The United Educators of San Francisco, which represents more than 6,500 public school employees, is moving closer to a strike.

The union is holding a second vote, required to authorize a strike, at every school site throughout the city each day from now until Jan. 28. More than 99 percent of union members who voted in the first round in December said yes. If need be, they’re ready to launch the district’s first strike in nearly 50 years.

It would come at a fraught moment for SFUSD, which is proposing another year of cuts and could revisit school closures, all to address a deficit brought on by years of fiscal mismanagement and a steady drop in enrollment.

A strike is “a very likely possibility if the district doesn’t change course,” union president Cassondra Curiel told The Frisc last week. She said the union has nothing new for the bargaining table, but “would encourage” SFUSD to reconsider “if they want to avoid escalations.”

The union is demanding pay raises, better healthcare benefits, and help for special education teachers. The district is trying to close a deficit predicted to hit $103 million over the next three years.

After ten months of bargaining, the two sides jointly declared a stalemate in October, which meant the California Public Employment Relations Board (PERB) assigned a neutral third-party mediator. But so far, it hasn’t helped. Last Friday, PERB’s “fact-finding” representative conducted one last mediated effort with the two sides to try to broker a deal.

Nothing came of the meeting. PERB now plans to release a public report by Feb. 4 with their findings. Once this report is public, the union can legally go on strike.

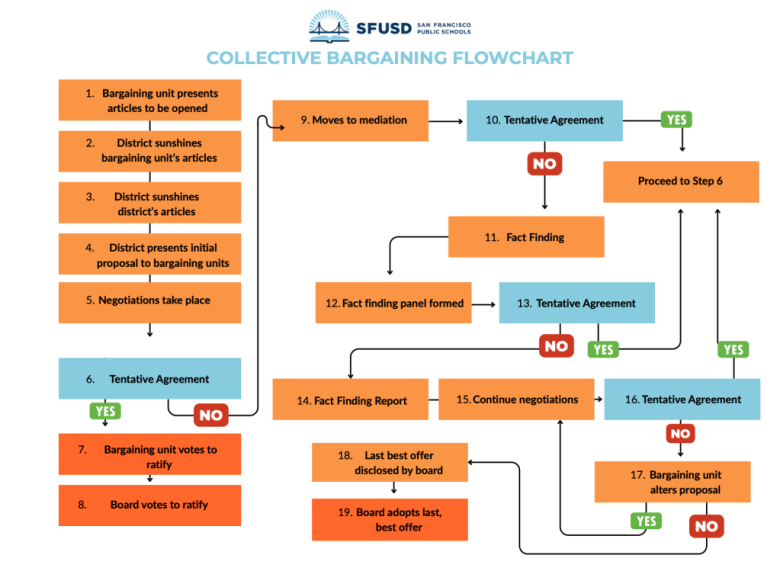

District spokespeople declined to comment for this story and pointed The Frisc to bargaining updates on the website and a flow chart to explain negotiations. School board president Phil Kim also declined to comment.

Raise rates

“While SFUSD deeply values its educators, the district is also grappling with a dire fiscal reality,” the district’s website says. Union reps are skeptical.

“We hear this every year,” said Ryan Alias, a Balboa High School English teacher and part of the union’s bargaining team.

The collective bargaining process; after an unproductive fact-finding session, the California Public Employment Relations Board will release a report (step 14) on Feb. 4. Teachers could strike that day. (SFUSD)

The collective bargaining process; after an unproductive fact-finding session, the California Public Employment Relations Board will release a report (step 14) on Feb. 4. Teachers could strike that day. (SFUSD)

The previous contract, which expired in June, gave UESF a $9,000 raise in 2023 and a 5 percent raise over the following two years. For the next two-year contract, UESF wants an annual raise of 4.5 percent divide over two years for certificated employees (teachers, nurses, counselors, and other roles that require a credential), and a 14 percent bump for classified employees — clerks, technicians, and others who don’t need a credential.

The district’s counteroffer is a 2 percent bump for certificated and classified employees each year for the next three years. In exchange for the raise, the first round of which wouldn’t meet this year’s federal cost of living adjustment, the district wants to cut paid leaves, prep periods for some teachers, and stipends for department heads. It also wants to expand class size limits. The union called the counteroffer insulting.

