Sacramento – The City of Petaluma issued a lengthy press release last week in an attempt to spin its way out of the “F” grade it earned for ranking dead last among California cities on the California Policy Center’s 2024 Local Fiscal Health Dashboard. Petaluma ranked No. 328 out of 328 cities with reported data.

Petaluma was responding to a growing group of concerned residents who raised questions about the city’s position at the bottom of CPC’s fiscal rankings. Petaluma went on the offensive — blasting the data, the methodology, and CPC — despite the fact that the dashboard ranking is based on audited financials for FY 2024 that Petaluma and other cities submitted to state and federal authorities.

CPC’s Local Fiscal Health Dashboard was designed to fill a void in government transparency data left after the California State Auditor’s Office unexpectedly discontinued its popular Local Government High-Risk Dashboard in October of 2023. CPC’s dashboard uses public data from Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports (ACFRs) that local governments are required to share with the public annually.

The methodology used in creating CPC’s dashboard was developed by the Hoover Institution’s State and Local Governance Initiative for its Stanford Municipal Finance Dashboard, which examines municipal data nationwide. The Hoover Institution’s methodology is based on the State Auditor’s approach, with some changes made to address data availability. CPC expanded on the data to include not just California cities, but also counties and school districts.

“We built the dashboard so Californians can see how their tax dollars are managed — without government spin,” said Will Swaim, president of the California Policy Center. “If Petaluma wants a better grade, it should start by improving its finances, not attacking the data.”

CPC suggests Petaluma use the dashboard information as intended — as an invitation to dig deep and challenge the policies and decisions that have brought the city to its current condition. The dashboard grade provides an indication that if the city adheres to its current decision-making approach, it will only be able to survive through serial tax increases, deferred maintenance, and deteriorating services. Such a result will be unfortunate for the residents and businesses of Petaluma.

Petaluma’s Dashboard Score

Petaluma‘s dashboard score is based on the city’s 2024 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR), the most recent audit the city submitted to the state and federal governments. Petaluma’s “F” grade in 2024 marked a dramatic downturn from its “C” rating in 2022 and 2023. Because CPC’s scoring method has been the same across years, the lower grade suggests a deterioration in the city’s financial condition.

This deterioration is most evident in the decline of Petaluma’s general fund reserves, which is obvious from the audited financial statements it published. A city’s general fund is roughly analogous to an individual’s checkbook.

In its heated press release, the city states: “Experts in municipal finance recommend that cities keep about two months of operating expenses in reserve — roughly 15% — to handle emergencies or unexpected costs.”

That’s a reference to the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) guideline which “recommends, at a minimum, that general-purpose governments, regardless of size, maintain unrestricted budgetary fund balance in their general fund of no less than two months of regular general fund operating revenues or regular general fund operating expenditures” (emphasis added).

Between June 30, 2023 and June 30, 2024, Petaluma’s unrestricted general fund balances fell from $18.5 million to $9.9 million — excluding “nonspendable” amounts which do not meet GFOA’s criteria for being unrestricted. This drawdown was mainly the result of a transfer to a capital projects fund.

As a percentage of general fund spending, Petaluma’s unrestricted general fund balance fell from 29.3% to 13.9%, well below the GFOA guideline of 16.7%. And, as indicated in the City’s press release, Petaluma’s reserve position compares poorly to that of nearby Santa Rosa which reported $152 million of unreserved general fund balances in 2024. The decline in Petaluma’s general fund balance was mirrored by a decline in its governmental funds unrestricted net position, which is the difference between the city’s liabilities and unrestricted assets. This is the value that drives our Net Worth score. It has also been used by former California State Senator John Moorlach to measure fiscal health across governments for many years. (Moorlach is senior fellow and director of CPC’s Center for Public Accountability.)

Between 2023 and 2024, Petaluma’s unrestricted net deficit increased from $51 million to $59 million, placing it further underwater. The city is right to say that net deficits are common across California cities, but some cities are further underwater than others. For example, San Rafael, a city with a similar sized population only has a $6 million unrestricted net deficit.

With respect to pension obligations — the money the city has promised to pay its retired former employees — it is true, as the city says, that these are largely a function of state public employee retirement law as implemented by CalPERS. But that claim ignores a more important fact: Petaluma, not the state, determines its future pension payment obligations by deciding how many municipal employees to hire and how much to pay them. Residents should review Petaluma’s municipal employee compensation at the State Controller’s Public Pay website and make their own determination as to whether the City needs to have 36 employees receiving over $200,000 each in cash compensation.

Pension funding is also within the city’s control. Some California cities have made additional CalPERS contributions to reduce their unfunded liabilities. For example, Brentwood made $22 million in pension contributions above and beyond those required by CalPERS between 2018 and 2024.

Similarly, Petaluma could also prefund its retiree health benefits, a practice followed by Corte Madera in nearby Marin County. In 2024, Corte Madera had $7.3 million in Other Post-employment Benefit (OPEB) obligations and $5.3 million of assets earmarked to pay these benefits. Other Bay Area cities, such as Walnut Creek, do not even offer retiree healthcare benefits at all.

