(AP) — Graduate student workers are making an unusual request in their contract negotiations with the University of California: a legal fund to help them navigate visa issues.

The ask from United Auto Workers Local 4811, which represents 48,000 teaching assistants, postdocs and researchers at UC Berkeley and other UC campuses — including 15,000 at UC Berkeley — comes amid increasing uncertainty for international students about their future in the United States as the Trump administration ramps up restrictions on immigrants and foreign visitors.

About 40% of the union’s members come from other countries, according to its leaders.

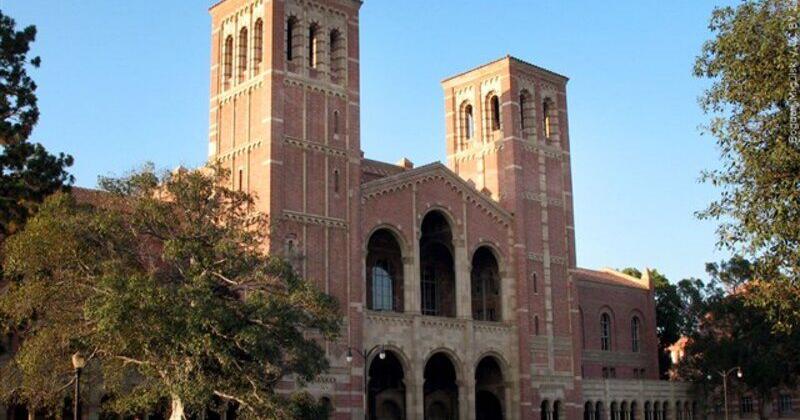

“One of the things that has allowed the University of California to be a world leader in education and research is the fact that we welcome people from all over the world,” said Tanzil Chowdhury, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. student in materials science and engineering who chairs the committee negotiating on behalf of teaching assistants and graduate student researchers.

They’ve been negotiating with the university for months over a new contract; the current one expires Jan. 31. Separate contracts for non-student researchers expire next year.

Chowdhury said union members decided to make support for international student-workers a priority after witnessing “a lot of attacks on international researchers” in 2025. In addition to the $750,000 legal fund, they’re asking the university to continue paying researchers who are temporarily stranded outside the U.S. due to visa issues, and reimburse them for visa-related fees.

“The University values the contributions of its international student employees and continues to engage in good faith with UAW to bargain a successor contract,” UC spokesperson Heather Hansen said in an email.

This spring, UC Berkeley international students panicked when the Trump administration abruptly canceled 23 visas for students and recent graduates of the university, before reinstating them weeks later. Nationwide, the administration has arrested and tried to deport pro-Palestinian international students who were legally present in the U.S., required visa applicants to make their social media profiles public so the State Department can review them for “hostility” to the country, and proposed limiting students’ visa terms to four years rather than the time it takes to earn their degrees.

“I have lived in the U.S. for about four years now, and I’ve never felt at risk until this year,” said Rahoul Banerjee Ghosh, a graduate student researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Banerjee Ghosh, who is from India, said they were thrilled to study in Berkeley, “the bastion of scientific enterprise,” where their research focuses on new materials for storing, transporting and generating energy. They’re scheduled to teach introductory chemistry to first-year UC Berkeley students this semester.

But Banerjee Ghosh said they and other international students are increasingly worried about either losing their immigration status while in the U.S. or not being able to return to the country after trips abroad. Banerjee Ghosh has missed opportunities to travel to conferences in Europe with their colleagues, and fears that if they try to renew their visa when it expires later this year, it could be delayed or rejected, leaving them stuck outside the U.S. without their passport.

“Appointments are canceled and rules are changing every day,” Banerjee Ghosh said. “It’s an ever-present thought: Will I be able to continue my degree, continue the life I’ve built here?”

Funding challenges on horizon for Berkeley International Office

International student workers can get referrals to legal services from their campus’s international student office, Hansen said.

But the Berkeley International Office faces its own budget challenges: Former Chancellor Carol Christ allocated about $700,000 per year in student service fees to the office — which provides visa assistance and advising — over a five-year period, but that money is set to expire after this school year. Meanwhile, the office’s advisors have been working harder as they race to keep up with changes in federal policy, said Rayne Xue, a student government senator who advocates for international students.

“The advisors are definitely spending more time tracking federal legislation and policy updates,” Xue said. “They’re supporting and helping out with more students that are more frustrated than ever before.”

The demand for support for international employees is unusual in higher education labor negotiations, but not unprecedented. Johns Hopkins University signed a contract with its teaching assistants in 2024 that gives international employees up to two weeks’ paid time off if they need to leave the country to renew their visas. The university also set up an international employee fund to which workers can apply for help covering visa fees.

The Institute for International Education reported a 17% decline in new international students enrolling at U.S. colleges between 2024 and 2025. Official fall enrollment numbers for UC Berkeley, which in the past has enrolled more international students than any other UC campus, have yet to be released. But the Daily Cal reported that the number of international students submitting paperwork saying they intended to register grew this year, an early sign that UC Berkeley could buck the nationwide trend.

The University of California also spends about $3 million per year on legal services for immigrant students through its Immigrant Legal Services Center. A separate UC Berkeley program in partnership with the East Bay Community Law Center serves primarily students who don’t have permission to be in the country.

Union members and the university have already tentatively agreed that administrators won’t disclose an employee’s immigration status without their permission unless they’ve received a warrant or subpoena, and that the university will notify the union if federal immigration agents are on campus.

This story was originally published by Berkeleyside and distributed through a partnership with The Associated Press.