According to the district, the parties reached a tentative agreement in October on a handful of smaller issues, but they haven’t budged on pay or the union’s other key demands.

Under the state microscope

Because of the district’s financial situation, the California Department of Education (CDE) has partial control of its monetary decisions. CDE won’t lift oversight until SFUSD proves it has reached a certain level of stability, which the district hopes to do by March. Part of a longer-term plan are proposed cuts starting next school year that would save the district $8.6 million. They include assistant principals, mental health workers, and security guards. Principals have until the end of January to make a case for other options.

Meanwhile, CDE can veto any financial decision it deems harmful to the district’s budget — including pay raises — even if the consequences are painful. In 2024, the state demanded a hiring freeze which “absolutely impacted our schools, and was very frustrating for families,” said Meredith Dodson, executive director of San Francisco Parents Coalition.

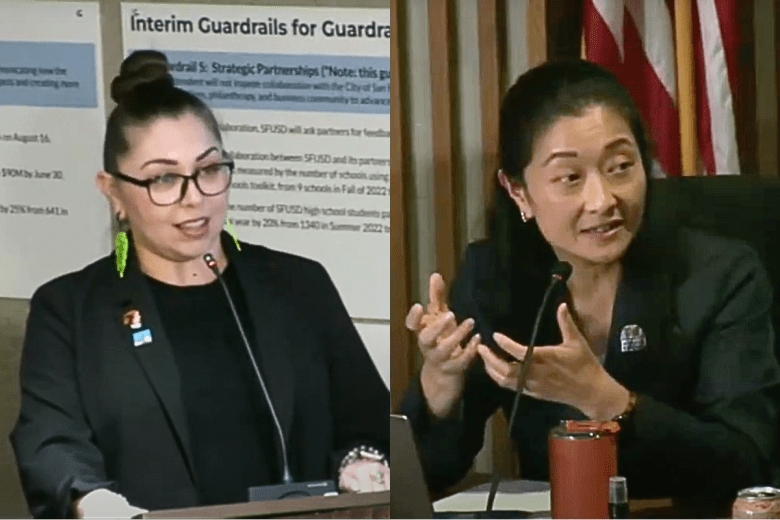

Negotiations have stalled between UESF (President Cassondra Curiel, left) and SFUSD (Superintendent Maria Su, right). The California Department of Education has the power to veto any financial decision deemed harmful to the district’s budget. (San Francisco Unified School District)

Negotiations have stalled between UESF (President Cassondra Curiel, left) and SFUSD (Superintendent Maria Su, right). The California Department of Education has the power to veto any financial decision deemed harmful to the district’s budget. (San Francisco Unified School District)

CDE advisor Elliott Duchon, who has been working with SFUSD since 2021, did not answer requests for comment.

Union president Curiel questioned how state oversight has helped: “The state is also responsible for allowing this to occur year over year. This is not the first time that we heard it’s a crisis.”

The district is also proposing an 8-percent reserve fund of around $111 million for “economic uncertainty,” which did not sit well with the union and its backers. “We know the district is sitting on a surplus, a rainy day fund,” said Alias. “It’s raining now.”

Alias said the union’s demands fall well under this surplus amount, but the union hasn’t made those figures public.

According to Chris Mount-Benites, deputy superintendent of business operations, this reserve fund is intended to cover two months of operations in case of emergency — for example, should the state face a crisis and delay the money it gives the district. Most districts keep a reserve roughly twice what SFUSD is proposing, he said.

Healthcare and special ed

Millions of Americans have to tighten their belts with Affordable Care Act subsidies expiring this month. Educators in San Francisco are asking for fully funded dependent healthcare. Their last contract covered 65 percent for one dependent and 53 percent for two dependents.

For a family with two kids, healthcare premiums are roughly $1,200 every month and will soon increase to roughly $1,500.

