Sacramento-based artist

Joha Harrison rarely tells anyone this, but there’s a

topographical inspiration behind his abstract work. “In my mind,

a lot of times I’m making a bird’s-eye view of an island,” he

says, adding that the Louisiana Gulf Coast where he grew up

“looks like an island. It has land, but also holes in the land

where water is, as if inside an island or a little

peninsula.”

“When I was younger, I used to

draw the map of the state of Louisiana over and over in class,”

he says. “I got so good at it that I could draw it and know all

the ins and outs.”

Harrison uses several mediums to

translate his memories and experience into art. After drawing and

painting throughout his youth, he started his career as a

photographer with a stack of disposable cameras, documenting the

places, people and things he feared losing. As he grew into his

practice, he professionalized his passion for photography and

ventured into filmmaking. He also continues to paint and has

works in private collections across the Sacramento region.

In this Q&A, the

multi-hyphenate artist traces how photography taught him to use

light, how the pandemic shutdowns accelerated his career as a

painter and why the heart of the artist sits in conflict with the

reality of needing to pay the bills. He also reflects on making

work that is explicitly about Black identity alongside work that

is more topographical and abstract.

What’s your artist origin

story?

I’m originally from Baton Rouge,

Louisiana. I moved to California in 2009.

My artist origin story starts in

elementary school. I remember doing more artwork than schoolwork.

Maybe that’s just the part I remember most, but I started in

elementary school. We had schoolwide competitions, and I won

several. After elementary school, I spent a lot of time doing

sports. While I was focused on sports, I wasn’t really thinking

about art.

Joha Harrison’s abstract work is often inspired by topography.

I picked

up photography in high school because my family was moving to

Georgia from Louisiana, and I didn’t want to go. I argued with my

parents at every step. I said, “I’m not leaving. I’m going to

stay with my auntie. I’m going to stay with my football coach.

I’m going to stay with anybody other than leave Louisiana.” But I

went, and I consider it one of the best decisions of my

life.

I started getting disposable

cameras from local grocery stores because I wanted to take photos

of everything I was about to leave — my life and everything. I

had about 20 disposable cameras, and for three months I took

photos of my friends and all the things I wanted to remember.

That’s how I got started in photography.

After I graduated high school, I

went to college and did photography for a church organization.

That’s when I got my first camera. I went to Best Buy, bought it,

and from there I started taking pictures of everything. Painting

came later.

How did the shutdown affect your

art?

Before that, I was mainly doing

photography and film work. I painted, too, but it was more of a

hobby. I made small pieces here and there. I started painting

full time in 2019, around the time of the pandemic. When the

world shut down, I said, “If everybody’s going to be stuck in a

house, they want pretty things on their wall to look at.” That’s

when I pivoted to doing art full time.

What does your film practice look

like?

My film practice is a mix between

documentary and experimentation. I like to tell stories that are

interesting and maybe uncommon, and treat the images that you see

like a painting that allows for experimentation within the frame.

On the other side of film, I enjoy making montage videos that are

abstract in form, made up of found videos and images similar to

my abstract collages.

You play a lot with light in your

images. How does that influence your work?

I’m at a point where I want to do

my own photo shoots and create my own images to incorporate into

my work. That takes longer than waking up and starting a

painting.

I could use my own photographs,

and I have used many of them before. Now I want to start creating

new images. It’s fun finding images on the internet that speak to

me, and they can come through in the work. But creating my own

images has a bigger impact. Everything you see comes from

me.

In photography, light is the main

thing. Without light, there is no image. How I manipulate light

is how I approach a photograph. Sometimes, at night, I’ll

manipulate the light so the scene is dark and all you see are the

lights. It depends on what I want to show. Some images need light

to say what I’m trying to say, and some don’t need as much.

However dim or dark it is, it creates a different mood and

conveys a different message.

With painting, light doesn’t play

as much of a role. It should, but it isn’t as active a factor as

it is in photography. It’s not something I think about unless I’m

trying to. In abstract work, placing light areas next to dark

areas so they interact is part of it.

A photograph from Joha Harrison’s “Between Blinks” series.

Light in photography is

instrumental and direct. Light in painting is instrumental, but

less direct.

With your more abstract works,

what are you trying to say when it’s not so obvious?

I’m drawn to abstract work

because I can make something that means 10,000 different things

to 10,000 different people. I’m not necessarily trying to deliver

one message. I’m creating in a way that can reach a lot of

people.

