Sign up below to get Mission Local’s free newsletter, a daily digest of news you won’t find elsewhere.

Lording a nearly mile-long stretch of coastline along the city’s southeast edge is a massive gantry crane. It’s taller than the Statue of Liberty, and as heavy as the Eiffel Tower. This steel behemoth once swapped out gun turrets on battleships in the 1950s and ‘60s when the neighborhood was a hub of industry and military might.

But for nearly 30 years, the Navy hasn’t been fixing ships here — they’ve been fixing the mess left behind after shipyard operations stopped in the wake of the Cold War.

That cleanup hasn’t gone without its share of setbacks. On Wednesday, the San Francisco Department of Public Health found that the U.S. Navy measured levels of airborne plutonium twice the recommended levels in November 2024 on a parcel of the shipyard.

Want the latest on the Mission and San Francisco? Sign up for our free daily newsletter below.

San Francisco officials say they were kept in the dark — the Navy didn’t tell them until October this year, 11 months after the radioactive element was found in the air.

Explore the Hunters Point Shipyard

Visualization by Vincent Woo. If you’re having trouble loading the model on this page, you can try viewing it directly.

Still, representatives from the Navy say that the shipyard will soon enter the final stages of its cleanup, which has left it largely unoccupied for nearly three decades.

The shipyard, they told residents in July, has reached radiation levels that are negligible.

When the cleanup ends, so will a century and a half of the navy’s presence in Bayview-Hunters Point. If everything goes as planned, the mile-long Naval shipyard could be handed back to the city as soon as 2036.

Mission Local has put all the significant events in that history onto a timeline. We divided the story into four sections chronicling the shipyard’s long history.

Early history

Superfund site

Tetra Tech

Sea level rise

From fishing spot to industrial hub

1867

The California Dry Dock Company opens Hunters Point Dry Docks on about 30 acres of coastline in

the Bayview — a large quantity of serpentine rock in the area makes it ideal to stabilize large

structures. Before this, the area was a productive fishery used by the Ramaytush Ohlone, among

others. Chinese-owned shrimp fisheries remained nearby until the late 1930s.

Ramaytush Ohlone in a tule boat in the San Francisco Bay, 1816. Painting by Louis Choris. Courtesy of UC Berkeley Library.

1870

The Union Iron

Works Company acquires the site and builds 1,000 foot-long drydocks — large enough to

build or repair the biggest commercial and military ships of the era.

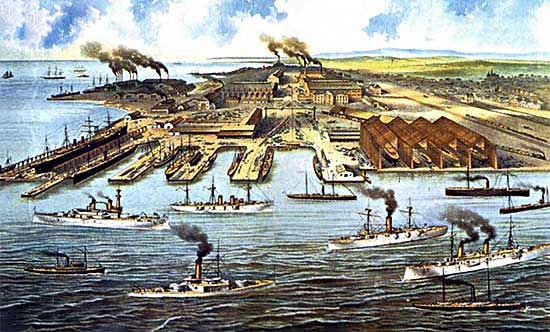

Union Iron Works at Pier 70. Painting Courtesy of Maritime Museum Library.

1905

Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation acquires Union Iron Works.

Hunters Point Drydocks, pictured in 1910. Courtesy of National Archives of San Francisco.

1939 – 1946

The Navy purchases the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard and turns it into a hub for shipbuilding and

repair. By the end of World War II, the site has grown to nearly one thousand acres — almost

five miles of berths, seventeen miles of railroad track, 200 buildings and six dry docks. Nearly

one-third of the shipyard’s workforce are Black — many of them drawn here as part of the Great

Migration. In 2025, Bayview is still 23 percent Black, making it the only historically Black

neighborhood left in San Francisco.

Hunters Point shipyard manufacturing floor, pictured in June 1955. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy.

