Time is running out! Your donation to Berkeleyside can be matched—but only until midnight on Dec. 31. Give now and double your support of our nonprofit journalism.

A path wends up the ivy-colored hills of John Hinkel Park. Credit: Sara Martin for Berkeleyside

A path wends up the ivy-colored hills of John Hinkel Park. Credit: Sara Martin for Berkeleyside

Editors’ note: This week we’re republishing some of our favorite stories of 2025. This story was first published on Oct. 1.

On a recent sunny Sunday, a troupe of actors was rehearsing “The Taming of the Shrew” at the amphitheater in John Hinkel Park.

Nearby, a group of young children piled onto the playground’s tire swing and climbed its wooden structures, while their parents ate bagels and sipped coffee and chatted about the upcoming school year.

Parks of Berkeley

This story is part of an ongoing series exploring the history and current life of several of the city’s most notable parks.

Other parkgoers meandered along the trails weaving through the park’s steep ivy-covered hills, shaded from the late summer sun by redwoods, bay laurels and California buckeyes. The gentle flow of Blackberry Creek could be heard burbling down the hill.

Standing next to the old stone fireplace, you could almost imagine you were at summer camp.

Such is the magic of John Hinkel Park, a 4.2-acre park nestled near the bottom of the Berkeley Hills on Somerset Place just off of Arlington Avenue and flanked on two sides by the winding San Diego Road.

“It’s a nice mix of natural landscape and terrain and also some playground elements that are really great for the kids,” said Saimon Kos, who lives in Kensington and was at the park with a group of families from Bay Area Kinderstube, a German-language preschool based in Albany.

And because of the park’s layout “it’s easy to keep track of the older kids as they explore the space and tire themselves out,” he said.

An aerial view of John Hinkel Park on July 20 during a performance of “Cymbeline.” Credit: Jonathan Hidalgo for Berkeleyside

An aerial view of John Hinkel Park on July 20 during a performance of “Cymbeline.” Credit: Jonathan Hidalgo for Berkeleyside

Some of those kids were lured into watching the Shakespeare rehearsal, a production of the Actors Ensemble of Berkeley, a 68-year-old theater company that produces two shows a year at the park.

The park is “perfect for Shakespeare,” said Stanley Spenger, a longtime actor and theater director who served as board president of the Actors Ensemble for a decade. “It’s kind of an ‘As You Like It’ dream world, green world.”

“I didn’t even know this park existed,” said Isabella Shipman, a double music and theater major at UC Berkeley who is part of the “Taming of the Shrew” cast.

It’s a familiar refrain of people encountering the park, which is listed among 510 Families’ Secret Spots and a waypoint on Charles Fleming’s “Secret Stairs: East Bay” walking guide.

Park was a bequest from one of Berkeley’s wealthiest men

John Hinkel Park on July 24. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

John Hinkel Park on July 24. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

The park was gifted to the city in 1919 by John Hinkel and his wife, Ada.

At the time, Hinkel was one of Berkeley’s richest men, according to a 1949 article in the Berkeley Gazette. The son of Dutch immigrants, Hinkel was born in Galena, Illinois, in 1850 and made his way to San Francisco in the early 1860s, where he eventually became a banker. He soon amassed a fortune in stocks, real estate and oil and the Hinkels moved to Berkeley at the turn of the century, throwing lavish parties at their home on Channing Way.

The oak woodlands of the Berkeley Hills had once been a gathering place for generations of Ohlone, who came each spring and set up base camps, processing plants, meat and fish in bedrock mortars. The coast live oaks that still grow on the park’s grassy hillsides would have been a source of acorns, a staple Ohlone food.

By Hinkel’s era, the hills had become a locus of real estate speculation, with city streets paved with material from Ohlone shellmounds and the Mason-McDuffie Company building out the Northbrae subdivision as a “middle-income” neighborhood — in contrast with the ritzier Claremont district, though Black and Asian people were barred from buying homes in both areas.

Hinkel bought up property throughout Berkeley, including the site of the park which now bears his name, “a seven-acre canyon, thick with underbrush and alive with poison oak,” according to the Gazette.

He made many changes to the land before handing over the deed to the city, including laying out walks and trails, clearing vegetation and building a playground, clubhouse and fireplace, at “an expenditure of many hundreds of dollars in development,” according to John Gregg, who served as president of the park commission at the time.

A supporter of the Boy Scout movement, Hinkel had allowed the scouts to camp on the land before giving it to the city and dedicating the park “in appreciation of the Boy Scouts’ services to the nation during the First World War,” according to a City of Berkeley Landmark plaque.

