In the last few months, I’ve gotten into the habit of picking up my daughter from her crib after she wakes up in the morning and carrying her to our dining room. Before heading into the kitchen to make her a bottle of formula, we stand in front of a built-in cabinet, of which the middle shelf is filled with an assortment of family photos, including several of my late father.

“Buenos días, abuelito!” I say with a wave, a motion she recently started emulating.

You’re reading Latinx Files

Fidel Martinez delves into the latest stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

By continuing, you agree to our Terms of Service and our Privacy Policy.

I don’t care that her hand movement is nothing more than part of her development — that her brain is learning to associate gestures with speech — or that she hasn’t any sense of who he was and what he means to me. The fact that she’s just an 8-month-old baby doesn’t stop me from believing that she is consciously greeting her grandfather, who died 11 months before she was born.

In a perfect world, their lives would have overlapped. He would be here to dote on her much like he did with his other grandchildren. He’d bounce her on his lap and make her laugh.

But life is far from ideal. To borrow my old man’s favorite tautophrase: It is what it is.

It’s on me to ensure my daughter develops a relationship with him in his absence. And so, every morning, she and I partake in this little ritual in hopes that it becomes part of her morning routine, much like brushing her teeth and washing her face will be.

It also doesn’t hurt that this little song and dance has done wonders in helping me process my grief from his loss.

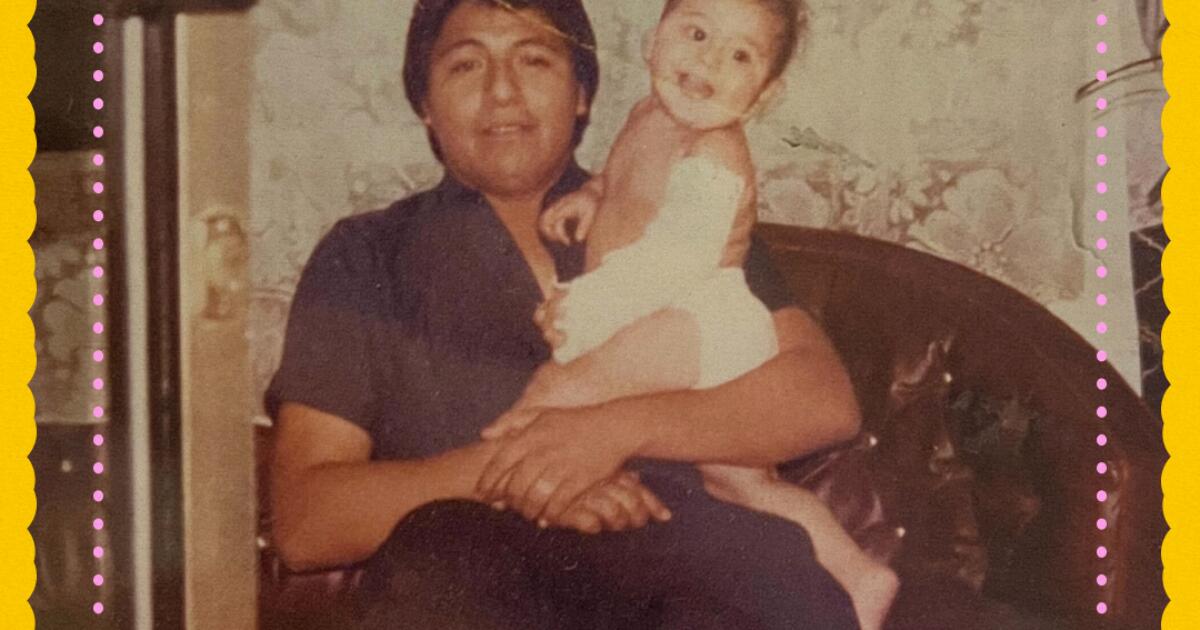

Of the photos on the shelf, my favorite is the one featured above, which shows Fidel Martinez Sr. in his early 20s and me as a baby in his arms. “Look, mija,” I say and point, trusting that she’s grasping the parallels I’m drawing between the image and me holding her at that moment, that she’s picking up on the generational continuity I’m highlighting.

I don’t think it’s going to be particularly hard for her to feel his presence in her life. His memory is embedded in physical objects found throughout our house. Many of these are items that belonged to him that I kept. There’s the sterling silver bracelet my mom gifted him one birthday after he sheepishly coaxed her into buying it for him, and that I now refuse to take off. There’s the Raul Jimenez jersey from his stint at Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C. hanging in my closet, a symbol of his affinity for Mexican athletes thriving abroad, and that now doubles as a source of motivation for me to lose the weight I’ve put on from grief so I can wear it.

Then there’s the stuffed pig — a nod to “Cochinitos Dormilones,” the famous Mexican children’s song he loved to sing to my siblings and me when we were kids — that my daughter sleeps with, made from the fabric of one of his favorite shirts. I’ll tell her these anecdotes and many more, because I want her to have a better understanding of who I come from.

I’ll be honest: I really struggled writing today’s newsletter — hence the tardiness of this week’s edition — because it’s quite indulgent to write about one’s own life, especially in a space dedicated to the broader Latinx experience. But we’re also in the midst of the Día de Muertos season. What better moment to talk about my dead dad than now?

Americans, for the most part, have difficulty talking about death, which feels silly because what’s more universal than dying? I think that’s why Día de Muertos — in addition to the Disneyfication of the holiday — has grown in popularity in recent years. It makes it OK to talk about a subject that’s so taboo, and it gives permission to people to explore their origin stories.

And if I’ve learned anything, it’s that humans are narrative creatures. Telling stories about who we are, where we come from, where we want to go and what it all means is in our nature. It’s how we make sense of the world and what gets us going.

My father will always be an essential part of the family, even in the afterlife. Just because he’s no longer alive, it doesn’t mean that he’s not a key part of my narrative. I’m hoping that in talking about him to her, he becomes the same for my daughter.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Contribute to our Día de Muertos digital altar and come celebrate the holiday with us!

In 2021, The Times published its first Día de Muertos digital altar. The project was born out of a desire to virtually replicate the communal experience found in the many holiday observances held across Southern California that were canceled that year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fifth iteration of the digital altar went live last week.

The tool lets readers make an ofrenda by uploading a photo of a loved one who has passed along with a short written message. These submissions are manually reviewed by a De Los staffer before they’re added to the community altar.

De Los will also be hosting its own celebration Saturday at Las Fotos Project in Boyle Heights. The event will feature a public altar, face painting, a paper marigold workshop by Self Help Graphics and a sugar skull decorating class hosted by Tía Chucha’s Centro Cultural and Bookstore. Admission is free, but will require an RSVP. To learn more and to sign up, you can go here.

Stories we read that we think you should read

Unless otherwise noted, stories below were published by the Los Angeles Times.

ImmigrationArts, entertainment and cultureMiscellanea