July 15, 1945

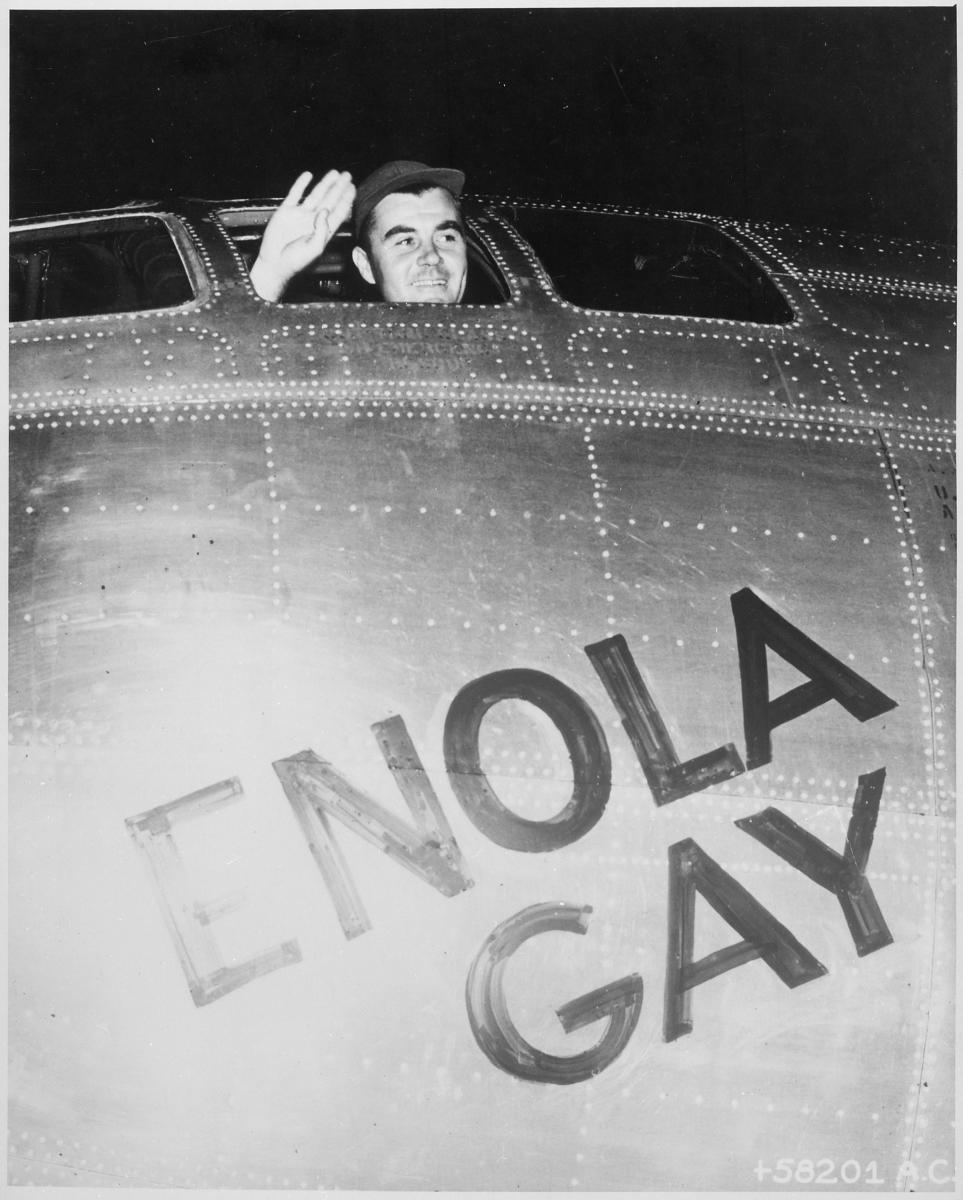

The components for Little Boy, the atomic bomb that the United States will detonate over

Hiroshima Aug. 6, 1945 is loaded onto the USS Indianapolis at Hunters Point to be delivered to

Tinian Naval Base. There, it is put onto the Enola Gay bomber.

Enola Gay, a bomber pictured in 1945, was used to drop “Little Boy,” an atomic bomb the components for which were manufactured at the Hunters Point shipyard. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

1946

WWII is over, and the Cold War has begun. Boat-building and maintenance work in the shipyard

dwindles. The top-secret U.S. Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) is established on the

site to study methods for protecting people and equipment after exposure to radiation.

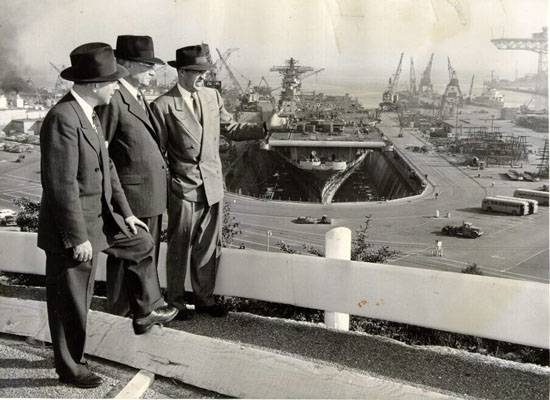

Navy Day, pictured at the Hunters Point shipyard in 1947. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy.

