Early voting begins for California’s Prop 50

Early voting begins for California’s Prop 50

California voters will decide whether to change election maps to favor Democrats in congressional elections after Texas approved a redistricting plan which favors Republicans.

OAKLAND, Calif. – States typically redraw their congressional districts every 10 years, following the completion of the U.S. census. But with the Nov. 4 Special Election, Californians are being asked whether to allow for a rare mid-decade action to redistrict.

The proposal, Proposition 50, named for the 50 United States, is being put before voters as a counter response to Texas’s move over the summer to adopt a new congressional gerrymandered map designed to send more Republicans to Washington, D.C. ahead of the 2026 mid-term election.

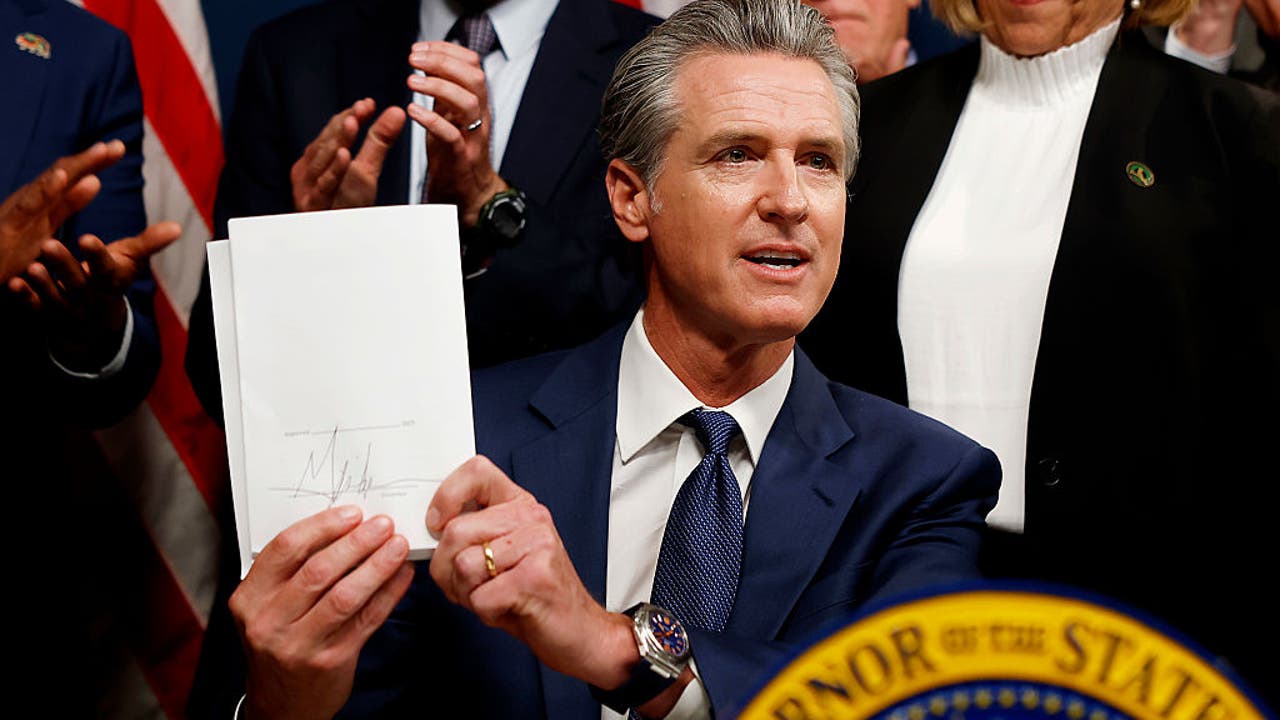

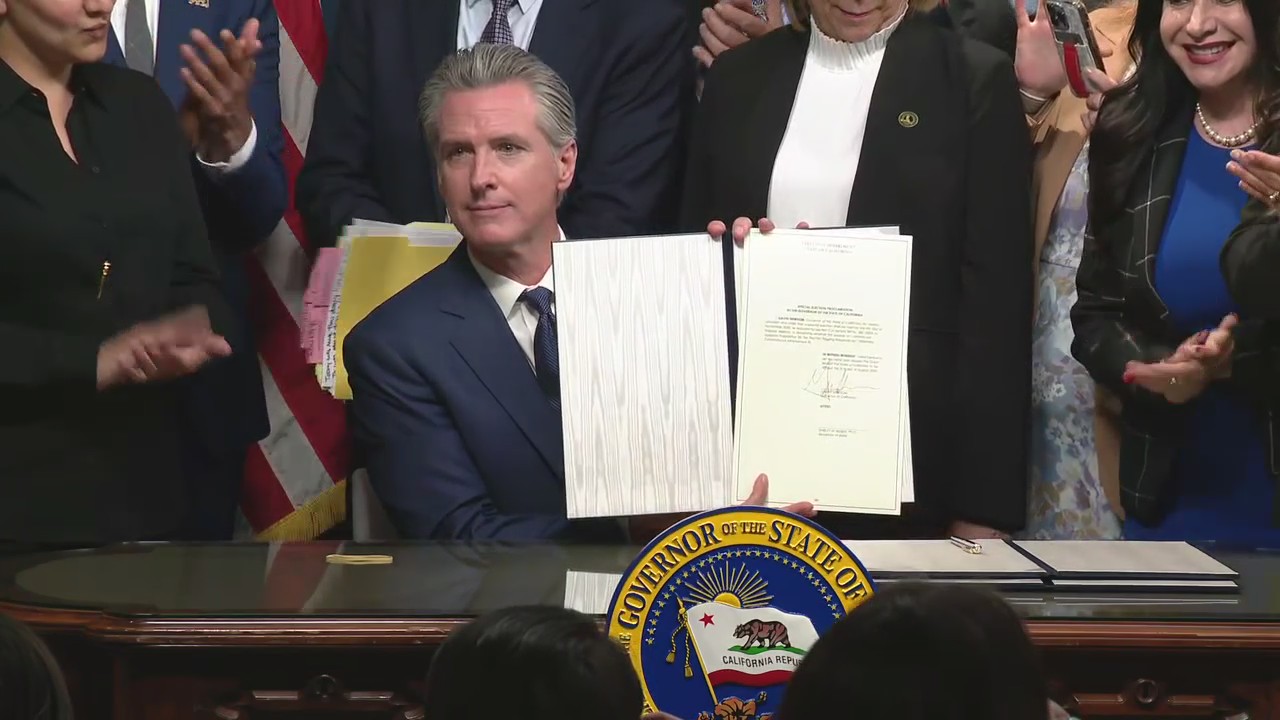

On Aug. 21, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law the so-called “Election Rigging Response Act,” a temporary constitutional amendment he said offers the state an opportunity to “push back against President Trump’s power grab in Texas and other Republican-led states.”

Big picture view:

A yes on Prop 50 would thwart the action of the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, the independent panel tasked with drawing boundaries for the state’s electoral maps every ten years.

It would allow California to make temporary changes to the state’s current congressional districts, with the newly drawn map intended to favor Democratic candidates.

Rare mid-decade action

“It’s rare to see redraws like this,” said Public Policy Institute of California Policy Director and Senior Fellow Eric McGhee, who noted it has not happened in California, at least in the last 50 years.

