The future of the I-980 highway won’t arrive without a reckoning with the harms inflicted on West Oakland’s Black community when it was built.

That was the message from the Black old-schoolers from West Oakland who showed up at what was dubbed an I-980 Block Party on Saturday. They came to participate in the Vision 980, an effort by Caltrans, the state transit agency, to reimagine the freeway by either capping it, removing it, or doing some safety upgrades but leaving it as is.

Hosted by Evoak!, an Oakland nonprofit dedicated to advancing equity and sustainability, the event took place on a rainy Saturday afternoon at Preservation Park, the stately, landscaped neighborhood created from the relocated Victorian homes of Black residents displaced by the highway between the 1960s and the 1980s.

Randolph Belle, whom Caltrans contracted to run Vision 980’s community-building and outreach, worked for months with local colleges, community groups, and survivors of the displacement to put the event together. Together they created interactive stations where people could learn about the history of the I-980’s construction, including how it led to the loss of housing for some 500 Black families. The highway dates back to the years after World War II, when President Dwight Eisenhower launched a nationwide program to build highways, often through taking possession of the properties of low-income communities of color through eminent domain. That undertaking devastated West Oakland, where the majority of the households were Black.

“The plans that have come before this were really talking about freeway fighting, decreasing vehicle miles, travel, environment, and open space,” Belle said to a small group gathered under a tent canopy to avoid the rain. “We’re talking about first prioritizing harm repair for the legacy residents of West Oakland.”

A banner for the Vision 980 event at Preservation Park in Oakland highlighted Black residents whose families were negatively affected by the construction of the highway. Credit Jose Fermoso

A banner for the Vision 980 event at Preservation Park in Oakland highlighted Black residents whose families were negatively affected by the construction of the highway. Credit Jose Fermoso

For one station, students from the California College of the Arts designed three potential freeway outcomes Caltrans has proposed in a sandbox that was bisected to help people better understand what they would look like in three dimensions, for example, how capping the freeway would leave the trenched highway intact for drivers.

Another station featured a board game whose play pieces were cards featuring different types of residents — students, working professionals, retired folks — inviting players to consider their neighbors’ needs as they moved through a redesigned neighborhood.

At history stations, participants could listen to recordings of interviews with older Black residents of West Oakland speaking about their lives before the freeway, some of whom recalled playing in the streets with their friends and leaving their homes’ doors unlocked because it was such a safe, communal neighborhood.

At a block print area, participants could paint wooden cutouts created from the negative space surrounding photos of West Oakland residents and then make prints on large paper architect plans of the original neighborhood.

“My team learned a lot about the legacy residents, the removal because of racism,” said Zi Ooiziooi, one of the CCCA students. “We also found out people don’t even use this freeway a lot, so by removing it, it could give back legacy residents reparations and make this community better.”

A station at the event let people create images combining vintage maps with block-painted images of homes lost during the I-980 construction displacement. One participant said, “Seeing what used to exist in those spaces before prevents the memory from being erased.” Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

A station at the event let people create images combining vintage maps with block-painted images of homes lost during the I-980 construction displacement. One participant said, “Seeing what used to exist in those spaces before prevents the memory from being erased.” Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

Another CCCA student, Ritika Menon, shared that she was surprised to learn about the lack of resources in West Oakland, including the scarcity of grocery stores due to disinvestment. She helped design a vinyl map of West Oakland that was spread out on the concrete so people could walk around on it, exploring the area’s most significant needs and most dangerous roads.

Several participants told The Oaklandside they appreciated the organizers’ efforts to simplify a complicated topic. But many more felt compelled to tell the elders on hand that they enjoyed their stories.

Celia K. Edwards, who identifies as an Afrofuturist, sat quietly, listening as the elders spoke at the history storytelling table, occasionally scribbling notes. She told us that, as an Oakland transplant, she felt she’d received a degree in the trials and tribulations of the neighborhood, as well as the role of banking in community harm, from the demise of the Freedman’s Bank to the history of redlining, which led to generational distrust in financing for African Americans.

“The depth and breadth of it is disgusting,” she said. “It was amazing to have legacy residents share their knowledge and wisdom. In order to achieve the outcomes you want, you’re much better off understanding the big picture.”

A right to housing for displaced families

Organizers and residents passionately discussed the options for reimaging or simply improving the I-980 highway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

Organizers and residents passionately discussed the options for reimaging or simply improving the I-980 highway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

The daylong event sparked impromptu conversations about the freeway’s impact.

One of the most passionate of those took place two hours in, around a miniature wooden reproduction of West Oakland, where participants were invited to add buildings made of Legos along the freeway’s current path.

As Belle joined in to discuss the three proposed options for the I-980, two West Oakland advocates, Anisha Rasheed and Cathy Leonard, interjected with some historical context. They noted the freeway was designed to allow people to bypass Oakland to get to San Francisco. The I-980, as historians have documented, was planned as an entry point onto a second Bay Bridge that never materialized.

