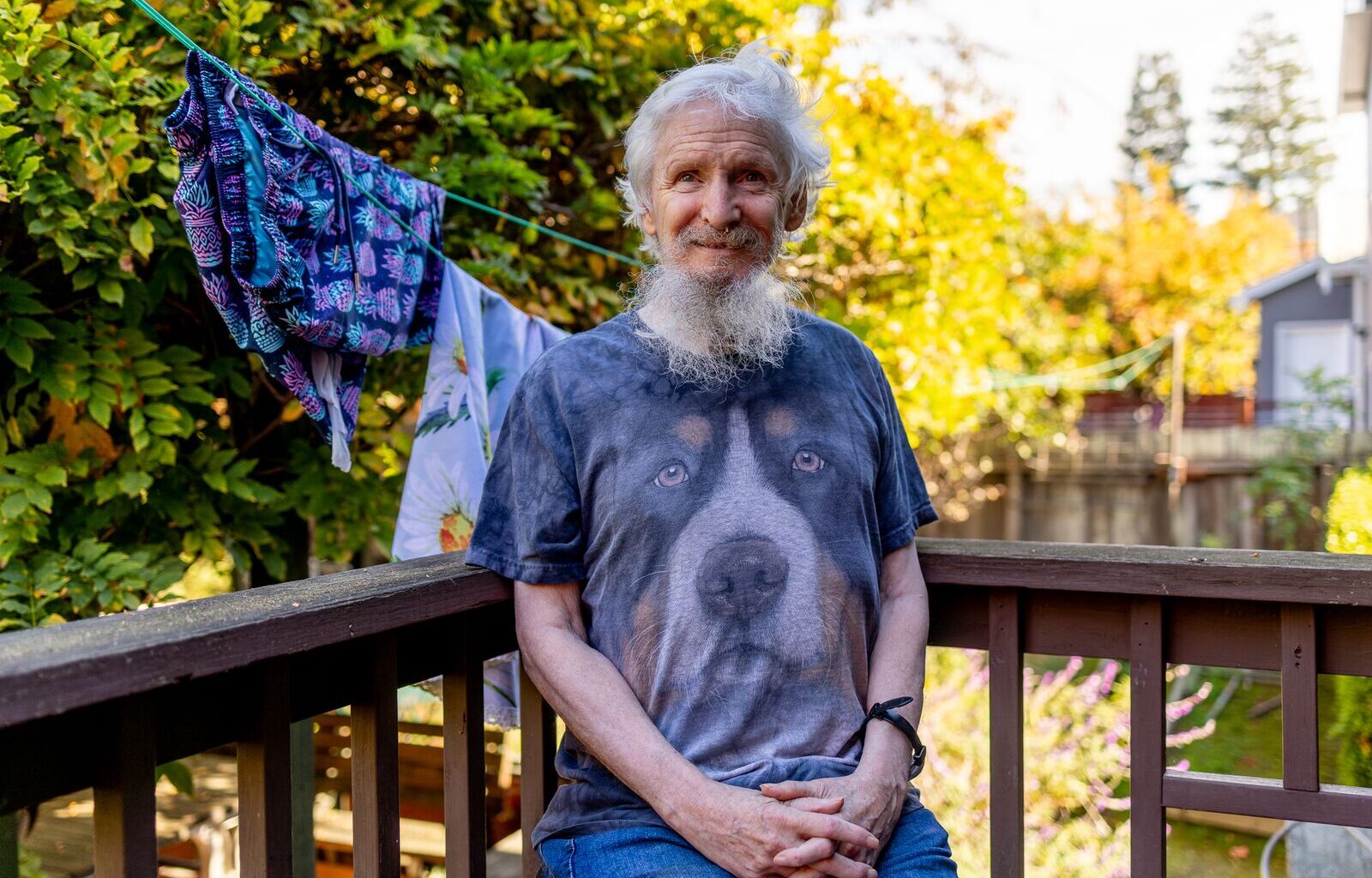

The author, Dirk Neyhart, at his home in north Berkeley. Credit: Sarah Martin

The author, Dirk Neyhart, at his home in north Berkeley. Credit: Sarah Martin

I grew up here in Berkeley but was born south of the border, in Oakland [laughs]. My first house in Berkeley was by Indian Rock on San Mateo Road, and I went to Cragmont Elementary. Then my parents moved above Grizzly Peak in 1960. I’ve been in my current house in North Berkeley, which my late wife Patricia bought in 1979, for about 30 years.

