The magnitude of San Francisco’s homelessness problem — more than 8,300 unhoused people based on the most recent count, and a chronic shortage of housing — requires priorities. Who’s most vulnerable? Who’s ready to be matched with a vacant apartment? Who needs extra services?

It gets complicated fast. People have physical and mental health needs or struggle with drugs or alcohol. A small percentage have kids. Sometimes there are language barriers.

The city’s priority system for housing, known as coordinated entry, went into effect in 2018. Only three years later, city officials were talking about an overhaul.

But many of the fixes have yet to take shape, spending years in committees. Meanwhile SF’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH), which has a $677 million budget this year, is now working under a new mayor. Daniel Lurie, elected by voters dissatisfied with public safety and the overdose crisis, wants more focus on drug treatment and sobriety in the city’s portfolio of temporary and permanent housing.

In this two-part series, The Frisc examines how San Francisco moves people from the streets to homes: how coordinated entry works, why it’s flawed, and how it’s supposed to be fixed.

However, making changes is now more complicated. Any city or county that wants U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds for homelessness services must have a coordinated entry system. San Francisco has received about $60 million annually in recent years, according to HSH deputy director for communications and legislative affairs Emily Cohen.

The access point run by Episcopal Community Services at 123 10th Street shares a building with modern and vintage scooters. (Photo: Ayla Burnett)

The access point run by Episcopal Community Services at 123 10th Street shares a building with modern and vintage scooters. (Photo: Ayla Burnett)

But the Trump administration’s new rules for funding and its unpredictability are creating deep uncertainty and even more delay. San Francisco risks losing those federal grants — nearly 10 percent of its homelessness budget — if it runs afoul of the White House.

We will examine the Trump effect more in Part 2 of this series. First, we’ll look how coordinated entry works — or, as critics say, how it doesn’t.

Step 1: Problem-solving and questions

Coordinated entry is designed to be a funnel. Roughly 10 percent of people who start the process get housing through HSH.

There’s not much extra capacity. Housing for formerly homeless people has a vacancy rate in the single digits. The funnel will remain narrow unless that housing stock grows — and outpaces the growth of the homeless population.

If a homeless person in San Francisco wants a roof over their head, it takes some effort, patience, and a lot of luck. There are four main steps.