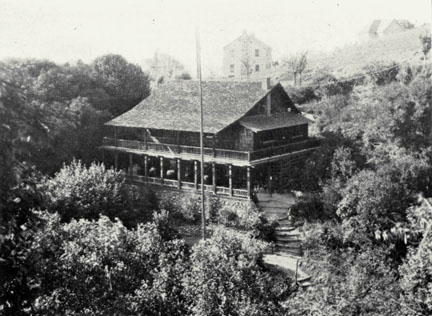

A photo appearing in the May 23, 1953, Berkeley Daily Gazette. Courtesy: Newspapers.com

A photo appearing in the May 23, 1953, Berkeley Daily Gazette. Courtesy: Newspapers.com

Gregg, who was also a noted UC Berkeley landscape architecture professor, helped design the park with city landscape engineer Carl F. Biedenbach.

Hinkel wanted the park to be “a natural space where the native flora would be retained and enhanced rather than being replaced with artificial plantings,” according to Susan Dinkelspiel Cerny, who wrote about the park in a 2002 article published by the Berkeley Daily Planet.

One particular native plant was decidedly not welcome, a plant that has long been the bane of landscape architects and hikers in the area: poison oak. Removing the poison oak was not easy. The Gazette likened it to “evicting armed squatters from an early California mining claim.”

Hinkel’s former hunting lodge is just up the road from the park, at 42 Somerset Place.

“This house and others were built a hundred years ago as summer vacation places,” said Forrest Mozer, who’s lived across the street from the park since 1967. “People from San Francisco would make the long trek across the Bay to their summer house.”

Today, the home’s valued by Redfin at $2.2 million, a little over par for a neighborhood that’s now among the city’s most affluent and still one of its least racially diverse.

Performance has been at the heart of John Hinkel Park’s appeal for over 90 years

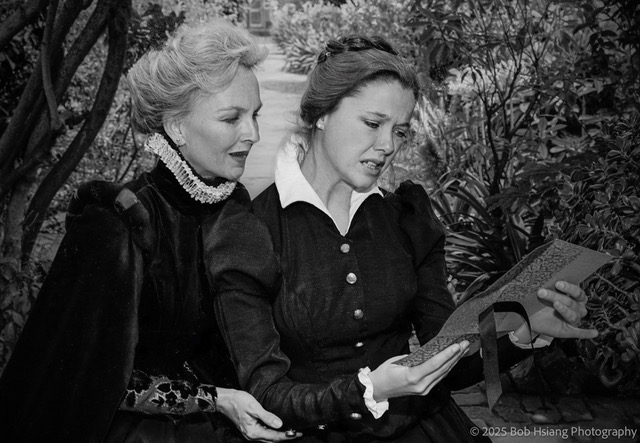

Annette Bening, at right, now a Hollywood star, as Helena in a 1982 Berkeley Shakespeare Festival production of “All’s Well That End’s Well” at John Hinkel Park. Katherine Conklin, as the Countess of Roussillon, is at left. Credit: Bob Hsiang

Annette Bening, at right, now a Hollywood star, as Helena in a 1982 Berkeley Shakespeare Festival production of “All’s Well That End’s Well” at John Hinkel Park. Katherine Conklin, as the Countess of Roussillon, is at left. Credit: Bob Hsiang

The heart of the park these days is the stone amphitheater, which was built in 1934 by the Civil Works Administration, a New Deal program that provided jobs for millions of Americans during the Great Depression. It was designed by Vernon Dean, who also designed Berkeley’s Rose Garden, and attracts visitors from across the city and beyond.

Over the years the park has held hundreds of productions, including two “operas” from the Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company, which held shows in the late 1960s featuring “stirring coloured lights, bare-breasted dancers waving grain stalks, silver face paint, and silk sheets used to symbolise the River of Life,” according to Far Out Magazine. The company did not last long at the park due to neighbors’ complaints about their “wailing and crashing racket.”

In 1974, the Emeryville Shakespeare Company began staging productions at the park. The troupe soon renamed itself the Berkeley Shakespeare Festival, and later the California Shakespeare Theater, better known as Cal Shakes, which eventually outgrew the park’s amphitheater and moved to Orinda in 1991. The nonprofit closed last year due to financial issues.

Opening day of “The Taming of the Shrew,” on Aug. 16. Credit: Kirsten Yamaguchi

Opening day of “The Taming of the Shrew,” on Aug. 16. Credit: Kirsten Yamaguchi

In the early days at John Hinkel Park, the company would serve mulled wine during intermission, according to Jane Goodwin, an Actors Ensemble board member who performed at the park with the Berkeley Shakespeare Festival.

“Berkeley literary people love Shakespeare,” she said. “They’d come with their scripts and would read along with us and probably make sure we were doing it right.”

Annette Bening performed in multiple productions at the park, including the title role in “Romeo and Juliet,” which Spenger recalls as “the best Juliet I’ve ever seen live on stage.”