“The I-980 was made to serve suburbanites, and look at all the homes and businesses from the Black community that had to pay for that,” Rasheed, an administrator for the Oakland Unified School District and an assistant vice principal at Montera Elementary school, said, gesturing at the wooden model. “For people who don’t even live in Oakland, don’t pay taxes in Oakland, don’t pay taxes in our county, right?”

A few participants raised an urgent concern about the scenario in which the I-980 is removed to allow construction of new housing: the potential for a new round of displacement.

Rasheed noted that no efforts are underway to remove freeways in whiter, wealthier areas of Oakland, such as Highway 13, which connects the Oakland hills to the cities of Berkeley and Piedmont.

Paul Cobb, the former Oakland Post publisher, whose family alongside others unsuccessfully fought to prevent a dozen blocks in West Oakland from being bulldozed to build a new U.S. Post Office processing facility, brought up previous agreements with state and county agencies as examples of how the community could be fairly compensated during the redevelopment of formerly Black neighborhoods that were redlined. For example, in Berkeley, Belle and his group recently pushed for a benefit agreement with the city that led to funds for affordable housing.

Some of Cobb’s advocacy decades earlier, in collaboration with the Black Panthers, forced California Governor Jerry Brown in the 1970s to increase job opportunities for Black West Oakland residents during the construction of the I-980. He said at the event Saturday that concrete and carpentry business run by Black people also benefitted.

“So it can happen if we organize, demand, and push,” he said.

Residents added Lego pieces to a miniature map to envision what high-rises might look like between West Oakland and downtown, in place of the freeway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

Residents added Lego pieces to a miniature map to envision what high-rises might look like between West Oakland and downtown, in place of the freeway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

Cobb said it wasn’t too late to insist that the original West Oakland residents and their descendents get some sort of agreement if housing is built on top of the I-980’s path that could make them whole after the financial harm they suffered over decades is quantified. He said they should qualify for an apartment or home in any future housing development there if they could trace their lineage to the original I-980 displacement.

“ If this becomes a multi-billion dollar development, that it is almost like an inheritance,” Cobb said.

“Boom,” Belle replied.

“If there’s going to be a community benefit agreement, it has to be the best and biggest one ever done,” Belle said. “If there’s gonna be a preference program, it has gotta be the most inclusive and all encompassing that has ever happened in the country.”

Even a community benefits agreement that offered former residents priority housing, several participants said, wouldn’t lessen their concerns about the negative generational impacts of gentrifying forms of development.

Patricia Scott, the former executive director of San Francisco’s Booker T. Washington Community Service Center, which services Black families and youth, told The Oaklandside over lunch that redevelopment in San Francisco has “run out” Black people from the city.

“So you have to be very careful,” she said. “The racism is so prevalent, even with white liberals.”

“We live inside of a system, in the United States of America, that keeps working, it keeps planning, it keeps moving forward,” Rasheed, the school administrator, told The Oaklandside. “A pig squeals on the way to the slaughterhouse. We want to know why, how, what for, who benefits? How is this gonna make my grandchildren’s life better here in this city? Or are they going to be destined to have to leave the Bay Area in order to have a decent job, marry, raise their own kids? And is there really the will to restore community — that this isn’t just about developers building some damn apartment buildings? That’s not community.”

