As 2025 ended, San Francisco housing boosters had little time to savor the December approval of the city’s historic upzoning plan, which allows for taller, denser neighborhoods on the city’s west and north sides.

Around the same time, news broke about plans to build a 25-story apartment building on the site of the Marina Safeway. Even the zoning plan’s backers objected. Now the project promises to turn up political pressure going into a critical election year when housing will be a hot-button issue in several races.

Now another waterfront tower is in the works. It’s in a different part of town, where high rise apartments have sprouted for years, but it’s also in the very spot where angry neighbors once turned a proposed development into an ugly fight.

That development wasn’t hundreds of apartments, like the current proposal, but a specialized homeless shelter. That shelter, officially the Embarcadero SAFE Navigation Center, not only survived that fight but has become a neighborhood fixture. And now, if the new tower — or towers, actually — become reality, the shelter will have to go.

The shelter, comprised of 200 beds in three large quonset huts on a triangular sliver of land, has always had semi-temporary status. Since its initial 2019 approval, the lease has been renewed — uncontroversially — every two years. Given the economic slump, it could still remain for years.

“My understanding is they were only going to stay there as long as they would not be hindering the development,” says Rick Dickerson, one of the original members of the Embarcadero advisory committee formed to track conditions and advocate for the neighborhood.

The Embarcadero SAFE Navigation Center is comprised of three low-slung quonset huts on a triangular slice of land with apartment buildings rising above it. (Photo: Alex Lash)

The Embarcadero SAFE Navigation Center is comprised of three low-slung quonset huts on a triangular slice of land with apartment buildings rising above it. (Photo: Alex Lash)

Jesse Blout, founding partner of the developer Strada Investment Group, told The Frisc, “Even though penciling out new development is challenging, we are very bullish about the project and the prospects for starting construction in the near term.”

Still, the potential upheaval comes at a time when the city seems as uncertain as ever about how to keep people off the streets. Supervisors and the mayor have tussled over spreading shelters and services across the city — a fight that harkens back to the Embarcadero Navigation Center proposal — while Mayor Lurie’s campaign promises and the city’s ongoing programs have not all gone as planned.

But Strada and city planners say the project is an encouraging sign for more housing downtown generally, including a significant portion made affordable.

Transbay revival

The sliver of land that got so much attention in 2019 is technically “Seawall Lot 330.” It’s not right on the water; it’s across the six-lane Embarcadero from Pier 30. Strada will report to the Planning Commission tomorrow on the project: two buildings rising to 100 feet and 230 feet.

The plan calls for 619 apartments, 93 of them subsidized to be affordable. The majority will be one-bedroom units. Strada will also donate part of the same lot to the city for future development of about 100 affordable homes.

Another architect’s rendering of the Seawall Lot 330 buildings. The plan calls for 619 apartments, 93 of them affordable, plus space for a 100% affordable housing tower if the city wants to build it.

Another architect’s rendering of the Seawall Lot 330 buildings. The plan calls for 619 apartments, 93 of them affordable, plus space for a 100% affordable housing tower if the city wants to build it.

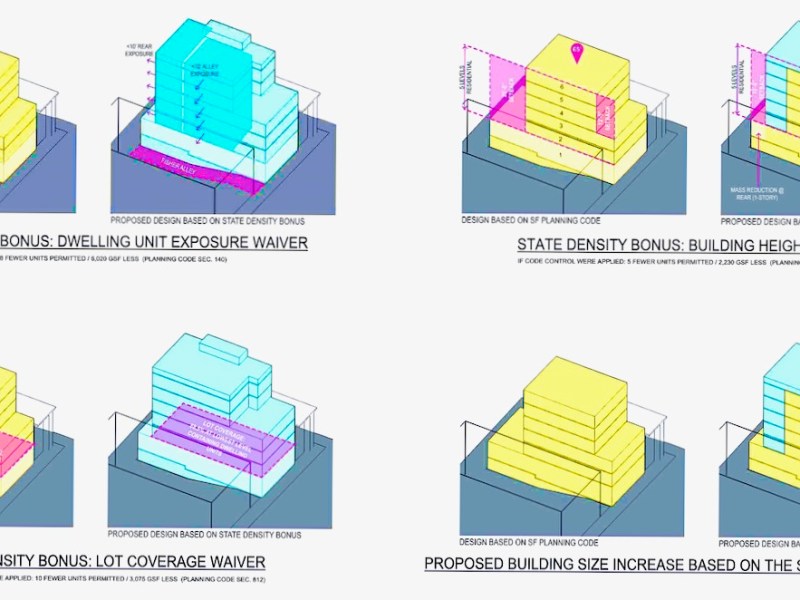

The site lies within the city’s Transbay Residential District, designed to encourage large, dense buildings in and around the Salesforce Transit Center, which is less than a mile away. The site is zoned for up to 105 feet. To build the 230-foot tower — more than 20 stories high — Strada is using a state ‘density bonus’ law that allows for more height in exchange for more affordable housing.