The park’s historic amphitheater, built by the Civil Works Administration in 1934, was renovated in 2022, with overgrown weeds removed and repairs made to the masonry. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside

The park’s historic amphitheater, built by the Civil Works Administration in 1934, was renovated in 2022, with overgrown weeds removed and repairs made to the masonry. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside

The former clubhouse was used for costume storage and served as the actors’ dressing rooms during production, before problems with the foundation led the clubhouse to begin sliding down the hill, according to Jerome Solberg, who also serves on the Actors Ensemble board and is something of a historian of staged productions at the amphitheater. The clubhouse was gutted by fire in 2015 and removed.

Other performance groups that have used the park include the Berkeley Folk Dancers, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Shotgun Players, Inferno Theatre, and Women’s Will Theater Collective, an all-female Shakespeare company.

Park was dramatically upgraded in 2022

The playground at John Hinkel Park, built on a former asphalt lot. Credit: Ximena Natera/Berkeleyside

The playground at John Hinkel Park, built on a former asphalt lot. Credit: Ximena Natera/Berkeleyside

The park recently underwent an eight-year, $1 million renovation project, completed in 2022. The renovations included refurbishing the amphitheater seating and building a path to allow for wheelchair access.

The amphitheater’s concrete “stage” was revamped, in consultation with Actors Ensemble, including the installation of holes that can be fitted with metal poles to support the theater company’s fabric sets. And the city built a concrete pad near the stage so the theater troupe could install a storage container.

But one of the most dramatic parts of the renovation was moving the playground from its former site on a grassy hillside, where tree roots made construction difficult, and steep curves raised concerns about ADA access — not to mention an uproar about the proposed use of artificial turf — to right next to the amphitheater. The playground’s structures are made of redwood salvaged from the fire-gutted clubhouse, giving the park the natural feel that Hinkel envisioned for it, and that parkgoers love.

The park’s old clubhouse — gutted by fire in 2015. Credit: Diane Phillips/Historical Marker Database

The park’s old clubhouse — gutted by fire in 2015. Credit: Diane Phillips/Historical Marker Database

Picnic Site No. 1 is the former site of the park’s clubhouse, which was gutted by fire in 2015. Credit: Nathan Dalton

Picnic Site No. 1 is the former site of the park’s clubhouse, which was gutted by fire in 2015. Credit: Nathan Dalton

The new playground brings a regular injection of youth to a neighborhood where the median age is 56, making it one of the oldest neighborhoods in Berkeley, according to U.S. Census data.

Mozer said the playground is “well used now and certainly well appreciated.”

The park’s Scout Hut, located on the north edge of the park, was moved to the location in 1938 from Garfield Junior High School (now Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School), according to the website of Troop 19, which calls the hut home. The hut is now in disrepair, with plans for improvements, including the potential construction of a bathroom, kitchenette and exterior deck. Credit: Diane Phillips/Historical Marker Database

The park’s Scout Hut, located on the north edge of the park, was moved to the location in 1938 from Garfield Junior High School (now Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School), according to the website of Troop 19, which calls the hut home. The hut is now in disrepair, with plans for improvements, including the potential construction of a bathroom, kitchenette and exterior deck. Credit: Diane Phillips/Historical Marker Database

The new placement of the playground is both a blessing and a curse for the actors performing at the amphitheater. On the one hand, if kids get bored and restless watching Shakespeare, their parents can shoo them off to the playground, instead of having to leave the play altogether.

But on the other hand, the sound of the children playing can make it hard to hear the actors.

But this is part of the richness of John Hinkel Park, a place for Boy Scout troops and acting troupes, a place where you’re as likely to find a lively production of a play as a lone person practicing tai chi, a place where piñatas are routinely smashed at children’s birthday parties, and a place of nature and respite.

Related stories

Revamped amphitheater, new picnic area open at John Hinkel Park

July 18, 2022July 20, 2022, 9:45 a.m.

Free Shakespeare returns to John Hinkel Park in North Berkeley

June 2, 2023June 2, 2023, 2:02 p.m.

Fire guts abandoned clubhouse in John Hinkel Park

January 19, 2015Oct. 4, 2022, 1:20 a.m.

Let’s be real …

These are uncertain times. Democracy is under threat in myriad ways, including the right of a free press to report the truth without fear of repercussions.

One thing is certain, however: Berkeleyside was built for moments like these. We believe wholeheartedly that an informed community is a strong community, so we’re doubling down on our mission of reporting the stories that empower and connect you when it matters most.

If you value the news you read in this article, please help us keep it going strong in 2026.

We’ve set a goal to raise $180,000 by year-end and we’re counting on our readers to help us get there. And a bonus: Any gift you make will be matched through Dec. 31 — so $50 becomes $100, $200 becomes $400. Will you make a donation now in support of nonprofit journalism for Berkeley?

Tracey Taylor

Co-founder, Berkeleyside

“*” indicates required fields