Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

Lynne Gerber is “too Jewish” to join a church, she says. But when she moved to the Bay Area in 2001 to do doctoral work in religion, she went to a school where a lot of students were studying to become ministers for the LGBTQ-affirming Metropolitan Community Church. They invited her to worship—she went and became a “friend” of the church.

A few years later, Gerber, who is now an independent scholar in San Francisco, found herself studying how churches deal with trauma and examining how MCC San Francisco handled the AIDS crisis. In the process of that research, a longtime congregant introduced her to a collection of audio recordings documenting the services and activities of the church during that time period.

It’s these 1,200 tapes that have formed the basis of When We All Get to Heaven, a 10-part narrative podcast developed over 10 years by Gerber with her production company, Eureka Street Productions, and distributed by Slate. The series features beautiful archival sound, of the choir, of course, and of the voices of MCC leaders and congregants discussing the fraught and yet necessary place of spirituality in queer life during a time of crisis. There is sadness, but there is also joy.

On a recent episode, Bryan Lowder and Christina Cauterucci, hosts of Slate’s Outward podcast, spoke to Gerber about making this project and what lessons can be applied to the current moment. This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Christina Cauterucci: For listeners who aren’t familiar, what is the Metropolitan Community Church?

Lynne Gerber: It’s a gay-positive church, founded in 1968 by the Rev. Troy Perry. Perry grew up a Pentecostal Baptist in Florida. Perry was a minister in a Pentecostal denomination and was struggling with his homosexuality. He was outed as gay in two different churches that he pastored, and both times the church said: “This is unacceptable. You’re going to have to change, or you’re going to have to move on.” The first time, he tried to “change,” and the second time he moved on to Los Angeles. He decided that being gay was a good thing, that the problem wasn’t with being gay but with how people were understanding God.

It took him a couple of years, trying to figure stuff out. But he heard God telling him that there needed to be a space for gay people where it was recognized that God loved them, that God made them, and God knew full well how God made them, and that that was fine with God.