Birth of a Superfund site

1946

The Navy brings ships contaminated by radiation from “Operation Crossroads” and “Operation Redwing” — United States nuclear weapon tests — to the

shipyard. The Navy attempts to decontaminate them by hosing the ships off, sandblasting

their hulls and burning off 610,000 gallons of fuel oil that was rendered radioactive by the

nuclear testing.

A worker sandblasts a ship’s hull, date unknown. Photo courtesy of National Archives, San Bruno.

1947

The giant

gantry crane — then the largest in the world — is completed and becomes a key part of

Cold War weapons tests.

The giant gantry crane is pictured behind a sign advertising the building of the crane on Navy Day, 1946. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy.

1955

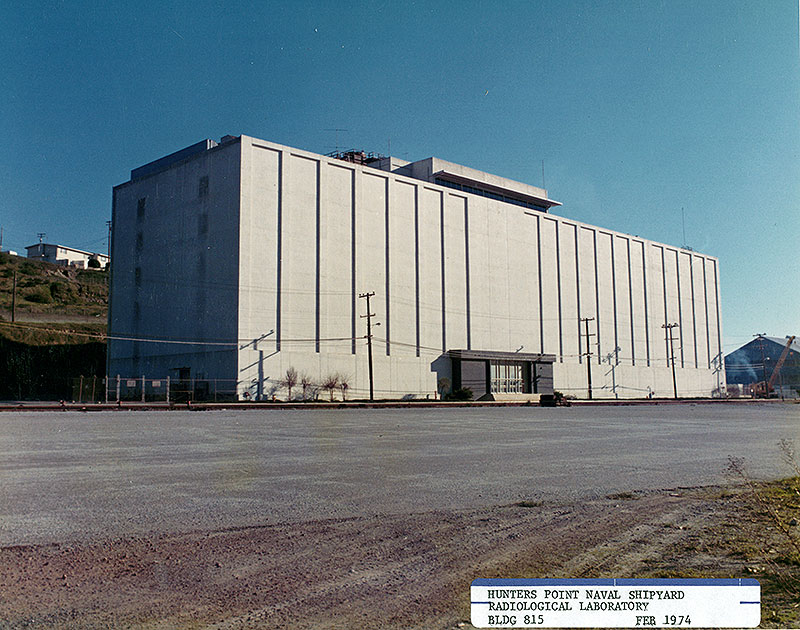

The Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory completes Building 815 — a six-story, windowless building within the shipyard to develop and test

defenses against radiation. It’s one of several sites the Navy uses as a base for radiological research

on human subjects.

Building 815, the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory’s headquarters, pictured in February, 1974. The building, which is located in Parcel A, has since been turned over to the city. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy.

A U.S. Navy researcher recruits members of the San Francisco 49ers football team to participate in a science experiment at the U.S.

Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory. While there is no proof the tests were carried out,

correspondence shows scientists planned to give some players injections of radioactive chromium,

as well as radioactive water to drink.

1956

A report from the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory states that

Hunters Point is the only facility on the West Coast authorized to dispose of radioactive waste.

That year alone, it adds, 980 tons of radioactive waste from a variety of sources were dumped

offshore — 19 barge loads, 2,913 drums filled with liquid and 53 concrete blocks containing

radioactive solids.

Men overlook the Hunters Point Shipyard, pictured in 1950. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

1963

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis the previous year, a treaty between the

United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union bans atmospheric nuclear testing.

1970s – ’80s

Neighborhood children like Arieann Harrison remember playing with friends in the vacant base

after it closed, entirely unaware of the toxic hazards that lay buried beneath the surface.

1980

As public pressure to do something about hazardous waste dumped by companies and government

agencies across the country, Congress passes the Comprehensive Environmental Response,

Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) which gives the EPA the authority to clean up hazardous

waste sites — or to investigate the source of the pollution and pressure whoever is responsible

to clean it up. Nearly everyone calls the program “Superfund.” Initially, cleanup of the average

Superfund site takes about four years, but as the years go on, that number begins to climb.

1988

The shipyard is placed in the federal Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Program, which is

intended to clean up and transfer military installations to public or private use.