“Mid-decade redistricting usually happens only when the existing plan has been thrown out for some reason — usually a court decision,” the expert explained, adding that in the early 1980s, a Democratic legislature and governor drew an aggressive partisan gerrymander, a plan which was used only in one election and then struck down in a referendum by voters.

An analysis by the Pew Research Center released in August found that since 1970, only two states had voluntarily moved to redraw congressional maps midcycle as part of a gerrymandering effort.

Texas had done it twice: in 2003 and earlier this year. Georgia redrew its map in 2005.

The Pew Research Center’s figures from August indicated how rare it has been for states to voluntarily redraw midcycle.

“36 of the 40 midcycle redistricting changes since 1970 have either been made in response to a court order (20) or imposed by a court itself (16),” the non-partisan think tank found.

Redistricting battle

Redistricting battle

Now, with the 2026 midterms as its goalpost, a gerrymandering battle has taken shape, with a growing number of states making moves to redraw their congressional districts.

This week, North Carolina joined the redistricting push, approving a new map that would likely give Republicans an extra seat in the House.

“The motivation behind this redraw is simple and singular — draw a new map that will bring an additional Republican seat to the North Carolina congressional delegation,” said GOP Sen. Ralph Hise, the plan’s chief author, outright telling his Republican-controlled legislature that a democratic win in the House will “torpedo President Trump’s agenda.”