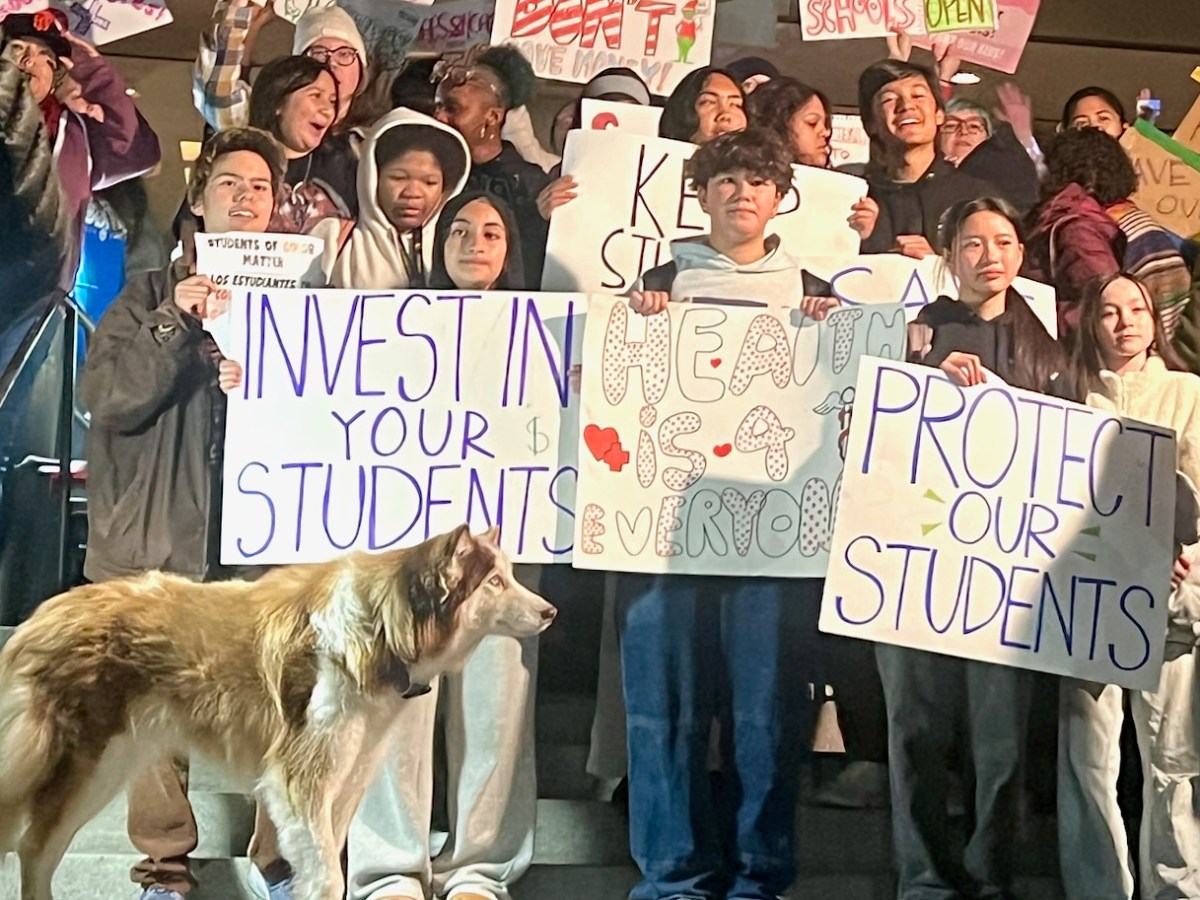

A UESF rally outside the SFUSD headquarters before the Oct. 14 school board meeting. They want fully funded healthcare like other Bay Area schools.

A UESF rally outside the SFUSD headquarters before the Oct. 14 school board meeting. They want fully funded healthcare like other Bay Area schools.

Employers don’t typically cover 100 percent of family healthcare premiums, according to a 2025 KFF survey of California benefits. But there’s precedent in education. Eight unions last month reached a tentative agreement with the LA Unified School District for fully funded dependent healthcare.

“We are looking to neighbors like Oakland and San Mateo who already have it, as well as Richmond … as inspiration,” California Teachers Association spokesperson Jessica Beard told The Frisc via email. After Richmond teachers struck for four days last month, West Contra Costa Unified School District agreed to pay 100 percent by 2028.

SFUSD said last week that it proposed a way to fully fund family benefits as part of a broader package that UESF rejected.

