This series, Broken Promises, will explore the loss of these spaces in Long Beach, the impact on the surrounding communities, broken promises from the City and what local residents are doing to preserve what little is left.

Read the first chapter here.

Read the second chapter here.

Pacific Place project – the plan to turn 14 acres of open space near the Los Angeles River into an RV, self-storage facility – has sparked concerns for West Long Beach residents, environmental groups and public agencies.

West Long Beach is already running low on undeveloped green spaces, as well as park equity, with about 1.5 acres per 1,000 residents, according to a city report in 2022. Many residents have long expected 3701 North Pacific Place to become a park. Instead, it has sat as a vacant lot, formerly an oil brine facility in the 1920s and later a golf course until about 2015.

Pacific Place was among several areas Long Beach had highlighted as opportunities for green space, with plans to restore native habitats and improve pedestrian and bike pathways. The site was also recognized by the LA River Master Plan and the Lower LA River Revitalization Plan, which ranked Pacific Place as a site with “high potential” for habitat conservation, improved environmental quality, community green space and more.

However, these hopes were crushed when developers purchased the privately-owned site and made a proposal in 2020 that would transform the property into a four-story, self-storage facility with office spaces, an RV parking lot and a car wash. The City approved the project later that year, sparking outrage from the community.

Residents display signs in their front yards against the approved project at Pacific Place in a neighborhood between Bixby Road and Country Club Drive on Nov. 11, 2025, in support of the Riverpark Coalition. The “parks not pavement” motto refers to recently-approved plans to build a car wash, office buildings and RV parking lot in a space once slated as public park space for West Long Beach residents. (Jorge Hernandez | Signal Tribune)

Residents display signs in their front yards against the approved project at Pacific Place in a neighborhood between Bixby Road and Country Club Drive on Nov. 11, 2025, in support of the Riverpark Coalition. The “parks not pavement” motto refers to recently-approved plans to build a car wash, office buildings and RV parking lot in a space once slated as public park space for West Long Beach residents. (Jorge Hernandez | Signal Tribune)

Years later, the City released its draft environmental impact report (EIR) in July 2024 – after LA Waterkeeper won a lawsuit demanding the City conduct a full report under CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act). The report analyzed the project’s impact on the surrounding environment and ways to mitigate possible damage. Over 60 people, including public agencies, environmental groups and concerned residents, submitted comments to the City with concerns about the project’s impacts on flooding risk, air pollution, contaminated soil and native vegetation.

Several West Long Beach residents expressed anger, disappointment and frustration in their letters, questioning the City’s decision to choose development over green space, and its negative impacts on the community.

“Currently in north Wrigley, youth don’t really have a nice wide open space to play sports or do outdoor activities. …. It would be great to give these families a great green space to make lasting memories together that is actually safe. So many of the new families in Wrigley have young children who deserve to play in an area where their parents don’t have to worry about cars,” resident Gabrielle Sibal said.

Want more local news?

Sign up for the Signal Tribune’s daily newsletter

Some also felt a sting of betrayal, as they felt the City had broken its promises to the community.

“As Long Beach grows, trying to be a jewel for families to flock to, why on earth would families chose to move here? Why should I continue to grow my family here? Why should I stay in Long Beach when my city government backtracks on promises. How do I know my tax dollars are going where they were promised? Should I expect only dishonesty and false promises from city officials or should our city run to a higher standard? Further, why would any family want to live near an old oil operations field that wasn’t properly cleaned up risking toxic substances so close to Cerritos Elementary school? Has the children’s health been considered at all?” Resident Emma Corman said in her letter.

In the final EIR released in May 2025, the City responded to these concerns, often referring people back to the draft EIR, where they detailed strategies to mitigate environmental damage.

However, many residents and nonprofit groups like Riverpark Coalition and LA Waterkeeper were left dissatisfied with the City’s answers.

The two groups sued Long Beach for the second time last September, claiming the final EIR lacks evidence to support its claims and “fails as an informational document.”

The Signal Tribune read through the lawsuits, both EIRs and letters from residents to break down each environmental concern and the City’s response to it.

Flooding Risk

Due to its proximity to the LA River, Long Beach is perpetually at flooding risk, along with other cities in LA County the river bisects.

The city sits on a floodplain that used to receive catastrophic flooding in the 1930s prior to its channelization. Due to Long Beach’s location at the end of the 51-mile river, where it receives the collection of all the runoff from the Los Angeles Basin, many parts of the city are still at risk.

Benjamin Harris, senior staff attorney for LA Waterkeeper, said the Pacific Place project exacerbates flood risk by taking away safely floodable space and adding a new structure that now needs protection from flooding.

“Every land use decision that’s made in the LA River watershed, and especially along the LA River channel itself, is really critical. Every building that we build next to the river is another building that needs to be protected from future flooding, and it’s also taking away the opportunity to use that site to mitigate flood risk.”