The fact that Petaluma makes the CalPERS’ minimum retiree healthcare benefit payment does not mean that it is offering a “defined contribution” plan as the city asserts; in fact, the minimum benefit increases each year with medical cost inflation. None of this excuses the city’s failure to prefund retiree healthcare benefits. While city employees are working, they are earning retiree health benefits. Intergenerational equity requires that the city pays these benefits as they are earned and not leave them to future taxpayers.

Petaluma’s Credit Rating

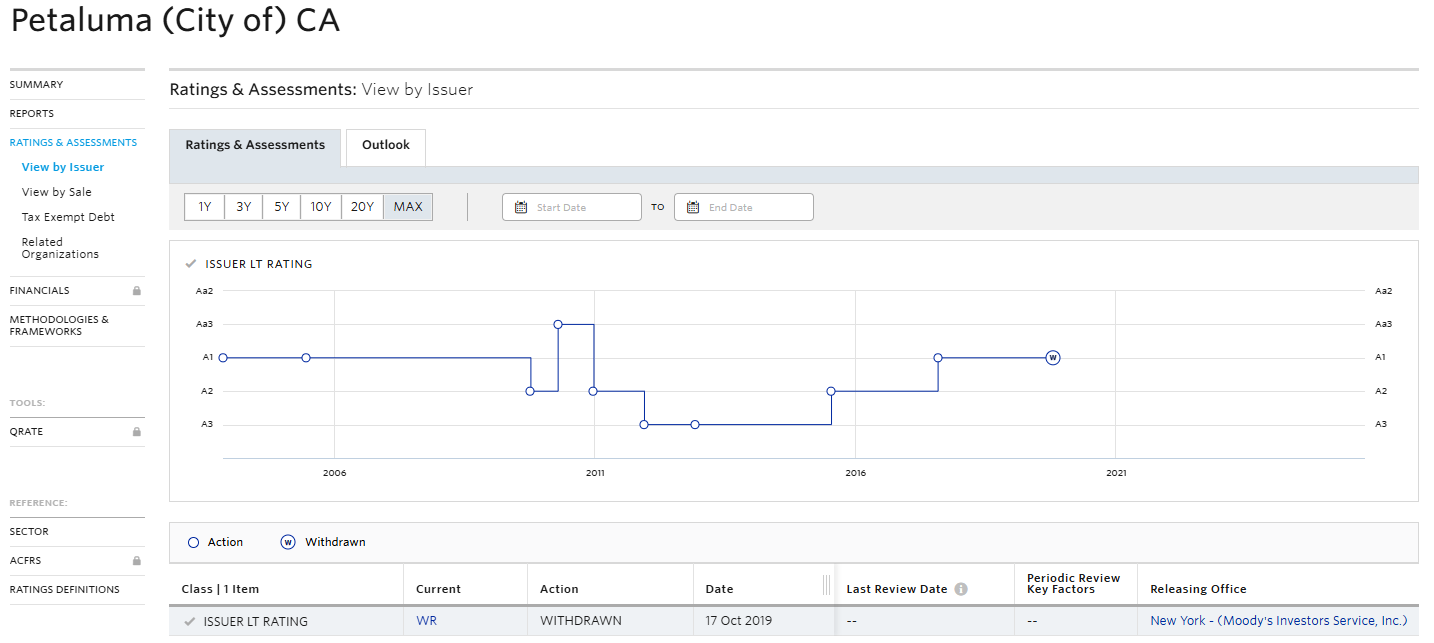

We also note that the City of Petaluma reports receiving a credit rating of AA from Moody’s Investors Service. But we cannot independently verify this assertion and would welcome more information from the city. While we’re waiting, we’ll note that “AA” is not a valid Moody’s rating. Moody’s assigns many cites ratings of “Aa1,” “Aa2” or “Aa3,” but the symbol “AA” is not in the agency’s list of symbols.

It’s more critical to point out that Moody’s website shows that it withdrew Petaluma’s bond rating in 2019. At the time of that withdrawal, the Moody’s rating was A1 which is below any of its “Aa” ratings. Registered Moody’s users can see Petaluma’s credit rating history in the accompanying screenshot.

What can local officials do to course correct if their city is fiscally off track?

The dashboard provides key financial metrics to help local elected officials, analysts, reporters and citizens understand how cities are performing overall and in comparison to other cities, and spotlight concerning financial trends. Tracking local financial metrics, such as liabilities and revenue trends, is crucial. Many cities have potentially catastrophic unfunded retirement liabilities. Other municipalities are consistently late in submitting their annual audits, which means officials are making budget decisions based on incomplete, missing or outdated financial reports. For FY 2024, dozens of cities have yet to submit their ACFRs.

CPC municipal finance experts are available to consult confidentially and at no charge with local governments to help them better understand their fiscal health score and ways they could strengthen their fiscal health. CPC has also published a Municipal Finance Triage Guide to help local elected officials evaluate what they can do to improve their budget forecasting, planning and management, and help at-risk cities proactively address foreseeable challenges.

###