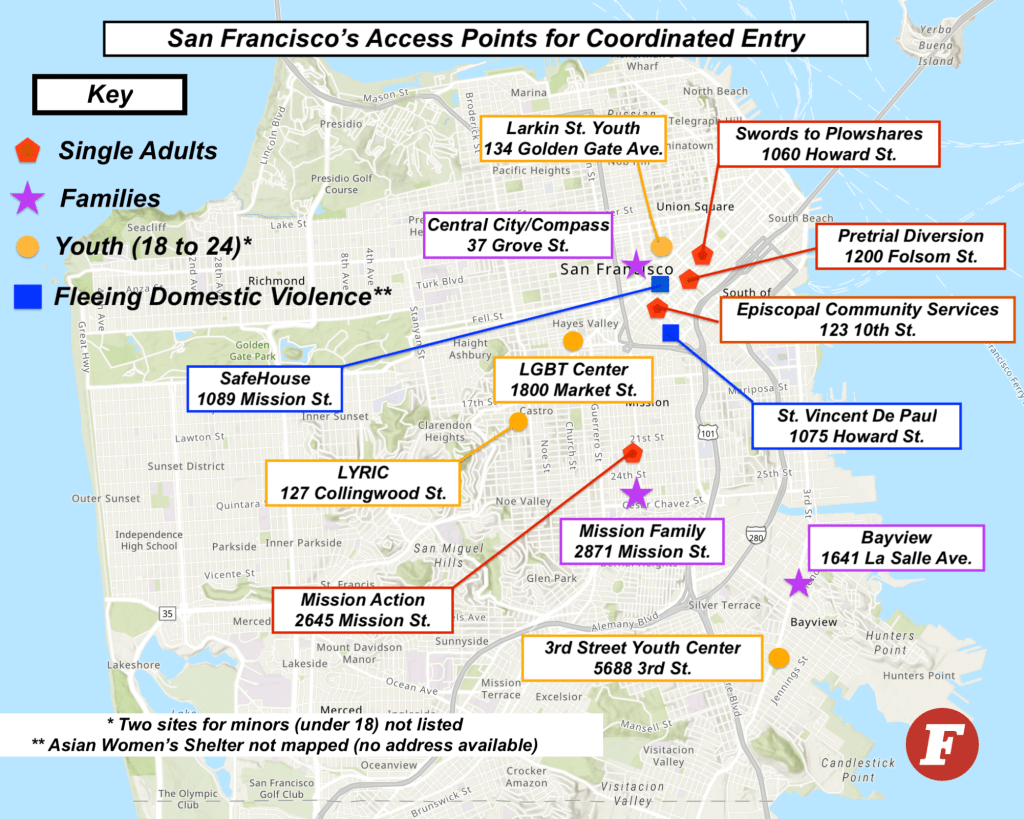

The first is to find one of the city’s access points, all hosted by nonprofit service providers. Four are for single adults, three are for families, six are for people under 25, and three are for people fleeing violence. HSH also employs mobile workers to sign up people on the street.

Sources: Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing; Open Data SF; The Frisc.

Sources: Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing; Open Data SF; The Frisc.

At Episcopal Community Services’ access point on 10th Street in South of Market, the front desk attendants greet visitors with water, snacks, and an intake form. After filling out the form, visitors meet with a “problem solver” for a private conversation.

The problem solver asks if the visitor needs something other than an apartment. Some examples are a bus ticket home, a job search, or mediation with a friend or family member with a place to stay.

If there’s no other option for stable housing, the visitor then goes through an assessment — a questionnaire to determine the person’s eligibility for city housing.

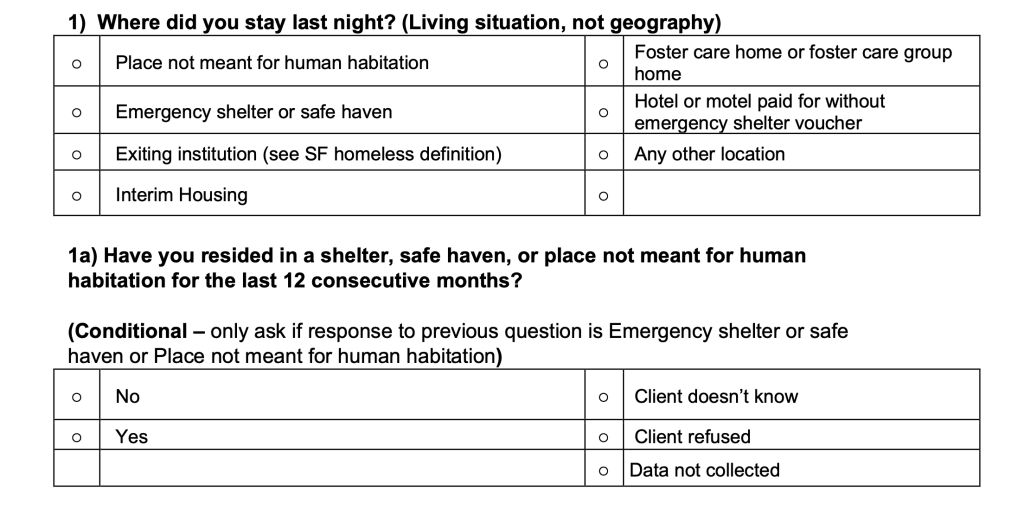

The questions start with logistics — Where did you stay last night? — then become more personal: How long have you been homeless? Are you experiencing physical or sexual violence? Are you pregnant?

Since only about 10 percent of visitors can expect to receive housing, the questions are too intrusive, say some critics, including Megan Rohrer, co-chair of the Local Homeless Coordinating Board, which oversees SF’s spending of federal homelessness funds.

The coordinated entry questionnaire for single adults starts with more general questions (above) and gets increasingly more detailed. Critics say some of the questions are too intrusive.