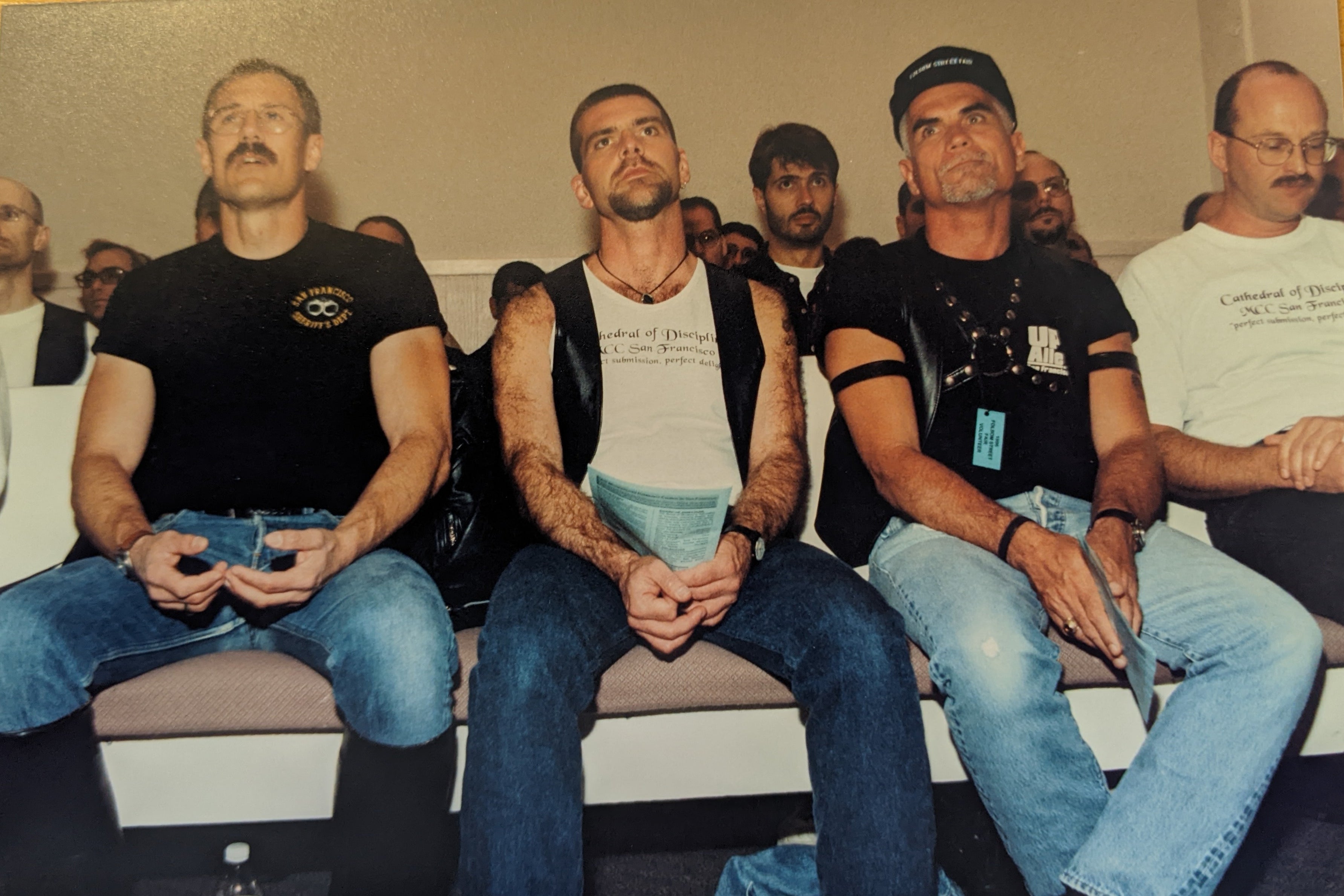

Metropolitan Community Church

Perry felt as if he needed to make a space where that could be true, and he did that in his living room in Los Angeles, which then became a church and a congregation, and then became multiple churches. It was an organization that had people meeting every week in places around the country that a lot of the larger gay organizations couldn’t reach.

Bryan Lowder: The story of your research and how we get to what we’re listening to now really starts there, when this congregation rescues these amazing cassette tapes and gives them to you. Can you tell us a little bit about how that happened and then how you started listening to them?

Gerber: So these tapes started to get made by a guy named Keith Wismer, who began the recording program at MCC San Francisco. He passed away in the mid-’90s.

This guy, Steve, took over the sound room for a while, and he introduced me to these tapes. In the early aughts, the church was relocating, so they were cleaning house. They had put these boxes and boxes of tapes on a shelf for the garbage, and Steve said, “That’s not happening.”

He found a space underneath the floor in the sound room. He shoved them under there and put all these cables and junk on the other side so nobody would poke in there to pull them out. And then I’m sitting in the church office one day, following up on the research that I was doing, and he was like, “Do you know about these tapes under the floor of the center?”

It was a collection of 1,200 cassettes that are recordings of two worship services pretty much every Sunday between 1987 and 2003. I was teaching at UC–Berkeley at the time. I had a team of research assistants with me, and we just started listening. We digitized a collection of 325 of them, which is what the series is ultimately based on.

Cauterucci: How did you decide which ones to start listening to?

Gerber: We did two samples. For the first, we created a grid of how to get a semi-representative sample from all the years. For the second, we picked whatever the hell we thought was cool. The only thing we could tell is what was written on the box.

Metropolitan Community Church

Lowder: Just so our listeners can get a sense of what you heard, can you describe one piece of tape, maybe something that really surprised you or moved you? Something that you weren’t expecting and that made it into the show?

