Otto Frank’s poignant pleas to save his family before they famously went into hiding along a canal in Amsterdam. A photograph of Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher chatting nonchalantly before a crowd of starstruck onlookers at Grossinger’s resort in the Catskills.

Those prized possessions are in the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, celebrating its 100 anniversary. The documents, photographs and objects record modern Jewish history and culture, from the religious to the comic, from the horror of the Holocaust to the joys of Irving Berlin sheet music.

YIVO was established in 1925 in Vilna, then in Poland, now Lithuania, with the support of such luminaries as Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud. Today headquartered in New York City, it is an institution that represents the wholeness of the Jewish people, said its executive director, Jonathan Brent.

“There are Zionistic works, there are anti-Zionistic works,” he said. “There are materials about anarchism, there are materials about Bolshevism, there are materials about immigration, atheism, the entire gamut of Jewish life.”

That is not by accident, Brent said. Its founding ethos was that every part of Jewish life was important.

To mark the milestone, YIVO selected 100 items from its archives to include in a book, “100 OBJECTS from the Collection of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.”

“Archives and libraries are powerful places,” Stefanie Halpern, the archives director, writes in the introduction. “They can create history or erase it based merely on what they choose to collect and how and to whom they make materials available for use.”

Here’s a look at a few of the objects in the archives.