When I was growing up, people liked to join. People joined churches or clubs or dance groups or singing groups. Those still exist, but their membership has quite declined. People just don’t want to join anymore. It’s certainly down from the ’50s and ’60s. And before, if you got on the bus you could say hello to everyone. Now, if you did that, they’d rush you off to the looney bin. It’s a sad state of affairs.

Amplify Berkeley is our new series featuring stories told by Berkeley residents in their own words. Got a story to tell? Let us know.

I went to Cal from ’65 to ’70. Being a student at that time was tough, or at least it was tough for me. In high school, if I studied three hours a day I thought I should get a gold star. But when I got to Cal, I was competing with kids who could study for 10 or 12 hours a day.

I started off in chemistry and did poorly. I went into biochemistry and did poorly. Then I went into computer science and got straight A’s, then concluded with economics. I was at Cal for six years because I was trying to stay out of Vietnam; it wasn’t necessary to murder innocent people if you were in school.

At the time, I was commuting a lot between Berkeley and San Francisco or Sausalito, where I lived for a while. Once I started doing computer science I rented an apartment in Berkeley — just a closet — so I could get to the computers on campus in the middle of the night. Quick turnarounds were only available for computer programs. For an undergraduate student, the computers were only available between midnight and 4 a.m. Otherwise, you might have to wait two days to get a program processed.

My favorite place on campus was the Morrison Library where you could put on headphones and listen to classical music and study. Otherwise, I was always at La Val’s on Euclid or Caffe Med on Telegraph. I liked Cody’s Bookstore.

I think people were more engaged in those days; people were earnest. I went to protests — I certainly had longer hair than a Marine — but I wasn’t involved in organizing. Cal had good professors, and our job as students was to be inspired by what they had to say.

After graduating, I looked in the job ads and learned I could be a Yellow Cab driver and make $100 or more a week, a princely sum at that time. So, to the disgust of my Harvard-degreed parents, I became a cab driver and had bucks in my pocket every day. Life was good.

Over time I became a shop steward and a labor organizer for the Teamster’s Union, but I kept losing in my efforts. People said, “I don’t care about pensions, I don’t care about seniority, just give me 30 cents more an hour in my pocket.” Eventually, I thought, “If I can’t beat them, let me join them,” and so in 1982 I became a stockbroker.

Fifteen years later, in 1997, my life took a very different turn. I had picked up a hitchhiker in San Francisco wearing Army fatigues who was smiling and holding up a sign saying, “Berkeley.” I used to hitchhike myself, so I have great sympathy. We got to Berkeley and I was looking for a place to let him off and pulled into a gas station at 6th and University. It was very late at night.