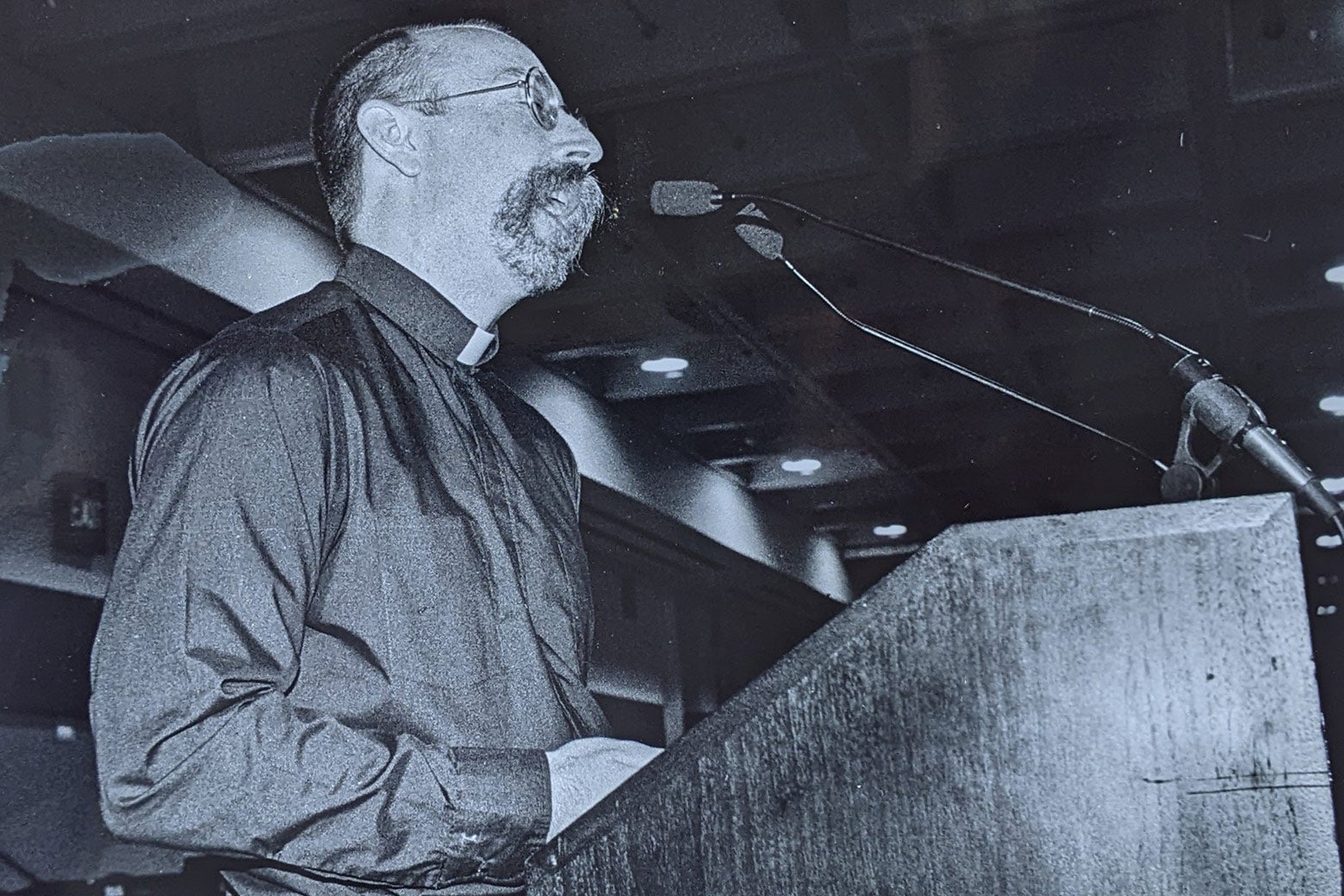

Gerber: The opening tape is a tape of Jim Mitulski talking about what it’s like to almost forget people that you’ve lost and what it means to not be able to remember their name. It was so striking because it reflects the magnitude of the loss that these folks were living through—that it’s person after person, after person, after person.

I think that tape is from 1993. It’s 12 years into the crisis. It’s a little horrifying to think, but it happens—we forget. And he said it: This was a church where you could name that that had happened and it didn’t make you not an adequate lover of your beloved people or an inadequate friend.