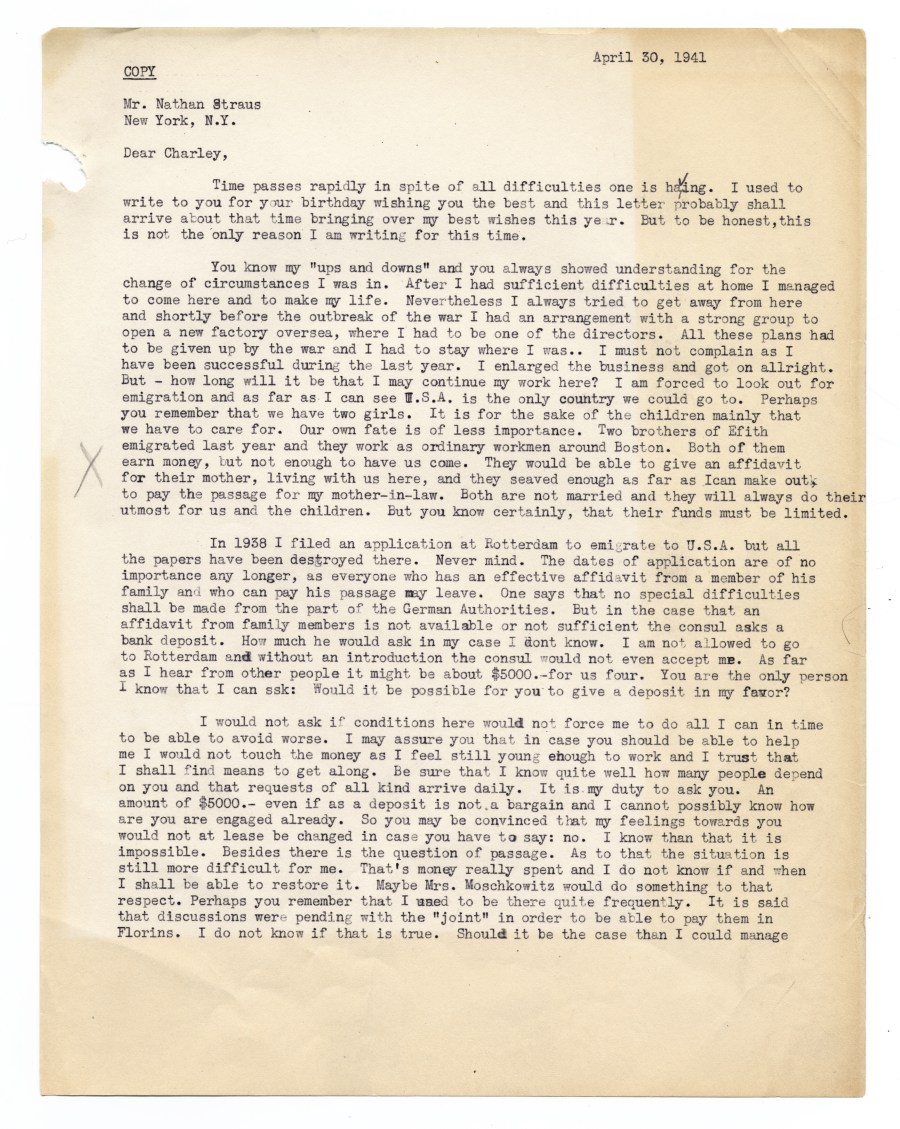

Otto Frank’s appeals for help

Anne Frank is among the best known victims of the Holocaust, a Jewish teenager who on her thirteenth birthday received a diary in which she would record the family’s two years hidden in an annex of her father’s business along a canal in Amsterdam. Papers from her diary were preserved even as she and the others in hiding were discovered and arrested in August 1944, and after she died early the next year from typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

What are less well known are her father’s tragically unsuccessful efforts to bring his family to safety in the United States. In 1941, Otto Frank wrote to Nathan Straus, Jr., the son of a co-owner of Macy’s department store, and his friend from college days some 30 years earlier in Heidelberg, Germany, asking for financial help for a deposit for their travel.

“I am forced to look out for emigration and as far as I can see U.S.A. is the only country we could go to,” Frank wrote to Straus, known also as Charley. “Perhaps you remember that we have two girls. It is for the sake of the children mainly that we have to care for. Our own fate is of less importance.”

The letters and other documents, most dating from April 30, 1941, until December 11, 1941, were discovered in YIVO’s archives in 2005 by a volunteer helping to index the files.

Nathan Straus, Jr., and his wife, Helen, made appeals on behalf of the Franks, according to YIVO. But the new restrictions on immigration were insurmountable, and Otto Frank wrote, “The only way to get to a neutral country are visas of others States such as Cuba.”

In the end, Cuba issued one visa in the name of Otto Frank. Ten days later, when Germany declared war on the United States, it was canceled.

Otto Frank was the sole member of the family to survive the Holocaust. Anne’s sister, Margot, died with her in the Bergen-Belsen camp. Their mother, Otto Frank’s wife, Edith, died from starvation in the Auschwitz-Birkenau death and concentration camp.

The family’s hiding place in Amsterdam has been turned into a museum. More than 30 million copies of Anne Frank’s diary have been sold.

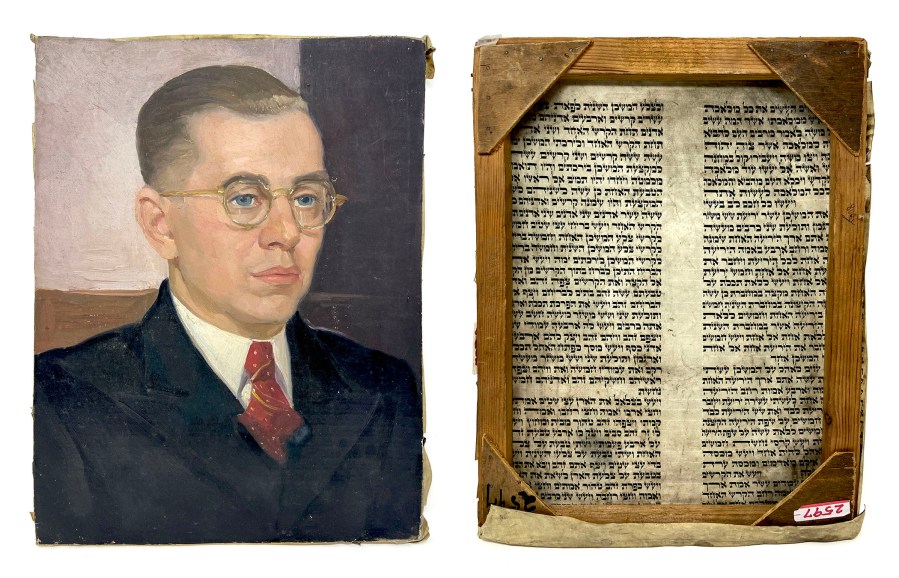

A Nazi portrait (on a desecrated Torah scroll)

One of the more bizarre items in the YIVO archives is this portrait of a Nazi painted on a Torah scroll.

