Well, here’s a shocker: Muni, the fiscally strapped transit service that slowly moves people and Takis wrappers around San Francisco, is insanely clean.

We’re not talking about the insides of Muni vehicles. You still need to look hard before you sit down. Rather, we’re talking about the tailpipes. Muni’s contribution to the city’s total emissions, as a percentage, reminds us a bit of the Crazy Eddie commercials that Dad and Uncle Steve used to flip through the channels to find in a pre-cable, pre-internet New York City: They’re so low, low, low that they’re — insaaaaaaane.

How low? We’ll get to that shortly, and in great detail. But the thing is: It’s not low enough to satisfy the state of California.

In 2019, the state mandated public transit agencies start transitioning from diesel buses to zero-emission buses. By January 2026, half of all new bus purchases must be zero-emission. By 2029, all new purchases must be zero-emission. And by 2040, the entire fleet should be zero-emission.

Muni’s emissions are low, low, low. But they’re not nonexistent. Ergo, they are not zero-emission. How much will it cost to get to zero? A lot more than zero.

Bhavin Khatri, the Municipal Transportation Agency’s zero emissions program manager, tells Mission Local that bringing Muni into compliance would run “in the hundreds of millions of dollars.” Muni is facing a $300 million deficit starting in July 2026 and is considering draconian financial measures that could eviscerate a service that has rarely worked better in recent memory.

Muni does not have the money to invest in long-term zero-emission fleet upgrades and infrastructure renovations. It doesn’t even have the money to buy the Takis chips scattered through its buses and trains.

Barring unforeseen lunacy, Khatri says that Muni will apply for an exemption and continue to run the bulk of its service via diesel hybrid buses: The cleanest bus is a full bus, and Muni needs to focus its money on that. This is an absolute no-brainer and, in a sane world, Muni will get what it’s asking for here.

Khatri believes the SFMTA will be among the first if not the first California transit agency to apply for such an exemption. But somebody has to be first: “A lot of them are probably waiting for us,” he explains.

If and when Muni takes the plunge, here’s hoping that its request for an exemption will be granted — because the standards it is being required to meet are insaaaaaaane.

In the past, Muni has been more than a little cavalier about environmental regulations. We’ve reported on this. In 1996 and again in 2013, Muni was caught needlessly idling its diesel buses for hours early in the mornings at bus yards. In 2017, we caught Muni needlessly idling its brand new $750,000 diesel-electric hybrid buses.

Even low-end new cars now automatically cut the engines to prevent excessive idling, but these expensive buses did not — because Muni inexplicably had that program disabled. After first claiming it would cost $1,200 per bus to install this program, the SFMTA, facing blowback, got it done for free.

So there’s a history here and it’s not a uniformly glorious one, especially if you live next to a bus yard. But forcing a transit agency into prohibitively expensive upgrades when it’s struggling to fund basic service is bad governance — especially when you factor in how minuscule Muni’s emissions are compared to the city writ large. How minuscule? Well, how about we put on everyone’s favorite Steve Martin album: Let’s Get Small.

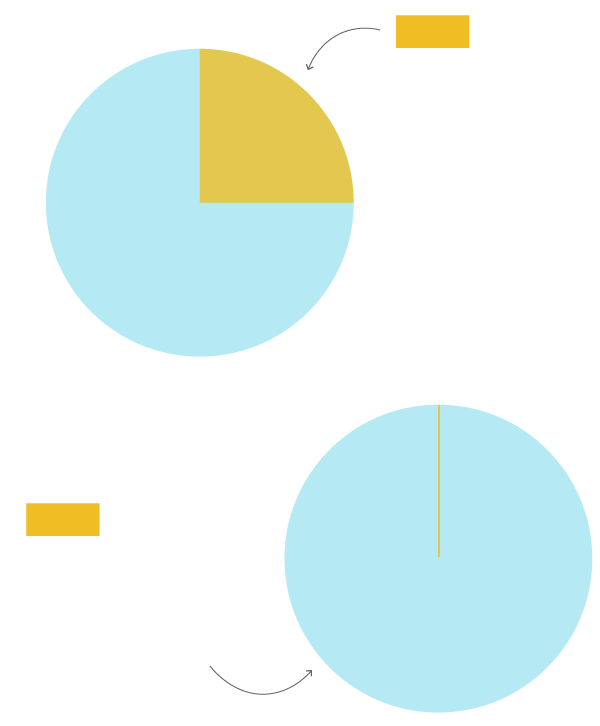

In 2019, Muni accounted for more than 25 percent of all the recorded trips in San Francisco. That same year, it also accounted for three-hundredths of one percent (0.03 percent) of the greenhouse gas emissions from transportation in the city.

Three-hundredths of one percent is small. But the true number is actually even smaller. That’s because transportation is just one of many sources of greenhouse gas emission in San Francisco. According to 2020 data, “transportation” accounted for 44 percent of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions (“Buildings” also generated 44 percent).

That means Muni is responsible for three-hundredths of a percent of 44 percent of the city’s emissions. Which, doing the math, comes out to only around 0.013 percent of all the emissions.

But wait, there’s more: 2020 was, admittedly, a weird year. Two years later, 2022 was more up to speed. Still, according to the data from ’22, Muni was only responsible for not just a tiny sliver of all transportation emissions but a tiny sliver of all public transportation emissions.

Ferries accounted for 68 times the emissions as Muni. San Francisco’s own municipal fleet of cars and trucks at the disposal of city employees emitted 43 times the greenhouse gases of the transit agency carrying hundreds of thousands of riders daily. And private citizens’ vehicles spewed 3,423 times as much emissions as Muni buses and trains.

The 2022 numbers, like those from two years prior, put Muni’s emissions as around one-hundredth of a percent of the city’s total.

Where is the environmental virtue in saddling Muni with orders to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on upgrades while leaving 99.99 percent of the city’s emissions untouched? There wouldn’t be any.

Muni carried

26% of trips in

S.F. in 2019

The same year,

Muni accounted

for 0.03% of

transportation

emissions in S.F.

Public transit can be complicated, but this much isn’t: The cleanest bus, again, is a full bus. Muni’s diesel buses have gone gentle into that good night — replaced by diesel-electric hybrids. Our trolley buses run on Hetch Hetchy hydroelectric power, as do the light-rail vehicles and trams. San Francisco has 12 battery-powered buses. Cable cars, we are told, run on dilithium crystals. There are not a lot of emissions there to reduce.

San Francisco is a city that really shouldn’t be encouraged to gloat about its bona fides. But, in Muni’s case, we’re doing pretty well here. But we could screw that up. In some ways, we already are.

Ostensibly smart people have said that the solution to San Francisco’s transit ills will come via thousands and thousands of autonomous vehicles being deployed to the city. That may happen anyway, and the AVs on city streets today are, by and large, low-emission compared to other private vehicles.

But the congestion, if this becomes more widespread, will be immense. There’s a reason transit times in San Francisco are often no better than they were more than a century ago when people took their deceased relatives to the graveyards of Colma via rail: Congestion has exploded in the era of ubiquitous private automobiles — which also accounts for the plurality of city greenhouse gas emissions.

“You want to get people out of their cars and encourage transit-use,” says Khatri. “Well, that is also the best way to reduce emissions.”

The best way to get people out of their cars is to have safe and reliable transit nearby and running frequently. Muni should be given free rein to better achieve this until such time as it can afford to be a caravan of perfect virtue. Anything else would be insaaaaaaane.