Imagining how life could have been different

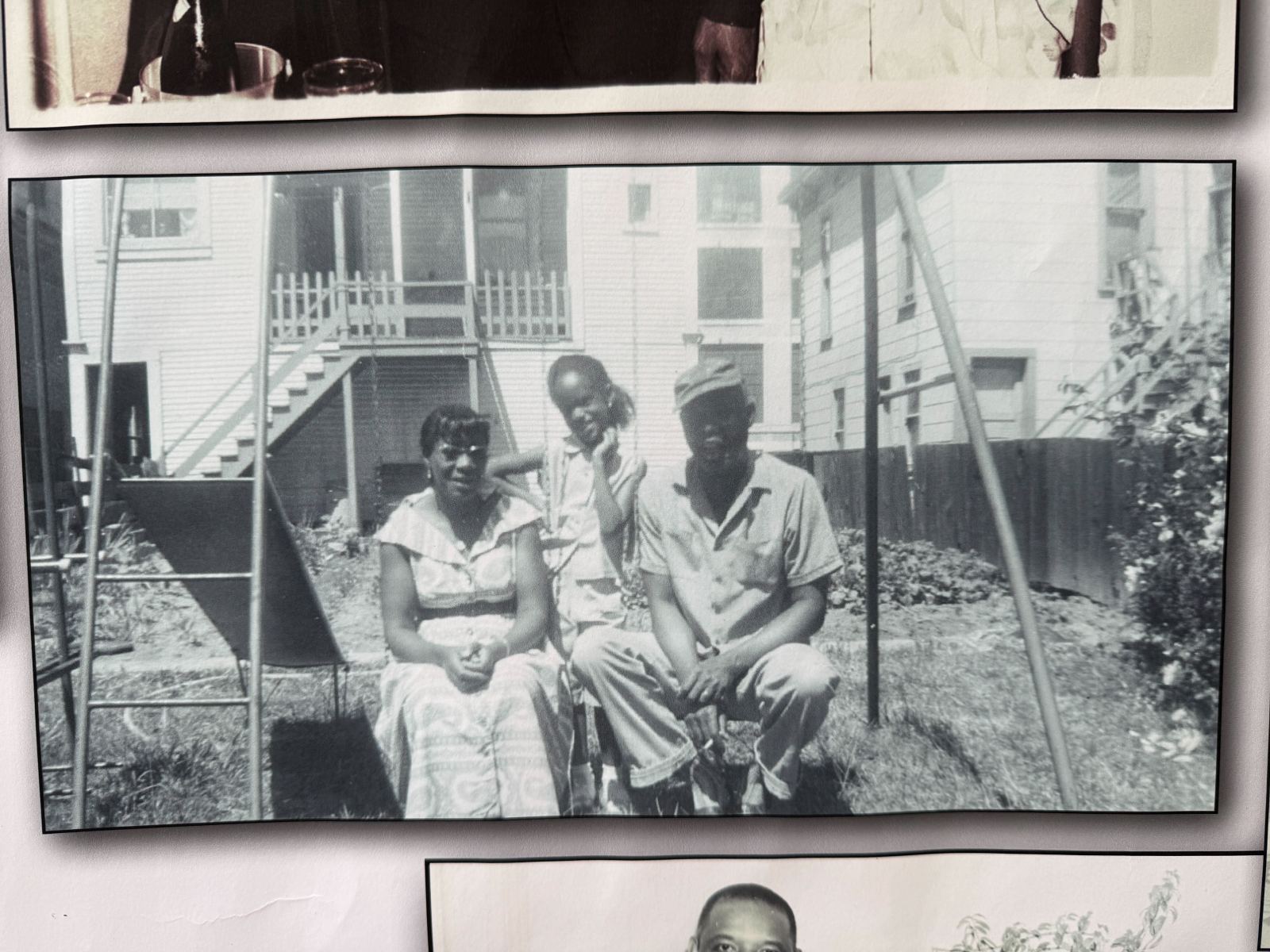

An exhibition of West Oaklander Ernestine Nettles’ photographs showed the family’s backyard in the years before the freeway was built. Credit: Jose Fermoso

An exhibition of West Oaklander Ernestine Nettles’ photographs showed the family’s backyard in the years before the freeway was built. Credit: Jose Fermoso

As The Oaklandside has previously reported, the idea to bring down the highway came out of a national movement to “reconnect” previous Black, brown, and Asian neighborhoods to parts of cities and economic opportunities after freeways had cut them off.

Yet in Oakland, the people who first raised the idea of taking down the I-980 to reconnect West Oakland to downtown and building housing were a couple of developers, including a former member of the Oakland Planning Commission, Jonathan Fearn.

“Make it make sense why you wanna do this,” a longtime West Oakland resident named Melody Davis said, holding forth to several young residents. “Make it make some common sense. Keep it like it is. Do something for the children that are hurting here in West Oakland, instead.”

She said many people she’s spoken with in West Oakland do not support tearing the I-980 down. She said she will oppose it, just like she opposed John Fisher’s baseball stadium, which would have cost billions of dollars.

“It’s unacceptable to me, and I’m gonna holler and I’m gonna scream and I’m gonna get somebody to help me,” she said.

West Oakland legacy resident Melody Davis said she opposed the teardown of the freeway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

West Oakland legacy resident Melody Davis said she opposed the teardown of the freeway. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside

The most sobering story related to the I-980’s legacy of displacement came from Cobb.

Pulling up his Oakland Larks baseball cap so people could see his face, he said that a few years ago, when he was out with members of his church in West Oakland to feed the unhoused, he ran into someone he recognized. He asked the man whether he was related to an old friend, someone he’d worked with in those long-ago fights against harmful development. It turns out he was his friend’s son, living on the same streets where his father had fought against displacement and government-led injustices. And he was not the only unhoused person with that background, Cobb said. The implication was that that man’s condition viscerally represented the injustices and lack of financial support for the community – indeed, the robbery of Black families’ potential earned capital through the region’s growing property values – by the city and state, and that they couldn’t afford to let that happen again with the I-980 project.

“The irony is, you know those portable houses right next to 27th Street, what they call Northgate?” Cobb said. “He was living there. And his family was a part of the movement with us, that helped fight for that neighborhood. And he didn’t know that.”

“*” indicates required fields