It was like, No, we are human people, and part of the reason we gather is to remember, because the tide is so big and it’s so fierce, and it’s wiping away so many people that we’re just gonna hold on where we can. His courage to name such a complicated feeling in a worship service in church, which seems to be a bit more of an emotionally buttoned-up kind of place, was really striking.

Cauterucci: There’s been a lot of cultural material made about the AIDS crisis: films, books, other podcasts. What do you think this lens of spirituality, and specifically this congregation, helps us understand about the AIDS crisis that these other representations don’t get at?

Metropolitan Community Church

Gerber: Religion, and spirituality, is an interesting place to explore how people deliberately cultivate hope or sustain themselves, or they cultivate joy in a way that is related to all of their political activism and medical activism and care work.

But it is also a space completely independent of that, that is really of imagination structured by a worship service. It’s structured by music and pieces of the Christian tradition. In this case, it’s also structured by pieces of the queer tradition. Queer literature is evoked all the time, and queer music is sung all the time, and it’s a place to watch people work to cultivate hope and possibility.

The sheer insistence on possibility and the commitment to gather and to cultivate a sense of hope through years where they had no idea how this would turn out—they had no idea that the dying would ever end—gave the energy to do all of the rest of the other things that all of those other shows and podcasts are about. And that to me is tremendously moving.

For this time, when we are in a moment when we have no idea how this is going to go and where it’s going to end up and how we get there, the practices of what it takes to hang in through that, in a community with a sense of imaginative possibility that insists on everybody’s place in it and that directly counters the messages that are the loudest in the culture, speak powerfully to what’s happening now.

Lowder: You’ve been working on this for a decade, and we understand that scholarly work is not a fast process, so that’s part of it. But what is it about this, about San Francisco and about this story, that kept you invested for so long?

Gerber: It’s been a decade since I started working with my two co-creators: Siri Colom and Ariana Nedelman. I was introduced to this archive in 2011, and I was at an interesting crossroads because I had been working in a world that did not speak to my own religious sensibilities. You can dry out. You can become hard. You can become cold to your topic.

I did not want to become cold to my topic. And I was asking myself, Was there a place that felt like—the religious metaphor is “living waters”—waters that are actually nourished? And MCC San Francisco had always been that to me, not officially, just as a human person, even though I was never really a member.

Listen now to the first two episodes of When We All Get to Heaven.

Cauterucci: These past 10 years have spanned some pretty tumultuous times in American life too, for queer people and for many other communities. In this moment, what does this work mean to you, and what do you hope listeners take away from it?

Gerber: I hope people hear that there are communities of queer people who have been through really hard things before, and this is how they got through them, and these are some possibilities. I hope that people take very seriously the work of cultivating hope and imaginative possibility and of celebration and of ritual.

Everyone Thought It Was the Ultimate Answer for a Great Burger. Everyone Was Very Wrong.

Staying Single by Choice Comes at a Cost. These Women Have Done the Math.

Slate Mini Crossword for Oct. 18, 2025

I Needed to Stop Snoring. I Tried Everything I Could Find. The Solution Was There All Along.

To me, the act of cultivating imagination and possibility, of telling better stories and trying to live into them, even if it’s just for an hour a week, is an essential part of what social movements are about. That can look like a lot of different things. But it needs to be there. It’s not all agendas and campaigns and goals and marches and logistics. It is all those things, but it’s not only those things. And to make the space to imagine and to cultivate possibility on our own terms, I think that is incredibly important, and it’s something that’s undervalued.

If we’re going to get through this, we have to hold on to each other. Again, it’s not replicating MCC—it’s insisting on making a space that MCC insisted on making.

That could look a lot of different ways. But I really hope that people think very, very seriously about, and really value, the imaginative work of an alternative space, another world again. Even if it’s just a temporary version of it, that muscle needs to be moved, and it helps to get together and sing ridiculous songs and even great songs and even moving songs. It helps to be together and to sing together and to express the possibility of love in something different together. It just helps. It really helps.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.