At the Greater Good Science Center, one of the online courses we offer is Mindfulness and Resilience to Stress at Work.

This course includes articles, videos, interactive surveys, and activities and exercises that learners can do to strengthen skills that enhance and sustain their happiness at work. Featured as “Learning by Doing” sections of the courses, these activities include things like engaging in a variety of self-reflection and mindfulness practices.

After completing each mindfulness activity, learners are asked to rate their own experience during the exercise in three ways: Did they feel distracted or focused? Tense or calm? Critical or friendly? Learner ratings give us insight into the potential impact of different exercises, activities, and practices on happiness and well-being at work.

Advertisement

X

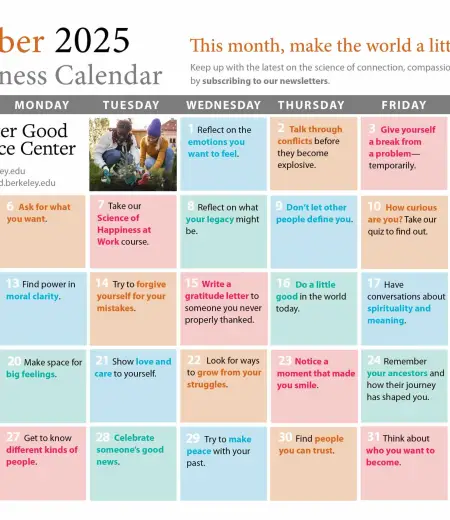

Keep Up with the GGSC Happiness Calendar

Make the world a little better this month

As someone who hopes to become a therapist, I’m especially drawn to mindfulness practices that help people pause, notice what they’re feeling, and reconnect with what is most important to them. So, I took a look at how learners felt while doing four brief audio-guided mindfulness practices in the Mindfulness and Resilience to Stress course. According to this data, even five-minute mindfulness practices can help people feel more focused, calm, and kind.

Four brief mindfulness practices

The first practice that learners are encouraged to try is called Interoceptive Mindfulness, a five-minute audio-guided exercise that resembles a body scan meditation. Led by Eve Ekman, a senior fellow at the Greater Good Science Center, the practice encourages listeners to gently focus on noticing sensations in the body in a nuanced and granular way. This kind of attention to sensation, what scientists call interoception, includes awareness of everything from changes in heartbeat and visceral tension to how emotions like anger, sadness, or joy feel in our muscles and tissues.

As Ekman explains, becoming more aware of these signals is like developing an “early warning system” for our emotions. Without awareness, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to regulate what we feel. By tuning into physical sensations, people can often find a measure of relief from spiraling thoughts and show up more present in stressful situations. For example, the practice encourages listeners to “inhale, paying close attention . . . to the sensations of breath as our belly rises through the inhale.”

In practice, this means that learners are invited to attend to sensations throughout their body as they are occurring in real time, focus on their breath, and let incidental thoughts arise and recede without judgment.

The second five-and-a-half-minute practice in the course is called Mindfulness of Thoughts. This practice shifts the focus from bodily sensations to the activity of the mind itself. In Ekman’s words, “our minds can sometimes be sharp and clear, and other times restless, jumping from one thought to the next like we’re just along for the ride.” Mindfulness of Thoughts is intended to help learners notice these patterns and gently build intention around their attention. For example, learners are prompted to “shift attention . . . opening up to notice the thoughts, memories, and images that pass by.”

As clarification, Ekman explains that mindfulness is not about “clearing the mind,” a common misconception, but about learning to return, over and over, to a chosen point of focus. That act of returning, the practice suggests, is what strengthens attention. By practicing this gentle noticing and redirection, learners begin developing what Ekman describes as “balanced attention,” a way of concentrating that isn’t rigid or self-critical, but refreshing and sustainable. Research finds that training attention in this way improves focus, helps people let go of distractions and distressing thoughts more quickly, and boosts both resilience to stress and performance at work.

The third nearly six-minute practice offered in the course is called Handshake with Stress. Unlike the previous ones that focus on inner sensations or the flow of thoughts, this practice invites participants to turn toward their emotions directly, particularly the difficult ones. As Ekman describes, this kind of awareness involves noticing what triggers unpleasant feelings, how they arise in the body, and how we typically respond. Developing this awareness allows us to bring more choice and clarity into our reactions.