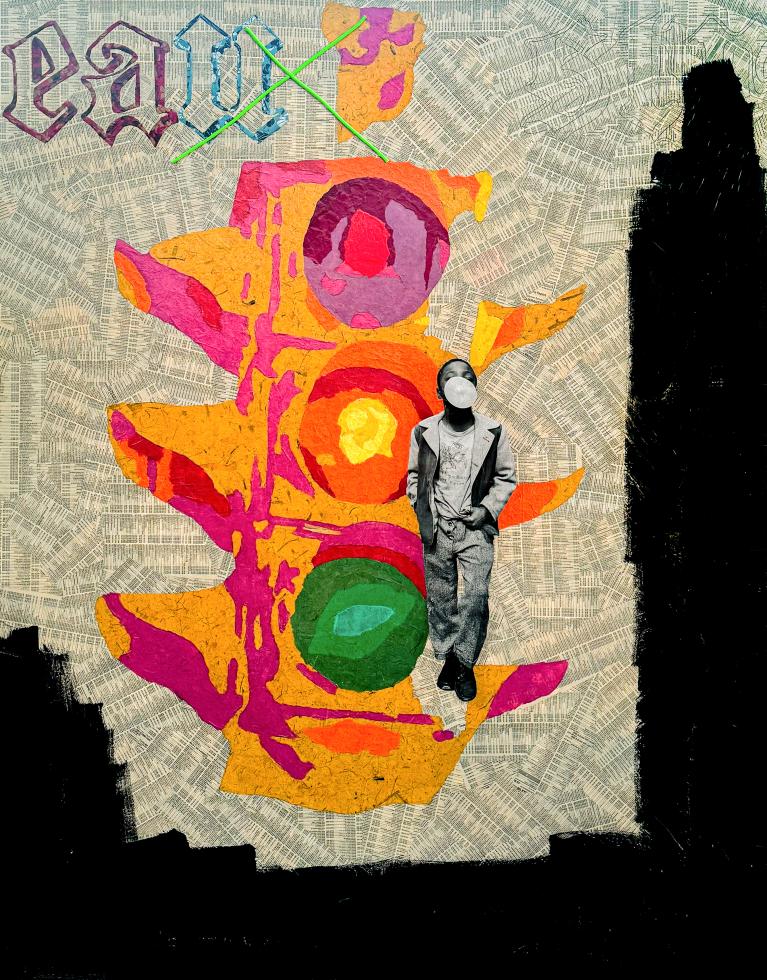

“Black Light” by Joha Harrison.

If I

made a portrait of a famous person, people who haven’t seen that

person or don’t know who they are might not feel much impact.

With abstract work, there are fewer boundaries. In pure

abstraction, the work can’t declare, “This is a Black person,

this is a white person, this is a rich person, this is a poor

person.” Anyone, from any background, can look at it. It’s almost

like something you’d see in nature — something that’s simply

there.

I’m trying to get what’s inside

of me out. I do make Black art, too, and I want to speak directly

to that. Growing up in the South and experiencing racism at very

young ages shapes my work. My parents and grandparents grew up in

that era. I grew up in an era where it’s more like residue

racism, you can’t really see it as much as you used to, and it’s

not as bold as it used to be. But those experiences shape my work

and the things I want to tell, and the direction that I want to

say something. It influences it on that aspect.

I also make abstract art, and

that can speak to that and to everyone. … A lot of the work is

subconsciously topographical. I like land masses and land forms,

and also what it looks like on the map. Specifically, the

deterioration and the erosion of the land from the water. It

makes the landscape look less than perfect, and I like work that

looks less than perfect.

If I feel like making something

highly political or something centered on Black identity, that’s

what I make. If I feel like making something purely abstract,

that’s what I make.

Sometimes I mix them

together.

You recently were in New York —

were you working there, and what was that experience like?

I was doing corporate

photography. Around the same time, I was in Illinois for a

residency about two weeks earlier.

I started looking up

things to do in New York because I had never been there. I

planned to do the work, visit a few galleries and fly home. Then

I saw that Kennedy Yanko had an opening while I was in town. I

also saw the Armory Show, which I had only heard about briefly

before that.

My flight was scheduled to leave

that day, and I didn’t think I would have time. But I went to a

gallery through a connection with local Sacramento artist

Unity Lewis while I was networking in New York, and the

staff gave me a VIP pass to the Armory Show. So I went.

It felt rushed. I didn’t realize

it would take about an hour to get to John F. Kennedy Airport. I

think The Armory Show opened at 9 or 10 a.m., and my flight was

at 3 p.m.

I met an artist named Clarence

Heyward who was showing with Richard Beavers Gallery. We talked,

and I looked at his work. He told me about another fair, Works on

Paper, and suggested that I check it out.

It was in a building by the

river, near the Lower East Side. He told me to talk to Tanya

Weddemire, a gallery owner from Brooklyn. I did, and I told her

about my struggles in the art world and trying to figure out how

to navigate it. She said I needed to understand what I wanted to

do and make a decision.

I told her that I make abstract

art and I make political/Black art. What I took from what she

said was that I should make the work that comes from my

heart.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital

Region: Follow @comstocksmag on

Instagram!