[This is a two-part series. For part 1, click here.]

Soon after arriving in San Francisco from Honduras in 2023, Maria Zavala, her husband, and three young kids enrolled in coordinated entry, SF’s system to help people get off the streets and into housing.

That system is meant to prioritize the most vulnerable residents, but city officials and people who need housing say it’s confusing and sometimes unfair.

Like everyone who goes through the process, Zavala received a score that marked her family’s place on a housing wait list. For two years, while they waited for a home, the family lived in cars, closets, shelters, hotels, and on the streets. Zavala’s seven year old, Samara, began suffering from complex medical issues in 2024, and in August 2025 underwent several surgeries.

One of the coordinated entry nonprofits Zavala was working with was Compass Family Services. Compass told her to submit letters from the hospital describing Samara’s condition. Even with the documentation, Zavala says their score went down, not up. Compass workers blamed it on the evaluation system, says Zavala: “Even though Samara was in this really difficult and vulnerable situation, the blessed computer didn’t have feelings or a heart.”

(Editor’s note: The interview with Maria Zavala was conducted in Spanish with the help of a translator.)

A year before the family arrived, SF’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) set out to reform coordinated entry. There’s no way to know if the Zavala situation would have been solved faster if reforms had taken place. But the city still hasn’t finished. And now a larger problem for the system — and for families like theirs — is looming.

Coordinated entry relies on federal funding, and the Trump administration wants to make it harder to get those dollars — nearly $60 million was last year’s total for San Francisco, roughly 10 percent of HSH’s annual budget.

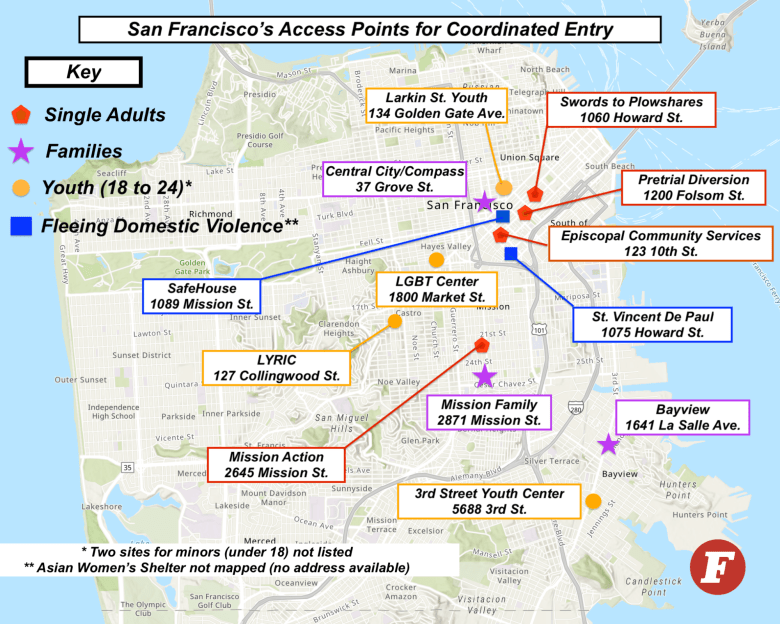

San Francisco’s access points for homeless people seeking housing and other services are concentrated in the Tenderloin and South of Market, with others in the Castro, Mission, and Bayview. (Sources: HSH, Open Data SF, The Frisc)

San Francisco’s access points for homeless people seeking housing and other services are concentrated in the Tenderloin and South of Market, with others in the Castro, Mission, and Bayview. (Sources: HSH, Open Data SF, The Frisc)

Part one of this series examined how coordinated entry is supposed to work. Part two will examine what’s gone wrong, how the city is trying to fix it, and the potential effect from federal crackdowns.

Fast, then slow

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants between $2 billion and $3 billion a year to cities and counties for homelessness services. To receive its share, San Francisco must conduct a biennial “point in time” count and operate a coordinated entry system. The city launched its version in 2018.

In early 2022, the nonprofit Coalition on Homelessness, whose leader has helped shape city policy for years, published a critical report. It said SF designed coordinated entry without input from service providers.

Around that same time, HSH launched a three-part redesign. The first step: hire an outside research firm to analyze flaws. The next step: form a working group to make recommendations. The final step would turn those recommendations into reality.

HSH got through the first two phases rather quickly. The analysis, from Focus Strategies, came out in July 2022 and highlighted several problems. Then the working group, made up of city and county staff, homelessness workers, and community members, issued recommendations in Jan. 2023.

