The pandemic was a crisis unlike any other for San Francisco’s century-old public transit system. Muni’s core ridership of downtown workers still hasn’t returned in full force, and a roughly $300 million budget hole looms this summer.

Over many months, officials have pieced together a funding rescue plan, but it still requires many things to go right.

One of those requirements was hinted at Friday morning but without specifics some expected. California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office unveiled its 2026-27 state budget proposal, which described a loan for local transit agencies as a “significant budget adjustment.” It said nothing about how much money could come to the region.

The Bay Area’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission has been negotiating for months on behalf of Muni and other agencies. MTC director of legislation and public affairs Rebecca Long told The Frisc last week that the most recent figure is $590 million, less than what officials had originally sought. It’s also unclear how the money would be divided among local agencies.

The lack of clarity around the loan continues months-long frustration. Local advocates thought last summer that a $750 million loan was forthcoming. But Newsom backed off, and negotiations have continued. MTC’s Long said today in a follow-up email that a meeting with state finance officials is scheduled for tomorrow to discuss terms.

The loan is necessary because the rescue plan leans on two ballot measures, likely to be put forth in November. One would raise Bay Area sales taxes, the other would add a new San Francisco parcel tax, which is a type of property tax. If voters say yes, which is no guarantee in a volatile political climate, the sales tax revenue wouldn’t start flowing until summer 2027, and the parcel tax in 2028.

The loan would help fill that gap. But Muni would still likely have to make budget cuts.

It’s been doing so — or simply not restoring pre-pandemic levels of service — in the past couple years. For example, it has never brought back the 3 Jackson or the 2 Clement. In early 2025, the agency also shortened or combined several downtown routes, reduced the frequency of mid-day runs on three neighborhood routes, laid off 30 managers, and cut more than 500 full-time positions that had been unfilled but budgeted for in past years.

SFMTA shortened some routes, like the 5 Fulton, to help cut costs. (Photo: Lisa Plachy)

SFMTA shortened some routes, like the 5 Fulton, to help cut costs. (Photo: Lisa Plachy)

But Muni officials must also plan for the possibility of one or both measures failing this fall. Some ideas for drastic cuts, which came to light in the Muni Working Group meetings in 2025, included stopping all regular service at 9 p.m., cutting frequency of buses and trains 50 percent, or cutting street car and cable car service.

Selling the parcel tax

The terms of the state loan still seem to be in flux, but SF officials at least have resolved one question after months of negotiation: What kind of parcel tax hike they’ll ask local voters to approve.

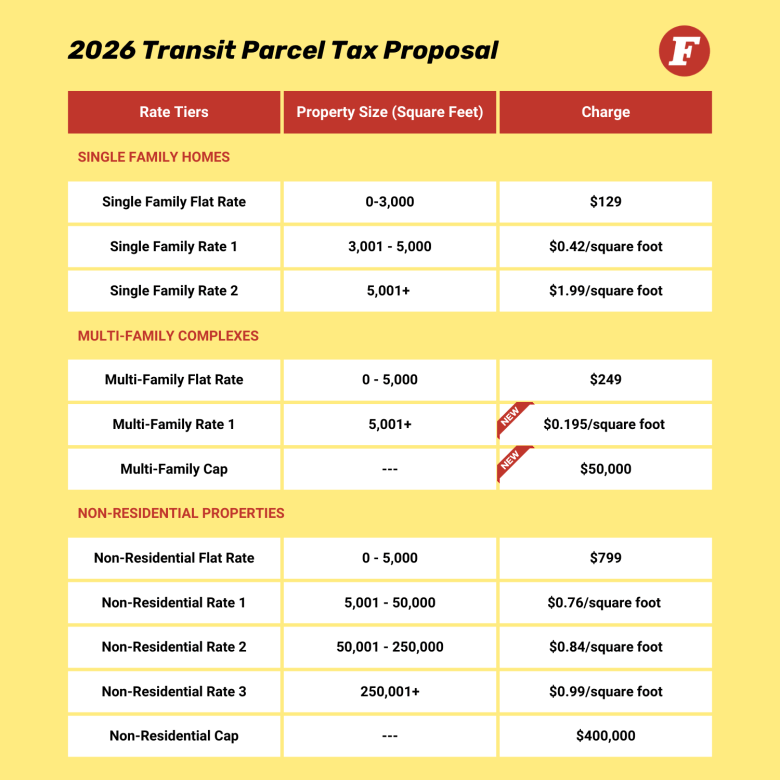

Last week, SFMTA issued a final draft of the proposed parcel tax. Single family homeowners would pay $129 annually for properties less than 3,000 square feet, while multi-unit building owners would pay between $249-$50,000 each year depending on the square footage of their buildings. Commercial property owners would pay between $799 and $400,000.

SFMTA says the latest plan would bring in $183 million in its first year. That plus the sales tax, which is expected to generate $160 million a year, would cover Muni’s projected deficit for the coming budget year, but would fall short in succeeding years.

A previous version of the local tax didn’t win the backing of the San Francisco Transit Riders group and other members of Muni Forever, who said it was too onerous for renters because landlords could pass through some costs to tenants.

The latest version, which SFMTA said all parties agreed to, caps what landlords can pass through to rent-controlled tenants at $65 per year. There are also exemptions for residents of single-room occupancy buildings and for seniors, as well as lower rates for multi-family units.

These changes are meant to ensure that residents of rent-controlled units pay less than owners of single-family homes, SFMTA executive director Julie Kirschbaum said last week.

Cut no matter what?

Even if the measures pass, SFMTA says it will continue to cut costs and find “efficiencies.”

Kirschbaum, who ran SFMTA’s transit division for years under former director Jeffrey Tumlin before taking his place in 2025, already ordered all divisions to cut budgets 5 to 7 percent for the fiscal year starting in July.

These cuts could include things like changing maintenance schedules to reduce evening work hours when premium pay is in effect. SFMTA also wants to squeeze costs from future supply contracts and save money by replacing or retiring old equipment, such as seldom-used ticketing machines.

Muni service efficiencies could also reap benefits. SFMTA studied 11 other agencies, including Seattle, Miami, Los Angeles, and Oakland, for a service comparison. SFMTA found that it has the slowest moving buses, in part due to operating in a dense, urban area with narrow streets. It also has one of the highest operating costs.

Increasing Muni speed could cut costs, noted Livable Cities senior policy manager Tom Radulovich. He cited a 2006 story about a Muni study showing that a 2 mph increase in speed would allow the system to carry 12 more passengers per hour and cut operating costs by 20 percent. “There are huge efficiency gains to be made if you speed up Muni,” he said.

Last week, Kirschbaum acknowledged that ways to speed up service, such as building more bus only lanes, and creating more “rapid” routes, would be welcome, but “resources are a constraint.”

All these ideas hinge on three things falling into place: the state loan coming through and voters approving both ballot measures. Otherwise, SFMTA will have to make drastic cuts, even to entire Muni lines. It’s a doomsday scenario they’re hoping voters and state legislators want to avoid.

More from The Frisc…