Supporters of the vast, but thus far elusive, potential of nuclear fusion have released a “road map” that quantifies the economic impact the nascent industry could deliver for California — provided state policymakers make regulatory and legislative changes, plus financial incentives.

“With the right support, California can lead in the commercialization of fusion energy, capturing the economic benefits that come from it while reshaping the global energy landscape,” said Eduardo Velasquez, a senior director at the San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation, and author of the road map. The interactive web report predicts fusion has the potential to support more than 40,000 jobs and inject as much as $125 billion into California’s economy in the next decade.

The road map describes California as a global leader in fusion and lists San Diego as one of the state’s regional clusters, given the amount of research and development done over the years at General Atomics and UC San Diego.

The report was underwritten by General Atomics, with research contributions by Boston Consulting Group.

“Fusion is having its Silicon Valley moment,” Mike Campbell, mechanical and aerospace engineering professor at UC San Diego, said. “What happens in the next three to five years will decide whether California owns the industry or watches it leave.”

But nuclear fusion has its share of critics and Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists, cast a skeptical eye on the road map’s projections.

“I don’t put much stock in what that report says,” Lyman said, since General Atomics funded it. “I think it’s pretty clear that the enthusiasm that appears to be increasing for commercial nuclear fusion is far ahead of what the technology can actually feasibly deliver in the foreseeable future.”

What is fusion?

Nuclear fusion differs from nuclear fission, which is the process used in nuclear power plants such as the now-shuttered San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station.

Fission splits the nuclei of atoms to create power while fusion causes hydrogen nuclei to collide and fuse into helium atoms that release incredible amounts of energy — essentially replicating the power of the sun.

To fuse hydrogen atoms on earth, they need to be heated to temperatures in the millions of degrees and produce a hot gas called plasma.

In theory, fusion applied to a commercial power plant could generate an almost infinite supply of carbon-free electricity without producing long-lived nuclear waste or running the risk of a meltdown. That’s why the prospect of a technological breakthrough with fusion has been called energy’s Holy Grail.

General Atomics has been a major contributor to fusion research for decades. Among its work, GA operates the DIII-D National Fusion Facility on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The company also fabricated and shipped modules forming a colossal magnet that make up a crucial portion of the ITER facility in France — an ambitious international fusion project.

Up in Northern California, scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory made headlines in late 2022 when 192 high-powered lasers created “net energy” through a nuclear fusion reaction. It marked the first time that a fusion experiment resulted in a greater amount of energy coming out than the amount put in. General Atomics assisted in the Livermore experiment.

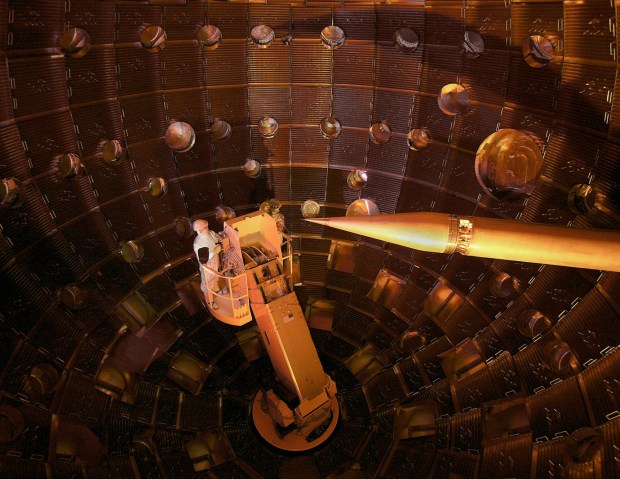

The interior of the target chamber inside the National Ignition Facility on the campus of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. (Lawrence Livermore National Lab)

The interior of the target chamber inside the National Ignition Facility on the campus of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. (Lawrence Livermore National Lab)

Privately funded fusion ventures have launched around the world, with billionaires Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Sam Altman among those investing in various projects. According to the Fusion Industry Association, global investment has surpassed $9.7 billion, with $2.6 billion raised in the past year alone.

What the road map is looking for

The San Diego Regional EDC road map says 16 core fusion companies are located in California — more than one-third of the U.S. total — and have captured some $2.2 billion in private and public funding.

The Golden State already accounts for about 4,700 jobs across California and generates $1.4 billion in annual economic output. But those figures can grow about 10 times more, “depending on successful commercialization and state policy decisions,” the report says.

Among its specifics, the road map calls for California to formally define nuclear fusion as a clean energy source.