UESF is also asking for an overhaul of special educator workloads. Right now, the district creates schedules based on the number of cases, not the hours each kid needs. The union says this is a problem because some kids need more time and resources than others, and educators are burning out.

‘They always come to me’

It’s also contributing to a staffing shortage. One of the two special-ed classrooms at Sunnyside Elementary hasn’t had a fully credentialed teacher for more than a semester at a time in the last three years, according to multiple teachers there.

Cynthia Payne runs Sunnyside’s other classroom; three of her students are on a feeding tube, one uses a gastronomy tube, and one needs extra supervision because of seizures. Some also have behavioral challenges and cognitive delays. Payne often works with a nurse.

She also often takes on work for the other classroom. “If something happens in there, they always come to me,” said Payne. She has created lessons, restocked supplies, and even met with parents of kids who are not in her class.

“I feel like, if I keep doing it, then why would they hire a teacher?” she told The Frisc. “I’m considering not coming back next year. I hate to do that to my students, but it’s just not sustainable.”

The school board regularly asks the state for help finding extra special educators, most recently last month.

UESF wants to hire a specialized attorney as part of increased support for immigrant students. SFUSD says immigration issues fall outside the scope of collective bargaining. (Photo: Taylor Barton)

UESF wants to hire a specialized attorney as part of increased support for immigrant students. SFUSD says immigration issues fall outside the scope of collective bargaining. (Photo: Taylor Barton)

UESF also wants more support for immigrant students and homeless families. Immigration issues fall outside the scope of collective bargaining, SFUSD spokesperson Laura Dudnick told The Frisc in October. What’s known as “bargaining for the common good” is “not outside the ordinary at all,” according to UESF’s Alias. LAUSD included language supporting immigrant students and families in their 2022-25 contract with teachers.

As with other demands, the cost to the district is up for debate. Educators want “at least one attorney to address immigrant-related concerns,” plus staff training on interactions with law enforcement. Some of this training is already happening, but educators want more. Alias pointed to local nonprofits with “proven track records” that are “waiting in the wings to expand.” He wasn’t sure if an expansion would be on the district’s dime or pro-bono from external partners.

SFUSD already runs one overnight shelter for its homeless families. UESF wants to protect the program by including it in their contract. Keeping what’s in place wouldn’t cost more money, but the union’s request to create at least two more shelters at other sites might.

Pandemic flashbacks

Andrea Pereira, here with her kids Jack and Gloria, supports a strike. “My kids have incredible teachers,” and their healthcare situation is “totally unacceptable.” (Photo: Taylor Barton)

Andrea Pereira, here with her kids Jack and Gloria, supports a strike. “My kids have incredible teachers,” and their healthcare situation is “totally unacceptable.” (Photo: Taylor Barton)

One parent who supports a strike is Andrea Pereira, who brought her two SFUSD kids to a recent union event to help build picket signs. “My kids have incredible teachers,” and their healthcare situation is “totally unacceptable,” said Pereira.

The threat also brings back memories of COVID. “We saw this during the pandemic,” said Dodson of SF Parents Coalition. “Any kind of disruption to students’ learning that can be avoided, we want to avoid if we can.”

“We all support fair pay and good working conditions to be able to attract and retain the teachers we want here for our kids,” said Dodson. “At the same time, we also understand the difficult budget situation that the district has been in for years.”

She added that a strike seems likely, and the impact would be greater on families whose adults “don’t have the luxury to just be home with [their kids].” More than 55 percent of SFUSD families are socioeconomically disadvantaged, according to the state.

During COVID, with schools closed and classes on Zoom for more than a year, the city’s Department of Children, Youth, and Their Families (DCYF) set up supervised centers for students. When asked if DCYF would take similar steps, a spokesperson said in part that the department is aware of the possibility of a strike and is “assessing potential needs.”

It will likely be difficult for educators, too. Union members don’t get paid when on strike. The union doesn’t have a strike fund, but it does have money to support a limited number of members “experiencing financial crisis.”

“It’s going to disrupt the everyday operations for the entire city,” said Alias. But “it has become increasingly clear that it’s the only way the district is ever going to take us seriously.”

More from The Frisc…