Strada’s Blout (who was Mayor Gavin Newsom’s deputy chief of staff) told the Port Commission last July that they could employ the same state law to build even higher but opted not to as part of negotiations with neighbors.

The two new buildings will flank the high-priced Watermark high rise, where some units sold for more than $1.8 million last year. The Watermark Homeowners Association did not respond to requests for comment.

It remains to be seen — perhaps as soon as tomorrow’s hearing — if neighbors will protest. But thanks to a 2023 state law, SB 423, protests are unlikely to have an effect.

The brainchild of state Sen. Scott Wiener, who represents SF, SB 423 cuts a lot of red tape, including letting projects bypass a Planning Commission vote.

Strada must instead inform the commission about its plans and ensure they’re complying with state rules. Then the city must take no more than 180 days to review the project (or 90 days for developments of fewer than 150 homes), a stark contrast to the years-long process many buildings faced in the past.

SF Planning estimates that in two years under SB 423, 45 developments have qualified for the same “not subject to hearing” status. These projects have included 1,178 affordable homes, although many have yet to break ground. The city lists 11 more in the “preliminary filing” stage under SB 423.

Unlike many neighborhoods upzoned by the new plan, this one has plenty of height already. But the area’s towers represent something of a bygone era, the days before COVID, when Mayor Ed Lee had ambitions to extend the downtown skyline with highrises that appealed to the tech set, offices and homes alike.

With downtown offices still roughly half-empty, the city is keen to frame this as a step forward for downtown revitalization, even if it’s stretching the boundaries. “While people might differ on where downtown begins and ends,” says SF Planning chief of staff Dan Sider, the Seawall project is “more than a good omen.”

“One project moving forward doesn’t necessarily mean anything for another project,” says the city’s chief economist Ted Egan. “But it’s all one housing market, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that we are starting to hear early news like this after a year or so of good news on the rent and price front.”

The doldrums have been severe. The project’s 619 units represent nearly 40 percent of new residential construction finished in 2024 and nearly 25 percent of 2025’s total.

Original plans, dating back to 2020, called for an office building as well. With so little demand on that side and other factors, the Port is letting Strada split the project in half and just build the residential towers.

Shouted down

Once upon a time, this location at Beale and Bryant was one of the most controversial vacant lots in San Francisco. When the city proposed it to host its latest homeless Navigation Center in 2019, it touched off a firestorm of opposition.

A big part of the push for this particular location came from then-D6 Supervisor Matt Haney, who argued that the city needed to spread services for unhoused people across a wider area, rather than concentrate them all in a few neighborhoods like SoMa and the Tenderloin. But not everyone wanted to share the load.

So many lawsuits, so much wasted money and energy.

steve good, president and ceo of five keys, nonprofit operator of the embarcadero safe navigation center

In April 2019, San Francisco’s civic politics, not to mention polity, hit an ugly low. Mayor London Breed had shown up to a community meeting about the proposed Embarcadero Navigation Center but had to cut her talk short. Attendees shouted her down and told her to “go home.” (Breed was born and raised in San Francisco.)

Pro- and anti-center sides had raised legal and campaign funds. The pro-center side got big checks from tech moguls Marc Benioff, who had recently helped convince voters to approve a business tax to fund homelessness services, and Jack Dorsey.

After the center’s approval, South Beach residents tried to block construction, calling it a “magnet” for “open drug and alcohol use, crime, daily emergency calls, public urination and defecation, and other nuisances,” and even appealing on the grounds of environmental law. Courts threw out those lawsuits and the center opened in late 2019.

The uproar spurred a Frisc investigation that found no correlation between SF’s Navigation Centers and rising crime rates.

“So many lawsuits, so much wasted money and energy,” says Steve Good, president and CEO of Five Keys, the nonprofit operator of the center.

Since then, Good says neighborhood opposition has essentially vanished, citing only a few token objections when the Port renewed the center’s lease last year. The Embarcadero Community Advisory Committee said last fall that “reports of concern have turned into thank you notes and compliments from neighbors that are noticing the cleanliness of the area.”

Good acknowledges the center must close when Strada prepares for construction but knows it could be years.

The city’s homelessness department will be in charge of hopefully finding a new site for the center. An agency spokesperson did not respond to questions about future locations but did say that the center’s lease expires at the end of 2027. The city could close the center if Strada is ready before then to build. “The site has always been intended as a temporary location,” the spokesperson added.

More from The Frisc…