1989

The EPA lists Hunters Point as a Superfund site The Navy is responsible for cleaning up the site

while the EPA oversees the process. Both agencies are responsible for paying for it.

1991

Parcels A, C and D begin cleanup operations.

1992

The Navy divides the shipyard into five parcels, from A to E, each with different clean-up

strategies. The parcels have been renamed and subdivided over the years, resulting in 15 total

areas in 2025.

The public is barred from each parcel until cleanup is completed and the land

is handed back to the city for redevelopment.

1995

Parcel E begins its cleanup. Parcel E was once a landfill. Its elevated methane levels are still under continuous monitoring in 2025. Federal and state regulators also declare that Parcel A is no longer a hazardous waste site. According to Navy documents, because it primarily housed administrative and residential buildings, cleanup was relatively simple and limited to things like removing asbestos and underground storage tanks.

1996

The Navy adds Parcel F — 446 acres of underwater land extending from the former base out into the bay.

Cleanup operations begin at Parcel B, the last onshore site to begin.

2004

Parcel A is handed back to the city for redevelopment.

2008

Parcel D is subdivided into two smaller “D” parcels: D-1 and D-2, a utility corridor UC-1 and Parcel G.

By 2027, every parcel besides the offshore Parcel F is expected to move into its final stage.

March 2026

The final phase for parcel D is expected to be completed.

Fall 2026

The final phase for Parcel C, excavation and subsequent groundwater treatment is set to complete after about a year of work. Monitoring of Parcel B also completes, after the area’s soil is replaced and paved over with “permanent cover” in 2025.

Summer 2027

One of the last cleanup efforts will commence in Parcel G: the demolition of potentially contaminated buildings is set to complete after 18 months of work. Cleanup is also set to begin at Parcel F, which is the underwater section of the site.

End of 2027

All of the remedies discussed in the fifth five-year report for parcels E and E-2 will be complete.

2036

The earliest year Parcel F cleanup may complete.

Tetra Tech Scandal

1989

The Navy contracts Tetra Tech, an engineering and environmental consulting firm, to test soil at

the shipyard and remove any that is contaminated. An exception is Parcel F, the underwater lot.

1999

The city awards rights to develop parcels A-1 and A-2 to housing developer

Lennar. Lennar pays nothing for the land but is responsible for all construction costs,

approximately $50 million. Under the agreement between the city and Lennar, when the units are

sold, the city Redevelopment Agency will receive 60 percent of the proceeds and Lennar 40

percent.

2005

Parcels A-1 and A-2 are officially handed off to Lennar, which begins development.

April 2014

An internal Tetra Tech report obtained by NBC Bay Area reveals that in 2012, the company caught employees trying to pass off dirt from a less polluted area of the base as coming from the site of Building 517, an area of Parcel E that had been used for radiation experiments. The discovery casts doubt on years of cleanup. The Navy’s internal investigation concludes that the Tetra Tech’s fraud took place 2008-2012.

2014-15

350 homes constructed by Lennar on former Parcels A-1 and A-2, go on the market, selling for $1 million apiece. By March 2015, they are all sold.

2015

Parcels D-2, UC-1 and UC-2 are transferred to the city.

2018

Letters between the Navy and the EPA reveal 97 percent of soil samples taken from Parcel G and 90 percent taken from Parcel B were handled by Tetra Tech and therefore cannot be verified.

The Navy claims because Tetra Tech had access to few soil samples from Parcel A, it does not need to be retested. According to Navy reports, Tetra Tech’s cleanup of Parcel A was completed before the alleged fraud took place.

May 1, 2018

Bonner & Bonner files a $27 billion class action lawsuit on behalf of Bayview residents against Tetra Tech in San Francisco Superior Court. The suit alleges that residents suffered health damages as a result of the botched cleanup effort.

May 2, 2018

Two Tetra Tech employees plead guilty to fraud amid clean-up efforts. They are sentenced to eight months in prison.

June 19, 2018

Homeowners on formerly Parcel A land allege that prior to buying, they were misled about the health risk associated with the area. The San Francisco Chronicle reports that the scans The California Department of Public Health plans to use to reassure homeowners cannot “detect two of the most harmful isotopes found at the Hunters Point Superfund site, strontium-90 and plutonium-239.”

July 2018

The California Department of Public Health surveys Parcel A and announces that levels of radiation are no higher than what is naturally occurring in bananas.

2020

Retesting commences in Parcels B, C and G.