SEE ALSO: Rural California leaders say Prop 50 would dilute their voice in Congress

Other states, including Missouri, have also acted to gerrymander its congressional map, a move that’s being threatened with a possible referendum. Ohio and Utah have been engaged in an ongoing redistricting process that was underway before Trump’s second term in office.

The backstory:

While rare in modern history, the voluntary practice of redrawing maps was a more common tactic in the 19th century.

According to Congress.gov, the first example of mid-decade congressional redistricting may have been in New York, dating back to 1804 and 1808 during which new congressional district boundaries were drawn, unrelated to any population shifts.

The U.S. government website also cited the example of Ohio, which drew congressional district boundaries seven times from 1878 and 1892 as the state held “five consecutive House elections under different district maps.”

Experts said that during the 20th century, midcycle redistricting was rarely used, but after the 2000 census, the country saw “renewed mid-decade congressional redistricting activity.”

No federal ban on mid-decade redistricting

Dig deeper:

Texas’s effort in 2003 to redraw maps led to a 2006 Supreme Court case, in which justices ultimately determined that redistricting mid-decade is not unconstitutional on its own.

But the ruling also left some ambiguity on the subject of political gerrymandering.

“They said we’re not sure if partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, but it might be, and we just haven’t seen a good test that would determine which things are gerrymanders and which aren’t, but it left open that possibility,” McGhee explained, adding, “So it provided the potential for the courts to get involved and the potential for guard rails. And I think that held people back a little bit. Obviously, it didn’t end the partisan gerrymandering completely, but it had this looming threat of a court intervention as a potential constraint.’

How we got here

But then in 2019, the Supreme Court decided not to get involved in political gerrymandering at all in the landmark Rucho v. Common Cause case, stating that “partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

McGhee said that ruling, along with the current administration’s overt influence, “a nudge from Trump, who really wants to exploit every advantage that he can,” have drastically changed the landscape to what’s considered unprecedented in modern U.S. history.

“There’s no federal court guard rails, and they got an urging from the president himself, they feel like they have a free hand to dive in,” the PPIC policy director explained.

State level guardrails

California is one of eight states, along with Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, New York and Washington, that use independent commissions to draw congressional districts, in an effort to prevent gerrymandering by elected officials.

The California Citizens Redistricting Commission was established with the passage of Proposition 11, also known as the “Voters FIRST Act” in 2008. In 2010, a constitutional amendment extended the commission’s responsibilities from drawing state legislative districts to include House seats.

The voter-backed commission emerged from decades of redistricting conflict in the state, according to McGhee.

Under Prop 50, the legislatively drawn congressional district maps would be used for the 2026, 2028, and 2030 congressional elections.

The newly drawn temporary map, which could potentially lead to five additional Democratic seats in the House, would expire after the 2030 census, when the commission would resume its authority to draw congressional districts.

New era?

New era?

But the redistricting train may have already left the station, and a new era could be upon us.

McGhee noted that Texas and then California’s reactive move to redraw their maps would, in the big picture, not make a huge difference.

“California and Texas by themselves, are kind of small potatoes,” he said. “It’s not going to change the dynamic nationally that much. What will potentially have a bigger impact is this kind of spiral where more and more states get involved, and then you could start to get into some real numbers that might tilt things.”

And if the Supreme Court decides to throw out the remaining core of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the landmark civil rights law that prohibits racial discrimination in voting, the impact could be profound.

“That would open up a whole bunch more districts that are currently off the table because they are mostly majority Black districts, and then some majority Latino districts in Texas,” McGhee explained. “So it’s the potential for this to broaden and that’s something we really haven’t seen.”

McGhee said when looking at how we got here and where we could be headed, it’s also important to think of the bigger context of the political landscape we’ve been in for some time now.

“It’s just how close the House of Representatives is right now and how close it has been for a really long time. So in the modern party system, since the Democratic and Republican parties emerged in like the 1850s, we’ve never seen a period this long where the two parties are this closely contested in the House of Representatives, and that has really put redistricting back on the table,” the expert explained.

For the first time in the modern era, the nation could see the pendulum, which had been relatively held in place since the 19th century, swing back, with states voluntarily redrawing their maps, shifting how states are represented.

“It could make a difference in terms of who wins the House, “McGhee said, adding, “It’s so close, and this kind of thing could actually tip the balance. This is what makes it so tempting to mess with.”