It is believed to be of Arthur Seyss-Inquart, an Austrian official who shared responsibility for the deportation of Dutch Jews to death camps. In a speech in 1941, he said, “We will smite the Jews where we meet them and whoever goes along with them must take the consequences.”

After the war, he was indicted for crimes against humanity, and at the Nuremberg trials, he was sentenced to death. He was hanged in 1946.

The oil painting was found by chance in a Vienna flea market by an American couple from Pennsylvania, Shirley and Mortimer Kadushin. Mortimer Kadushin served in the U.S.Army during World War II and himself was the target of antisemitic discrimination.

Seyss-Inquart looks like an ordinary bureaucrat, Brent said, a tax official or bank teller, except that the portrait appears on a piece of parchment ripped from a Torah, desecrating the text. The painting encapsulates the way the Nazis treated murdering European Jews — and destroying their culture and their God — as an administrative affair, Brent said.

“It was really an act of tremendous, lethal hatred that inspired it, and which you have to somehow connect with that very banal expression,” Brent said.

A manuscript hand-written by a Rothschild

Before the Rothschilds became Europe’s most famous banking family and their name synonymous with great wealth, there was 12-year-old Amschel Moses Rothschild, copying a tractate from the Talmud dealing with Jewish monetary law, perhaps as part of his scribal training as a bar mitzvah student.

He produced the tiny manuscript between 1721 and 1722, ornately decorated and passed down through generations of the Rothschild family for more than a century. He later worked as a money changer in Frankfurt, Germany, and a silk cloth trader and it was his son Mayer Amschel Rothschild who went on to found the Rothschild banking dynasty.

The Rothschild family has had long ties with YIVO, and in 2012, YIVO honored a sixth-generation descendent of Mayer Amschel Rothshild, Baron David de Rothschild.

Vibrant dolls outfitted in an Italian camp

A colorful collection donated to YIVO in 1989 consists of what appear to be the famous Italian-made Lenci dolls, constructed of wool felt, known for their heat pressed faces and painted features, and dressed in cotton, felt, silk and velvet.

The 17 dolls wear the traditional clothes of Siena’s contradas or districts, that are represented during a costume parade that precedes a twice-a-year horse race, the Palio di Siena, Halpern, the director of the YIVO Archives, points out in “100 Objects.”

Why are the dolls, purchased sometime in the late 1940s, in YIVO’s archives? All of the clothes were made by children living in a displaced persons camp in Florence after the end of World War II. Some 250,000 Jewish survivors of the Holocaust stayed in displaced persons camps in Italy, Germany and Austria, 50,000 of them in the 35 camps set up in Italy between 1945 and 1948.

“The dolls from the DP camps are extraordinary expressions of hopefulness about the future, about children playing, the idea that children actually could play,” said Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director. “These were children largely born in the camps or somehow saved during the war, and they had hope for the future. And that’s what you see in those dolls.”