“Other states in the country already do that,” said Alberto Fragoso, research manager with the San Diego EDC, who helped co-author the study.

Such a designation “would help provide relief” from the often lengthy reviews from California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), Fragoso said, for potential pilot programs and commercial research centers.

“It’s sort of the first step to unlocking everything that comes afterwards,” he said.

The report mentioned regions such as Kern County as locations where parcels of land could be bought at a reasonable price, compared other areas of California where real estate is very expensive.

The road map also called for “investment incentives” from the private sector, but mentioned that in “the early stages, substantial capital will be needed to scale and construct reactors, with public funding expected to play a leading role.” That would mean taxpayer dollars, but the report did not give a specific amount.

Some of the aforementioned $2.2 billion of venture capital raised by private firms investing in fusion comes from money supplied by the U.S. Department of Energy, or DOE.

“So rather than saying, ‘We need California to invest X amount of money,’” Fragoso said, “we’re just asking them to match the funds that are coming from DOE … we don’t have a specific number.”

The road map mentioned that a company based in Massachusetts called Commonwealth Fusion recently chose to develop its inaugural pilot plant in Virginia rather than the Bay State because Virginia offered a host of enticements that included “millions of dollars” in state and local funding incentives.

“Without decisive action, California risks losing fusion companies to other states offering more favorable commercialization conditions,” the report said.

Is it worth it?

Despite its vast potential, fusion has its share of detractors.

Nuclear fusion technology developed the hydrogen bomb in the 1950s but as an energy source, fusion power has been generated only for very short periods in the laboratory and no commercial reactors exist. There’s a long-running joke in the energy industry that commercial fusion is always 30 years away.

Daniel Jassby spent 25 years working with fusion and was a principal research physicist at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab. When asked in 2022 by the the Union-Tribune when a commercial fusion power plant might become a reality, Jassby said, “Not in this century; maybe in a hundred years.”

Lyman at the Union of Concerned Scientists is opposed to the road map’s call for public funding.

“Let the venture capitalists, who are high-risk takers, fund this effort. Don’t expose the public and taxpayer money to what could be a huge financial disaster,” he said.

Lyman also worries that money spent of fusion could siphon dollars from renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

“The world can’t wait for these science projects to work themselves out over many decades,” he said. “The emphasis really needs to be on the technologies that have been proven already.”

But U.S. Rep. Scott Peters, D-San Diego, came out in favor of the road map.

He pointed to predictions that energy demand in the U.S. will rise 15% or more in the next decade due to factors that include the growth of artificial intelligence, putting more upward pressure on already-high electric bills in California. Perhaps a fusion breakthrough can be the answer.

“I would say the interest of taxpayers is in cheap energy, so this is a means to get them what they want,” Peters said. “I’m not sure if you told them they want fusion they’d understand right off the bat, but this is how we conquer the energy problem and I think taxpayers want us to do that.”

State senator Catherine Blakespear, D-Encinitas, and chair of the Environmental Quality Committee in Sacramento, also voiced her support.

“We need to have a clean energy future and fusion seems like it could (not only) provide the clean part but also the abundant part,” she said. “The promise of fusion is important and I feel like we need to make that commitment real. So having California provide the necessary background for it to take off here instead of another state is a good idea.”

At a time when Democrats and Republicans seem to battle nonstop, fusion appears to be one of the few areas of bipartisan consensus.

Just one week after the San Diego Regional EDC report came out, the U.S. Department of Energy under the Trump administration released its own Fusion Science and Technology Roadmap on Oct. 16.

The 52-page report was touted as a national strategy to align DOE, the industry and national laboratories in the hopes of delivering commercial fusion energy to the grid by the mid-2030s.

But similar to the San Diego EDC report, the national road map “is not committing DOE to specific funding levels, and future funding will be subject to congressional appropriations.”

Isn’t there ban on nuclear in California?

In the mid-1970s, California passed a law placing a moratorium on building any new nuclear power plants in the state until the federal government comes up with a nuclear waste disposal plan, including the operation of a permanent site to store spent fuel from commercial plants.

With work on the Yucca Mountain repository halted during the Obama administration, the federal government has yet to find a location.

However, the law says “no nuclear fission thermal power plant” can be built until those federal requirements are met. It makes no mention of nuclear fusion.

Given that distinction, Fragoso of the San Diego Regional EDC said, “this enables fusion to go on a different pathway than the one that’s currently in place for fission.”

With the ongoing dismantlement of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, the only remaining nuclear fission facility still generating electricity in California is the Diablo Canyon Power Plant near San Luis Obispo.