In the audio, Ekman reminds learners that people feel the full range of emotions at work: joy, frustration, excitement, and overwhelm. Emotional awareness doesn’t mean trying to eliminate stress or suppress or avoid negative feelings; it’s about recognizing feelings and thoughts as they happen and learning to respond in ways that are more aligned with our values. The practice encourages listeners to “continue simply shaking hands with the felt sensations of stress in the body, noticing the sensations but not engaging with the memory or story.”

The fourth and final practice in the course, also just under six minutes long, is Loving-Kindness Meditation. This practice shifts from focusing on stress toward cultivating positive, prosocial feelings; it is designed to generate warmth and goodwill, both for ourselves and for others, using memory and imagination. For example, the audio invites learners to “shift into this practice of joy, by bringing to mind someone who we really believe has our best interests at heart . . . imagine them truly wishing for you to be happy.” Unlike concentration practices that train attention, Loving-Kindness Meditation strengthens our capacity for compassion, care, and shared joy—even in the face of challenges at work.

In the audio, Ekman highlights the broader scientific foundation for these methods. Compassion and loving-kindness are not new ideas, but contemporary science finds that they can enhance resilience, emotional flexibility, and collaboration. By visualizing a colleague or family member, and sending a genuine wish for enhancing their happiness and well-being, we train our minds to respond to difficulties with kindness rather than stress or self-criticism.

The Loving-Kindness Meditation practice often unfolds in two steps: first, envisioning a loved one, colleague, or client and wishing that they flourish; second, extending the same sentiment toward ourselves. This shift in perspective naturally evokes positive emotions, reinforcing a sense of connection and common humanity. Research finds that loving-kindness meditation increases access to positive states, broadens outlook, and makes us more open to opportunities in work and life.

The power of short practices

Immediately after completing each type of mindfulness practice offered in the course, approximately 4,000 learners posted ratings of their experience across three dimensions: how distracted vs. focused, tense vs. calm, and critical vs. friendly they felt while they were doing the practice.

Self-rating scale used in the course. After each practice, learners rated themselves on three dimensions: 1 = distracted to 5 = focused, 1 = tense to 5 = calm, and 1 = critical to 5 = friendly.

When I analyzed these responses, I found clear, consistent patterns:

Distracted vs. focused: Learners’ ratings shifted toward greater focus over time, from an average of 3.38 after the first one, Interoceptive Mindfulness, to 3.71 after the fourth, Loving-Kindness Meditation. This suggests that even very brief mindfulness practices can cumulatively build attentional stability.

Tense vs. calm: Average ratings also veered toward calm over time, from 3.27 at the beginning (after Interoceptive Mindfulness) to 3.63 by the end (after Loving-Kindness). There was, however, a dip in this pattern when learners did the Handshake with Stress practice. Importantly, this isn’t a “failure” of the practice; it actually reflects its purpose. Learners were invited to sit with something stressful, which would make anyone feel less calm. This finding indicates that the pattern in our data is not random; it reflects what we would expect given the nature of the practice.

Critical vs. friendly: Ratings of friendliness increased the most from the first to the fourth mindfulness practice in the course, from 3.34 to 3.92. Again, this pattern flattened after the Handshake with Stress practice, followed by the largest increase for Loving-Kindness. The flattening of friendliness after Handshake with Stress is consistent with existing evidence suggesting stress can make us less kind. Nevertheless, the final Loving-Kindness practice in the course seemed to leave people feeling especially warm and open.

Average self-ratings across four mindfulness practices (Interoceptive Mindfulness, Mindfulness of Thoughts, Handshake with Stress, Loving-Kindness) on three dimensions: focus, calmness, and friendliness.

Why it matters for work and well-being

These results suggest that brief, varied mindfulness practices can gradually help people feel more focused, calm, and friendly, even in the midst of a busy workday. They also highlight the value of variety: While some practices (like Handshake with Stress) feel less soothing in the moment, they may serve an important role in resilience by encouraging people to face difficulty rather than avoid it.

However, this analysis can’t clearly distinguish differences in people’s experiences across the four mindfulness practices. For example, while ratings for friendliness were highest for Loving-Kindness, this was also the last practice, so the increase could reflect cumulative effects over time rather than being specific to that practice. Interestingly, ratings for focus did not decrease during the Handshake with Stress practice, suggesting that even challenging exercises don’t necessarily undermine attention.

For me, this analysis underscored how much room there is for incremental improvement in workplace well-being. It also reinforced the importance of making practices approachable; just five minutes can be enough to make a difference. If you’re curious, you can try these practices yourself in the Mindfulness and Resilience to Stress at Work course on edX. Even a few minutes a day may help you feel a little more focused, calm, and friendly, at work and beyond.