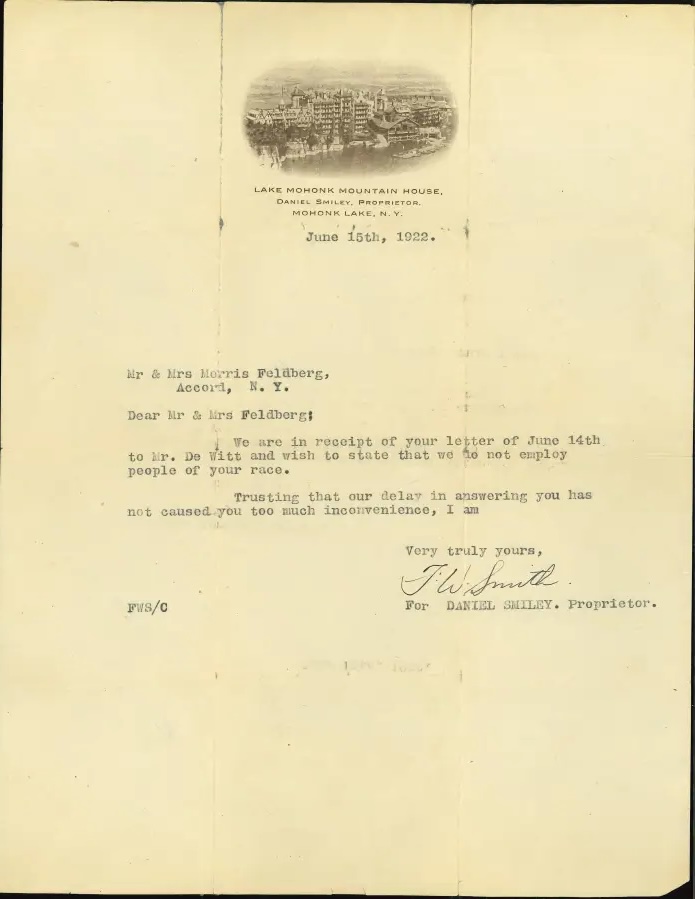

Antisemitic rejection from a New York resort

A letter from Mohonk Mountain House highlighting the antisemitism in New York in the 1920s. (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

A letter from Mohonk Mountain House highlighting the antisemitism in New York in the 1920s. (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

The letter to the couple from Accord, New York, seeking employment at the Lake Mohonk Mountain House is brief in its rejection, only two paragraphs, but devastating.

“We are in receipt of your letter of June 14th to Mr. De Witt and wish to state that we do not employ people of your race,” reads the first of the paragraphs, written by a J.W. Smith for Daniel Smiley, proprietor.

Mohonk Mountain House is a Victorian castle 90 miles north of New York City. The resort dates to the 1869, when Albert Smiley bought a 10-room inn by a glacial lake, and renovated and expanded it. Today, the Smiley family still owns and runs the property, on the Shawangunk Ridge.

At the time that Morris Feldberg and his wife applied for work there in 1922, antisemitism was flourishing across the United States. In Michigan, Henry Ford was engaged in an antisemitic campaign in his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, publishing articles about a supposed international Jewish conspiracy based on the scandalous antisemitic forgery, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Articles drawn from the newspaper became the volumes of “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem.”

“They’re turned down, and the reason for their being turned down is very interesting,” Brent said. “It’s not that we don’t employ people of your religion. It’s that we do not employ people of your race. And therefore what this reflects is the race thinking and the racial philosophies that were then dominating the United States of America, that were part and parcel of the eugenics movement and what has become known as white supremacy.”

The letter from Lake Mohonk Mountain House, dated June 15, 1922, went on to say, “Trusting that our delay in answering you has not caused you too much inconvenience.”

The nearby Catskill Mountains became known for Jewish vacation spots in the early to the 20th century, a result of pervasive antisemitism that also gave rise to the Jewish Vacation Guide. Like the Green Book that followed and which was written for Black Americans, the Jewish Vacation Guide directed Jewish travelers to places where they would be safe, initially to farmhouses that took in boarders and later resorts.

Asked about the letter, the current president of the Mohonk Mountain House said that the Smiley family could find no evidence of a discriminatory policy toward staff or guests in business records from more than 100 years ago.

“Our ancestors were devout Quakers, believing in the equality of all people, and were deeply concerned about the social inequities of their time,” the president, Eric Gullickson, one of the fifth generation of the Smiley family, said in an email. “They dedicated their lives towards efforts to improve the human condition.”

He said employees working in the front office signed all letters for Daniel Smiley.

“We regret that 103 years ago an employee of Mohonk took this action on behalf of the Smiley family,” he said. “This has never been a policy in Mohonk’s 156-year history — not then, nor is it now, a policy of the Smiley family or Mohonk Mountain House.”