The final phase, implementation, began in May 2023. It’s still underway. “We knew the redesign process would take time,” says HSH deputy director for communications and legislative affairs Emily Cohen. “The commitment to community input and ongoing engagement has made the process a bit longer than desired.”

A person in a sidewalk encampment sits through a recent downpour on the corner of Polk and Geary. (Photo: Alex Lash)

A person in a sidewalk encampment sits through a recent downpour on the corner of Polk and Geary. (Photo: Alex Lash)

Conditions have changed since coordinated entry’s pre-pandemic launch. COVID scrambled city services. The number of people without a home — whether sleeping on the sidewalk, in a tent, in a vehicle, or in overnight shelters — grew almost 40 percent from 2019 to 2024. COVID-era experiments, like sanctioned tent sites, “shelter in place” hotels, and secure parking lots, were mostly dismantled once the pandemic ended.

It’s not unusual for cities and counties to tweak their coordinated entry systems. But San Francisco’s reform is now more than three years in the making.

To understand why, it’s important to dive into what was in the consultants’ report back in 2022.

What the report found: mismatches

Focus’s report was clear that the pressure for reform was local. SF’s system “generally met federal requirements.”

Housing scarcity requires priorities. Then, as now, coordinated entry used a questionnaire and scoring system to sort out people’s eligibility for the housing wait list and other services.

According to Focus, this was the problem at the heart of coordinated entry. Service providers and people on the streets said the questions and scores were confusing, invasive, and unfair.

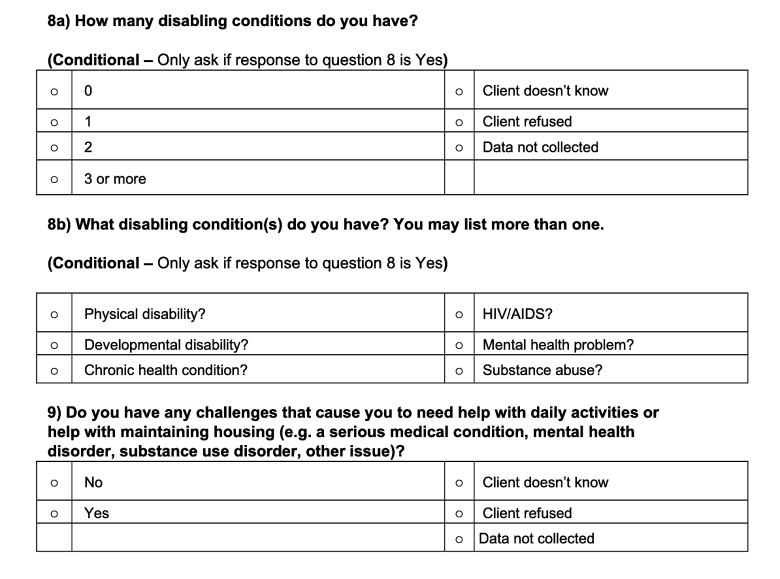

These three questions from the coordinated entry questionnaire ask participants about disabilities.

These three questions from the coordinated entry questionnaire ask participants about disabilities.

In the Focus report, HSH officials said the questionnaire does a good job determining who is most in need. But nonprofit workers who administer the questions said the process focused too much on an overall score and not enough on identifying specific resources for people.

This was also a complaint in the Coalition on Homelessness report, which Focus quoted: “Coordinated Entry should be about connecting people to the correct resource, not about giving people a score to disqualify them from help because of limited resources.”

Participants are ‘often upset’ about the wait. Single adults often don’t realize that the system only matches them with housing, not temporary shelter.

Local Homelessness Coordinating Board co-chair Megan Rohrer

Instead of matching resources with greatest need, it matches people with what’s available. With limited resources, not everyone can get housing when there’s a shortage. “One of the toughest things about the job here is telling people, ‘You don’t qualify for housing and we don’t have anything else for you,’” says Episcopal Community Services chief program officer Chris Callandrillo, whose organization also runs an access point. “Not everyone is eligible for something.”

