have determined don’t comply with federal regulations, those credentials may not be valid for interstate operation. A driver holding a California CDL issued in violation of federal requirements could face enforcement action in any other state, and carriers who dispatch those drivers could face liability exposure.

Under 49 CFR 384.405, decertification prohibits a state from performing any CLP or CDL transactions. Even short of full decertification, FMCSA could issue guidance that CDLs issued by a noncompliant state during the noncompliance period are not valid for interstate commerce. Other states could refuse to recognize California’s credentials. The Commercial Driver’s License Information System (CDLIS), which enables interstate verification, could flag California licenses.

The question isn’t whether FMCSA has authority to act; 49 U.S.C. § 31312 is unambiguous. The question is whether the agency has the political will to exercise that authority against the nation’s most populous state.

California’s argument rests on several claims. The state contends that the 17,000 licenses with mismatched expiration dates represent “clerical errors” rather than substantive violations. State officials point out that the work authorizations underlying these licenses remain valid; the DMV simply failed to align CDL expiration dates with employment authorization document expiration dates.

With the court stay in effect, California argues it can now correct those date mismatches and reissue compliant credentials. The state maintains that drivers with valid work authorization who pass the knowledge, skills, and medical tests should be able to obtain properly dated CDLs under pre-September 29 regulations.

This argument sidesteps FMCSA’s core findings. The agency didn’t merely identify date mismatches; it documented systemic failures in California’s verification procedures, including the issuance of licenses to Mexican nationals who were prohibited from holding non-domiciled CDLs. California’s October 26 response to FMCSA acknowledged finding 20,000 non-domiciled CDLs with expiration dates exceeding drivers’ lawful presence. Still, it refused to revoke them, arguing the state hadn’t violated federal regulations as they existed before the interim final rule.

FMCSA’s November 13 response rejected this interpretation as “erroneous,” noting that “the regulatory universe of non-domiciled CLPs and CDLs is premised on the basic notion that a non-domiciled driver’s commercial motor vehicle driving privileges cannot extend beyond that driver’s lawful presence in the United States.”

Behind the legal and regulatory frameworks are real people whose livelihoods hang in the balance. Many of the affected 17,000 drivers are Sikh men who fled persecution in India and sought asylum in the United States. The transportation and logistics industry has been a major employer for this community; approximately 150,000 Sikhs work in trucking nationwide, with California hosting the largest U.S. Sikh population.

Amarjit Singh, a 41-year-old truck owner-operator in Livermore, represents the personal dimension of this crisis. His work authorization extends through 2029. He invested $160,000 in his truck in 2022, faces $4,000 monthly payments, and supports two young children. When Singh heard California would reissue his license, he prayed in gratitude. His wife cried.

“It’s going to save my life, and it’s going to save my business,” Singh told KQED.

Singh’s relief may be premature. If FMCSA determines that California’s reissued licenses don’t comply with federal regulations, Singh and thousands of drivers like him could face the same uncertainty all over again, potentially worse, if other states refuse to recognize California credentials or if FMCSA moves toward decertification.

This confrontation unfolds against a backdrop of intense political conflict between California and the Trump administration. Governor Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a leading Democratic opponent of federal immigration enforcement. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy has made non-domiciled CDL enforcement a signature initiative, personally announcing enforcement actions against California and warning of consequences.

When a California asylum seeker named Jashanpreet Singh crashed his truck on I-10 on October 21, killing three people, Duffy issued a “bombshell report” directly blaming California for breaking federal law. “My prayers are with the families of the victims of this tragedy,” Duffy said. “It would have never happened if Gavin Newsom had followed our new rules. California broke the law and now three people are dead.”

California countered that the Jashanpreet Singh case involved the automatic removal of an age-based restriction, not a discretionary upgrade. The state argued it had complied with the then-existing regulations. FMCSA rejected this defense.

The political stakes guarantee that neither side will back down easily. For the Trump administration, allowing California to defy federal CDL requirements would undermine its entire enforcement framework. For California, capitulating would validate what advocates call a “contrived emergency” targeting immigrant workers.

FMCSA faces a choice. The agency can accept California’s interpretation that the court stay permits license reissuance, effectively allowing the state to sidestep compliance requirements. Or it can enforce its position that California remains under corrective action and must demonstrate compliance with pre-rule regulations before resuming non-domiciled CDL issuance.

The enforcement tools are clear. FMCSA can withhold federal highway funding, up to $75.5 million in fiscal year 2027, with amounts doubling in subsequent years. The agency can issue a final determination of substantial noncompliance. And it can decertify California’s CDL program entirely, prohibiting the state from issuing any commercial driving credentials until deficiencies are corrected.

Given the current political dynamics, FMCSA moving toward decertification seems more likely than backing down. The agency has already threatened to decertify Pennsylvania for less egregious violations. Texas, Colorado, South Dakota, and Washington have all received compliance warnings. If California can openly defy federal requirements without consequence, the entire federal-state CDL partnership becomes meaningless.

For carriers operating in California or employing drivers with California non-domiciled CDLs, the uncertainty continues. The safest course is to monitor FMCSA guidance closely, document immigration status verification for all non-domiciled drivers, and prepare for the possibility that California credentials face additional scrutiny or rejection in other states.

Underlying this entire controversy is a question the D.C. Circuit Court’s stay didn’t resolve: Who ultimately controls commercial driver licensing standards in the United States?

The Commercial Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1986 established federal minimum standards that states must meet. But states actually administer licensing programs. When a state believes federal standards are wrong, whether procedurally flawed, as the court found with the interim final rule, or substantively discriminatory, as advocates argue, what mechanisms exist to resolve the conflict?

The funding withholding and decertification provisions in 49 U.S.C. § § 31314 and 31312 provide federal enforcement tools. But using those tools against California would create massive disruptions to interstate commerce and potentially strand hundreds of thousands of drivers. The practical consequences may constrain federal enforcement regardless of legal authority.

Meanwhile, 17,000 drivers wait to learn whether the licenses California plans to reissue will actually let them work. Carriers wait to learn whether those credentials will be recognized outside California. And the rest of the trucking industry watches to see whether federal CDL standards mean anything at all when a state decides to ignore them.

The post California Defies Federal Pressure, Plans to Reissue 17,000 Non-Domiciled CDLs appeared first on FreightWaves.