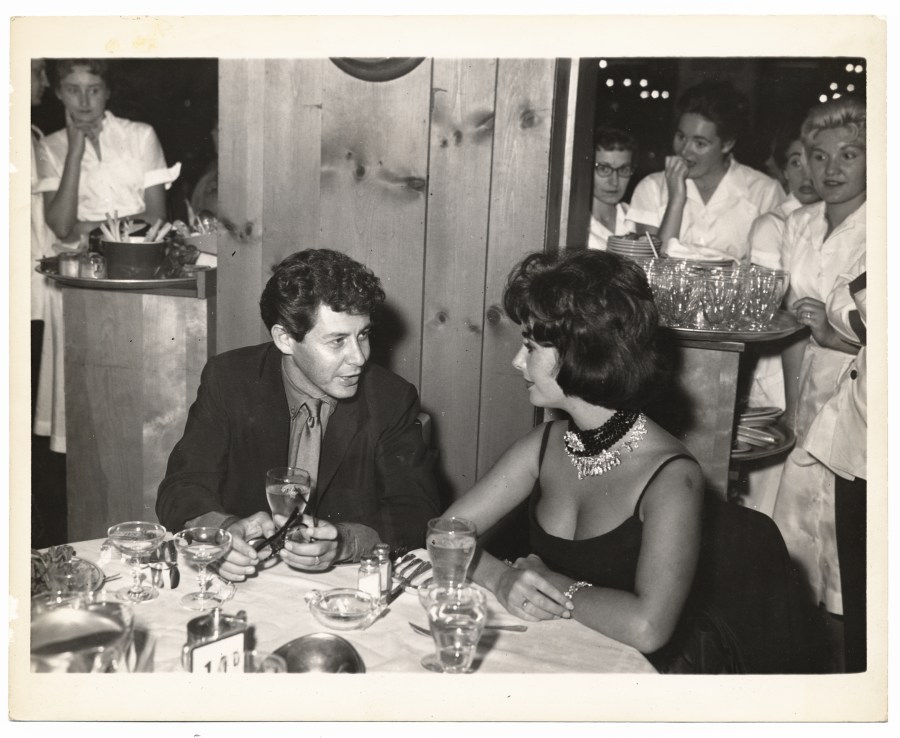

Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher and a crowd of admirers

The photograph was taken at Grossinger’s hotel, probably in 1959, the year Elizabeth Taylor married singer Eddie Fisher. A group of waitresses captivated by the famous couple crowd in the doorways.

Grossinger’s was among the best known of the Catskills’ Borscht Belt resorts, which were known for their entertainment, from musicals to stand-up routines.

“It was the New York City escape to which all other Catskills operations—indeed, lodgings throughout America—aspired,” the Smithsonian magazine wrote in 2015.

This was Taylor’s fourth marriage. Fisher and Taylor’s third husband, Mike Todd, were best friends and after Todd died in a plane crash, she kept him alive by talking about him with Fisher, she said. She liked Fisher, but never loved him, she admitted later.

“As a matter of fact, I don’t remember too much about my marriage to him, except it was one big, frigging awful mistake,” she says in a 2024 HBO documentary, ‘Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes.’ “I knew it before we were married and didn’t know how to get out of it.”

Fisher was a regular at Grossinger’s, and had married his previous wife, Debbie Reynolds, there, said Eddy Portnoy, YIVO’s senior academic advisor and director of exhibitions.

An obituary of one of the resorts’ founders, Jennie Grossinger, that appeared in The New York Times noted that Eddie Fisher was an unknown singer at the hotel when he was discovered by Eddie Cantor, then a guest. Fisher “started on the road to glory from the hotel,” according to the obituary.

“Elizabeth loved coming up to Grossinger’s because she could relax and no one would bother her,” Jackie Horner, a dancer who knew her, told the Times Herald-Record in 2011.

A one-of-a-kind menorah

The unusual glass menorah in YIVO’s archives is actually a water pipe for smoking cannabis or a bong. It was created by David Daily, the owner of a company called GRAV, and the artist Charlie Glass, originally for celebrating Hanukkah with Daily’s family but which he later put into production. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

The unusual glass menorah in YIVO’s archives is actually a water pipe for smoking cannabis or a bong. It was created by David Daily, the owner of a company called GRAV, and the artist Charlie Glass, originally for celebrating Hanukkah with Daily’s family but which he later put into production. (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

The unusual glass menorah, with eight bowls and a place for the highest candle, is actually a bong or a water pipe for smoking cannabis.

It was created by David Daily, the owner of a company called GRAV, which makes pipes and bongs, and the artist Charlie Glass. It was intended for celebrating Hanukkah with Daily’s family — the holiday of lights that commemorates the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem, when lamp oil meant for only one day lasted eight instead.

But Daily later put it into production.

It is one of the newer additions to YIVO’s archives, and part of a collection on Jews and cannabis. Archeological discoveries in Israel have shown that it was used by ancient Israelites in religious rituals, according to Portnoy.