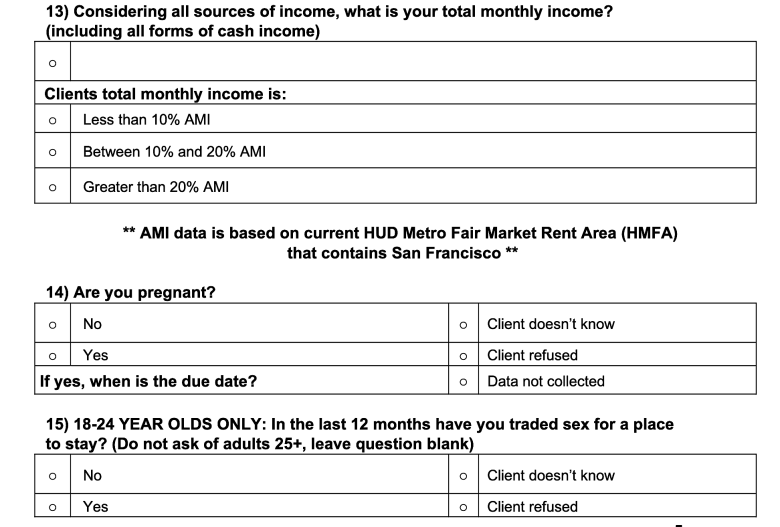

Questions 13, 14, and 15 from the coordinated entry questionnaire: What is your total monthly income? Are you pregnant? Have you traded sex for a place to stay?

Questions 13, 14, and 15 from the coordinated entry questionnaire: What is your total monthly income? Are you pregnant? Have you traded sex for a place to stay?

Critics said that even when making matches, coordinated entry is flawed. For example, some housing providers had “intense concerns” about people with mental and physical health problems coming to them who needed more help than their facility could offer.

On the family side, Zavala said the questionnaire wasn’t matching her to the proper resource. “They would never take any information about the health of my kids. They would only ask about the health of me and my husband,” she said. “The questions don’t produce a score that aligns with reality.”

What the report found: access problems

The Focus report said more than 75 percent of people didn’t know how to find help, and more than 50 percent said it took six months or more to access services. A person first has to get to one of SF’s access points before they can take the questionnaire.

The report also said some groups weren’t getting results that represented their share of the overall population. For example, in SF’s 2022 count, 30 percent of the homeless population was Latino, but Focus found only 20 percent of people filling out coordinated entry forms were Latino.

Focus also found that Black participants who got a housing referral were 30 percent more likely than Whites to get rejected by a housing provider. According to HSH, the most common reason for a housing rejection is a background check. (In the 2024 count, 29 percent of SF’s homeless population identified as White and 24 percent as Black.)

The study also found communication problems. including one that seems to violate HUD standards: making housing eligibility criteria public.

Critics say HSH should also provide more clarity about coordinated entry’s limitations. Participants are “often upset” about the wait, according to Megan Rohrer, co-chair of the Local Homelessness Coordinating Board. Single adults often don’t realize that the system only matches them with housing, not temporary shelter. (Coordinated entry only matches families with shelter.)

People also mistakenly think shelter stays will give them a leg up on housing. “They’re not statistically more likely to get federal housing because they went through a shelter. ” Rohrer said. “Coordinated entry is designed to help people who are the least likely to be able to navigate other systems of support.”

Focus authors also criticized a lack of basic standards and training across access points. This was one of Zavala’s main complaints. She said she had worked with both family access point providers, and one set of staff gave her more information on her score and eligibility than the other.

Phase 2: recommendations

With the Focus report in hand, a workgroup began meeting weekly in Sept. 2022. Four months later, it produced four sets of recommendations to improve coordinated entry. (Each set was extremely detailed. What follows is an overview.)

First, the workgroup recommended improving how coordinated entry is governed. Board members suggested two new committees: one to implement recommendations and another made up of formerly homeless people to assist.

The second recommendation called for hiring more staff, especially people who have been homeless themselves, and for standardized training and more access points.

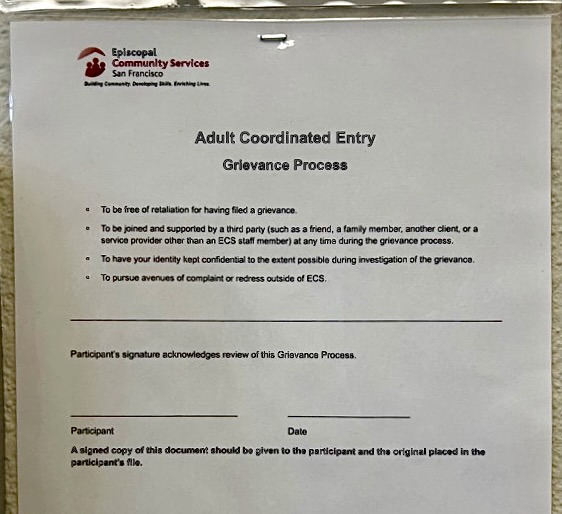

The third recommendation was about communication. The board called for creating a Client’s Bill of Rights and an oversight committee to review grievances.