The coordinated entry questionnaire for single adults starts with more general questions (above) and gets increasingly more detailed. Critics say some of the questions are too intrusive.

But without the answer to these questions, HSH says it’s difficult to know what kind of housing, if any, someone needs.

Step 2: The score

Not everyone gets through the questionnaire. But if they do, a computer program reads it and issues a score from 0 to 160, which indicates eligibility to join a housing wait list. The ranking is fluid; Rohrer likens it to a hospital emergency room. If you have a bad cold, and someone comes in missing a limb, you’re not going to be seen first: “If you think you’re close, you aren’t necessarily if next month all the points change.”

HSH’s Cohen says the average wait time for an offer is 108 days. Then there’s usually more waiting — a month or more — to actually move in.

The rooftop garden of The Margot, one of dozens of apartment buildings in San Francisco’s permanent supportive housing portfolio. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

The rooftop garden of The Margot, one of dozens of apartment buildings in San Francisco’s permanent supportive housing portfolio. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

One factor in a person’s score is “acuity” — the severity of their problems.

Erica Kisch, CEO of Compass Family Services, which operates an access point for families, says “prioritizing the neediest families makes sense in one way,” but the risk is that families who aren’t the neediest won’t get services, then find themselves “more desperate.”

“We need resources for all families,” says Kisch.

Single adults make up the majority of SF’s homeless population, and the same scarcity of resources apply to them.

Step 3: Referral

Episcopal (ECS), Compass, and other access point operators do the intake, the problem solving interview, and the questionnaire. But HSH makes housing referrals. ECS chief program officer Chris Callandrillo said he doesn’t know how the city determines someone’s eligibility: “We don’t know that [the process] is bad, we just know that it’s not transparent.”

(The other nonprofit that runs a general access point for single adults, Mission Action, did not respond to multiple requests for interviews.)

The people who get the golden ticket of a housing referral will get one of two kinds of housing. One is permanent supportive housing, typically in city-owned buildings or SROs that have some health care and other services on site.

The other is rapid rehousing, a private-market rental subsidy. It’s more of a temporary arrangement; the value of the subsidy decreases over time. These units tend to go to families with a score between 90 and 114, meaning they don’t necessarily need the extra services that come with supportive housing.

(Families can also access temporary shelter through coordinated entry, while single adults can’t. And the likelihood of families getting an offer for supportive housing is lower because of short supply, Kisch said.)

Once a person or family gets a referral, a navigator helps them gather documents, apply for specific units, sign a lease, and move in. It’s not a given that someone who’s been on the streets would have IDs, bank records, or other necessary documents.

To some extent or another, critics want reforms across all these steps: the questionnaire, scoring, and referral. But reforms will only work if a fundamental fact changes: There aren’t enough homes.

HSH’s portfolio includes more than 12,000 units of permanent supportive housing (PSH) and 2,000 rapid rehousing units. Last year, more than 19,000 people were active in the coordinated entry system. About 9 percent moved into PSH, and 3 percent received a rapid rehousing voucher, according to HSH.

The PSH vacancy rate is just over 8 percent; the city’s goal is to bring it down to seven.

Mayor Lurie made a campaign promise to add 1,500 shelter beds to the homeless system – a pledge he has since dropped — but he didn’t make specific promises about new supportive housing. A Lurie spokesperson referred questions about new housing to HSH.

The recently approved plan to rezone parts of the city is supposed to make way for tens of thousands of new homes. The original blueprint called for about a quarter of those units earmarked for very low-income residents.

But expectations for construction, market-rate or otherwise, have been tamped down. SF is highly unlikely to meet its ambitious goals. Even under the rosiest scenario, there won’t be a significant influx of new low-income housing for years without a wave of additional public spending.

With the Trump administration, the outlook for new supportive housing is getting gloomier, not rosier. In part two, we’ll dive more deeply into coordinated entry’s problems, potential fixes, and the shifting political winds blowing more strongly against city efforts.

Part 2 is coming later this week: What an audit found. An immigrant family’s limbo. ‘Not everyone is eligible for something.’

More from The Frisc…