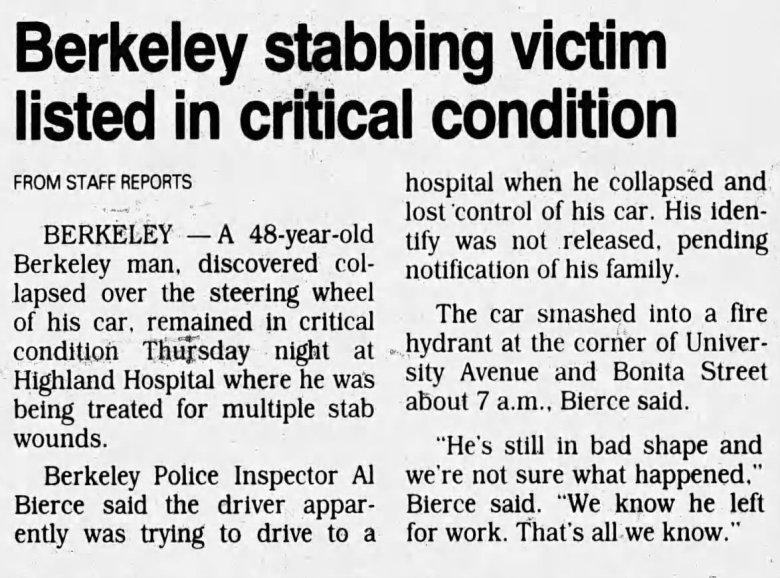

That was the last I knew until five months later, when I was released from the hospital. He had stabbed me all over and left me to die on University Avenue. I couldn’t remember anything except his clothes and that he was a man, so he was never caught. When I got to Highland Hospital, they said I was flat-lined. But the surgeon opened my chest and massaged my heart and the monitors began to flicker, so here I am.

A crime brief in the Oakland Tribune on Jan. 3, 1997 describes a stabbing on University Avenue in Berkeley, confirmed by the author, Dirk Neyhart, to be the same incident that left him disabled. Source: newspapers.com

A crime brief in the Oakland Tribune on Jan. 3, 1997 describes a stabbing on University Avenue in Berkeley, confirmed by the author, Dirk Neyhart, to be the same incident that left him disabled. Source: newspapers.com

During my five months in the hospital, I had to learn how to eat, talk and walk all over again. You could say I still haven’t relearned how to do all those things [laughs].

Accommodating any disability presents challenges, but we’re genetically programmed to conquer adversities. I went to a school in Albany called the Orientation Center for the Blind, and learned how to be blind. I learned how to read Braille and use screen readers for computers. I learned how to cook and be an independent person like I was before.

There are so many places and people here to help. It’s wonderful. Places like the East Bay Center for the Blind, the Ed Roberts Center, The Lighthouse for the Blind, and all the special education teachers and health professionals who work with the disabled. I work with personal helpers, like Jason, who assist me from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Of course, being disabled in Berkeley is still difficult. I used to be able to take buses. Now due to decrepitude — from the injury or age or laziness — I’m unable to walk two blocks. I’ve never been fearful of going out, and people are generally kind. But my body won’t cooperate, so buses are out of scope for me. I will take cabs or paratransit, depending on the distance.

Accommodating any disability presents challenges, but we’re genetically programmed to conquer adversities.

Recently, the city’s paratransit voucher program was decreased from about $600 to less than $300 a year. I’ve sold enough pencils in my life to still afford to go to yoga class, go to my appointments. But for others, especially seniors, the cost keeps them at home. This is an issue of great importance. Politicians here and in Sacramento should fund more paratransit.

Still, isn’t it wonderful that in Berkeley, we do have a good paratransit system? Not great, but better than none.

I devote most of my time in my forced retirement to giving back. I’m on the board of four nonprofit corporations, all of which would welcome more money and energy in 2026: the United Nations Association East Bay Chapter, the East Bay Gray Panthers, the Berkeley Lions Club, and the Lions Vision Resource Network. Each has a mission to serve, and we try to find things to do in Berkeley that will make the community a better place.

A plaque that was presented to Dirk Neyhart from the Berkeley Lions Club hangs on the wall of his north Berkeley home. Credit: Sarah Martin

A plaque that was presented to Dirk Neyhart from the Berkeley Lions Club hangs on the wall of his north Berkeley home. Credit: Sarah Martin

And then there’s politics; I’ll get involved in campaigns and I’ll occasionally listen to Berkeley City Council meetings. Sometimes only half a dozen people will come to the meeting to speak about a council measure that might affect the pocketbooks or the happiness of a large segment of our community, and that can be disappointing. So I spend time going to a lot of meetings. Happily, it’s easier now with Zoom.

I’ve been around much of the world — Canada, Mexico, Africa — and I haven’t found a place better than Berkeley. Where else can you have good medical care, work, good intellectual opportunities, the snow a couple hours away and hot weather a couple hours away? Another joy is the food, all the wonderful restaurants. I have a nice neighborhood, and that’s a source of community. The Quaker meeting house on Walnut and Vine is another. And then I have my group of blind friends.

So bravo, Berkeley. This is, in my experience, the best place to live.

“*” indicates required fields