Benjamin Harris, senior staff attorney for LA Waterkeeper

Although the river does not regularly overtop during storms due to it being surrounded by concrete, it’s possible that severe flooding could occur every 100 years, according to a study by UC Irvine.

The study, which used a flood risk modeling system, named Long Beach as one of the most severely exposed areas in a 100-year flood zone.

Areas of West Long Beach and Signal Hill – including the area where Pacific Place lies – could be subject to over 5 feet of flooding in a 100-year event, according to the study.

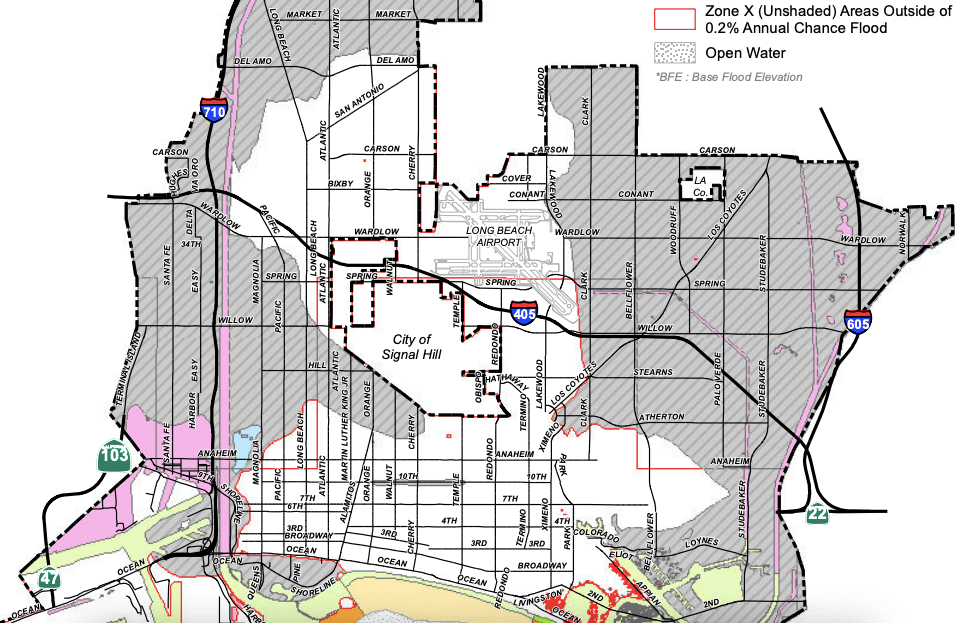

The FEMA flood zone map shows the areas in Long Beach along the Los Angeles River are all at the highest risk of flood zone. (Courtesy of the City of Long Beach)

The FEMA flood zone map shows the areas in Long Beach along the Los Angeles River are all at the highest risk of flood zone. (Courtesy of the City of Long Beach)

Harris said that if the area were to be turned into a park or green space, it could help mitigate flood risk by retaining water that would otherwise go into the river. A park could also become a safely floodable space, instead of houses or buildings taking the damage.

“A lot of the communities along the LA River have much more pronounced flood risk than other communities in the LA area because they are right next to a channel that theoretically could overtop in a large storm,” Harris said. “There’s a connection there between living near the river and having [a] more pronounced flood risk.”

In response to this concern, the City said it would implement an on-site water treatment system to combat runoff and flooding, including a biofiltration system and stormwater detention system to capture surface runoff on site, treat it and release it into the municipal stormwater system. The system would also direct onsite drainage to underground storage pipes, store stormwater and release it into municipal storm drains “at a controlled rate.”

However, one comment on the draft EIR pointed out that this system fails to account for “future increases in stormwater due to climate change.”

The City said their system’s pipes would have a capacity for 33,499 cubic feet per second (cfs) and 15,988 cfs, which is greater than the required amount set by the City. As there is no requirement to exceed this design criteria, they do not plan to account for more stormwater, they said in response to the comment.

Fire Risk

Several residents have also raised concern over the site’s potential fire hazard, due to the presence of hundreds of RVs and the site’s proximity to the Newport-Inglewood Fault.

If there were to be an earthquake, for example, the RVs could rock or slide, causing the propane tanks to potentially break and leak, catching on fire and quickly spreading to other RVs. Furniture or kitchen appliances could also slide and pull on gas lines, causing a leak inside an RV.

There have been instances in the past where an improper propane installation led to an RV explosion, or a fire broke out in an RV park, spreading quickly and causing propane tanks to explode.

“Just if one [RV] becomes a fire issue, it could be a fireball over there,” said Leslie Garretson, board president of Riverpark Coalition.

However, the City said vehicle fuels and materials associated with vehicle maintenance would comply with city regulations, that workers would be trained to contain or clean up “small spills of hazardous materials” and that the site is not located in a designated high-risk fire hazard zone.