One part of the form that participants in coordinated entry fill out to file a grievance. This version was posted inside ECS’s 10th St. access point. (Photo: Ayla Burnett)

One part of the form that participants in coordinated entry fill out to file a grievance. This version was posted inside ECS’s 10th St. access point. (Photo: Ayla Burnett)

The board also recommended posting written standards at access points to give visitors a clearer understanding of services they can expect. Also in this category: developing a mission statement and public meetings to disseminate information.

The final recommendation struck at the heart of coordinated entry. It said to get rid of the scoring and priority system. Everyone coming to an access point should hear a standardized description of what to expect — including automatic placement on the housing wait list. They would still take the questionnaire, but it would pose more “inclusive” questions about experience with discrimination, length of time in San Francisco, and eviction history.

Phase 3: Waiting for more studies

A few of the recommendations have become reality. There’s now a mission statement, more access points, unified training standards, and information at access points available in more languages. While there is a Client’s Bill of Rights, it’s only available in an online document that requires a password

Other recommendations have yet to materialize. HSH answers to five different oversight bodies, but there’s no grievance committee, which Rohrer said was crucial. “The original pitch was for an oversight group that would make sure every coordinated entry site was living up to [standards],” Rohrer said. HSH decided the committee wasn’t necessary.

Most concerning to critics, however, is that HSH still hasn’t changed the questionnaire and scoring system. The agency says it’s waiting for a study from an outside contractor, which HSH hired in March 2025.

Results are due in early 2026, but it’s not clear when they’ll turn into fixes. Cohen says coordinated entry changes will be rolled out via a broader evaluation of every HSH program, which began last year.

Suing HUD twice

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is trying to impose new rules for its funding.

First, HUD would prohibit funding for programs with policies that support DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion), “gender ideology,” elective abortions, or “sanctuary” immigration.

The orders are on hold. In May, SF City Attorney David Chiu and officials in other locales filed suit. “These new grant conditions blatantly violate the Constitution and endanger people’s lives,” Chiu said in a statement. “This is part of Trump’s strategy to push his ideology by threatening local programs and budgets.”

1174 Folsom was once 42 market-rate apartments. San Francisco bought it for nearly $30 million to convert into supportive housing for previously homeless young adults. With a shift of federal funds, projects like this would be more difficult. (Google Street View)

1174 Folsom was once 42 market-rate apartments. San Francisco bought it for nearly $30 million to convert into supportive housing for previously homeless young adults. With a shift of federal funds, projects like this would be more difficult. (Google Street View)

The U.S District Court for the Western District of Washington issued an order blocking HUD, so for now the new conditions can’t kick in, city attorney spokesperson Jen Kwart told The Frisc. HUD has appealed, which further stalls the coordinated entry overhaul.

“We’re using every method we can, but [it’s] harder to [make changes] in the public light in the midst of a retaliatory federal government,” says Rohrer.

Second, HUD wants to shift federal homelessness funds away from permanent supportive housing and toward temporary shelter. Each locale applying for those funds would be able to spend no more than 30 percent on permanent housing, down from the current 87 percent.

It would make sense to invest in more permanent options that actually reduce homelessness.

National Alliance to end homelessness chief equity officer Mary Kenion

Announcing the shift in November, HUD Secretary Scott Turner said it’s meant to get people off the streets faster and reduce the “never-ending government dependency” on federally subsidized housing.

California sued, calling the cuts callous and cruel. Soon after, several counties including San Francisco joined the National Alliance to End Homelessness to file another lawsuit. SF stands to lose more than 2,000 supportive housing and rapid rehousing beds — about 14 percent of its inventory — and $34 million, according to the National Alliance.

While shelter and other short-term solutions are “critical in any homeless response system,” National Alliance chief equity officer Mary Kenion says, “it would make sense to invest in more permanent options that actually reduce homelessness.”

After HUD sent confusing signals about the shift, a federal judge temporarily blocked the rule a week before Christmas.

Meanwhile, with the help of local advocates, Maria Zavala and her family found a home two months ago — with an odd twist. While on the coordinated entry wait list, she also signed up for the affordable housing lottery run by the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD). Offers from each system came through around the same time; the MOHCD apartment was a better deal.

Zavala said their Bayview apartment is a perfect fit, but she’s concerned about others dealing with coordinated entry. “There are many more families in this situation,” she said. “The system needs to be more empathetic, more transparent, and it needs to take into account people’s real needs.”

More from The Frisc…