A car drives past the dirt mound at the proposed site for the Pacific Place Project. (Richard Grant | Signal Tribune)

A car drives past the dirt mound at the proposed site for the Pacific Place Project. (Richard Grant | Signal Tribune)

Air Pollution

Pacific Place lies on land that ranks in the 89th percentile for pollution, according to California’s CalEnviroScreen tool, meaning it’s in the top 11% most polluted sectors in the state.

Several residents are concerned the project would only worsen air pollution in West Long Beach by blowing up toxic dust from the site’s contaminated soil into local neighborhoods, as well as increasing RV vehicle emissions.

In LA Waterkeeper and Riverpark Coalition’s lawsuit, they claim the project’s NOx (nitrogen oxide) emissions during the construction phase would result in concentrations that violate California and federal 1-hour air quality standards. Areas surrounding Pacific Place would be exposed to these pollutants for the duration of construction, the lawsuit says.

However, the City says the project’s activities will not involve industrial uses “that would generate a significant amount of toxic air contaminants.” They also said the project’s air emissions are “well below SCAQMD thresholds.”

A sign warns about the levels of lead and arsenic that are in the soil at the proposed site for the Pacific Place Project. (Richard Grant | Signal Tribune)

A sign warns about the levels of lead and arsenic that are in the soil at the proposed site for the Pacific Place Project. (Richard Grant | Signal Tribune)

Toxic soil

Due to the site’s history as an oil brine and drilling facility, Pacific Place is known for its heavily contaminated soil. Without a remediation process, some residents are concerned about this toxic soil remaining on site.

The City acknowledged in its mitigated negative declaration that the site had undergone various assessments to confirm the soil was contaminated.

In response to these concerns, the City said it had mitigation measures in place, such as requiring project developers to remediate the site and monitor the exposure of these toxins.

However, the technique laid out in the EIR involves “trapping” the contaminated soil with a layer of clean soil, concrete and other materials.

While this prevents human exposure to the toxic soil, many residents argue this is not a good long-term solution, as the toxic soil remains underground and the barrier could be ruptured by an earthquake, for example.

LA Waterkeeper also pointed out in its lawsuit that the City’s response plan seems to only address existing contamination but not the project’s introduction of new possible contaminants.

Biological concerns

Several residents and agencies brought up the concern that project developers had removed over 1,000 native southern tarplants from the site prior to project approval and the environmental report.

In response to the damage, the City plans to install a native tarplant reserve on site, although LA Waterkeeper argues the mitigation plan does not relay specific details on how the plants will be established and maintained.

A Tongva elder lets sage smoke blow across the 4 acres that are soon to be restored and opened to the public. (Kristen Farrah Naeem | Signal Tribune)

A Tongva elder lets sage smoke blow across the 4 acres that are soon to be restored and opened to the public. (Kristen Farrah Naeem | Signal Tribune)

Tribal and cultural concerns

The site is also of cultural and tribal significance to the Tongva people, as a Tongva settlement used to be located along the LA River or near the project, according to a letter sent by Chief Anthony Morales and Rebecca Robles of the Gabrieleno San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians.

Sacred objects have also been found near the site.

In response to this concern, the City said the project would be required to have a tribal consultant to be on site during construction activities, such as excavation. If tribal objects are found during construction, developers must cease activity until the area is assessed.

Morales describes these mitigation measures as “grossly insufficient.”

“The analysis of cultural resources neither acknowledges the existence of nor considers the cumulative impact on these resources,” Morales said in the letter. “The City of Long Beach has not officially recognized any sites honoring the Tongva, not even the National Register site of Puvungna on the CSULB campus.”

Additional concerns

In the final EIR, the City responded to concerns about wastewater treatment and threats to wildlife, including native tarplants, monarch butterflies and the Western Yellow Bat.

LA Waterkeeper and Riverpark Coalition claim in their lawsuit, which they filed last September, that the environmental report is “prejudicially misleading,” lacks evidence to support its claims and “fails as an informational document.”

They claim the City ignored key mitigation measures and that descriptions of off-site improvements were vague. They also said the EIR relies on comparisons to the MND, which was made for an earlier version of the project that had only three stories and less square feet. These MND findings should not be used in the final EIR, which addresses a newer version of the project, they said.

For now, the development is on pause as the organizations continue their fight to preserve this “last gem.”

“There’s tremendous health and safety issues,” Leslie Garretson, board president of Riverpark Coalition, said. “The best use of that land is really not RV parking and storage.”

Angela OsorioReporter

Angela OsorioReporter

Angela is a multimedia journalist and a third-year journalism student at Cal State Long Beach. She has won awards for her coverage of campus government and crime, as well as entertainment stories and print design. Angela is passionate about the role of local journalism in servicing underrepresented communities, and hopes to continue her work reporting on local policy, environmental justice, community solutions and more.