Land developer FivePoint Holdings files two lawsuits, one against the U.S. government for alleged negligence that allowed the soil sample fraud to take place, and one attempting to place responsibility on Tetra Tech for fraud.

2021

Retesting begins in Parcels C and D.

2023

Retesting begins in Parcels D-2 & UC 1, 2, and 3.

Jan. 17, 2025

Tetra Tech agrees to pay $97 million to the federal government to partially resolve a lawsuit over the falsified soil samples. The settlement has yet to be reviewed by a judge.

Feb. 20, 2025

A judge rejects a settlement for the Bonner & Bonner class action lawsuit from 2018. The partial settlement was rejected by a judge who called the offer of $5.4 million split among 6,500 plaintiffs “paltry.”

Today

The map below summarizes the current state of the cleanup — after nearly 30 years, only two areas have been cleaned up and returned to the city. Retesting is largely to blame for delays.

The complication of sea level rise

The Embarcadero Seawall. Source: Port of San Francisco

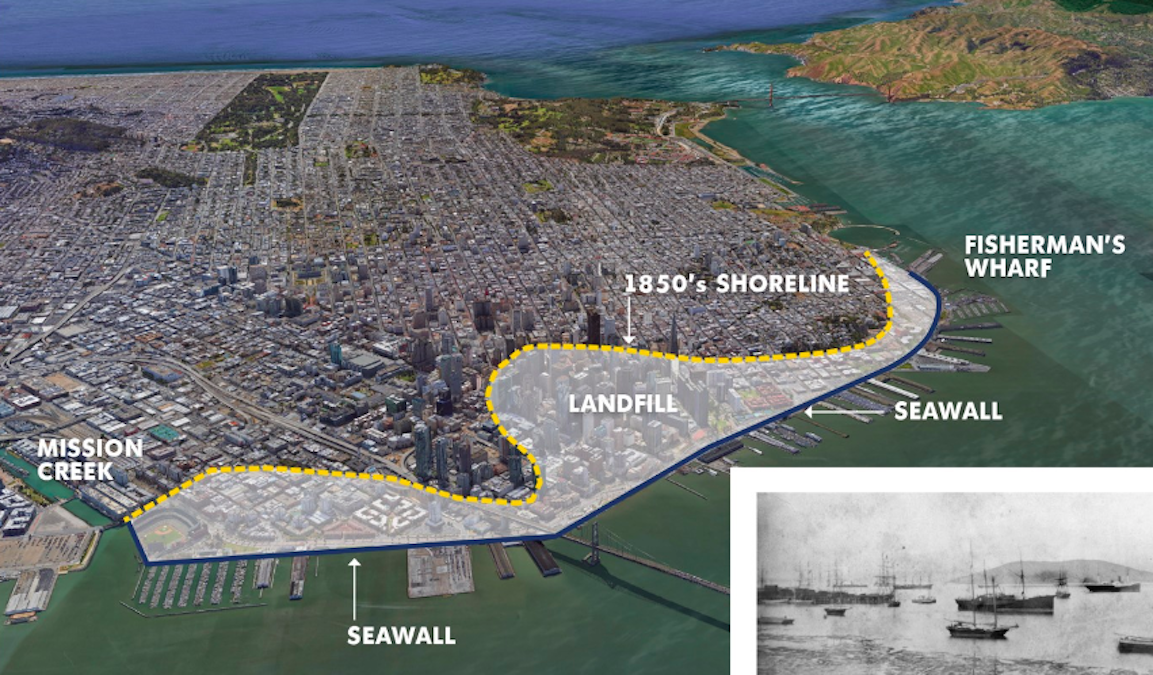

2018

San Francisco voters approve “$425 million in bonds to fund seawall and other infrastructure repairs to the wharves, piers, bulkwall buildings, and other facilities, the tip of the iceberg for the estimated $5 billion project,” according to Mission Local.

The project, run by the Port of San Francisco, would not protect the Bayview-Hunters Point community, leaving community members to wonder: what will? In its most recent report, the Navy indicates that rising sea and ground water mobilizing the shipyard’s toxic waste is a primary concern of cleanup efforts.

2022

A Civil Grant Jury report — which arises from citizen concerns brought to the Presiding Judge of the San Francisco Superior Court — highlights that sea level rise is a main concern for Bayview residents. They find that parts of Parcel G are predicted to be flooded as sea level rises, potentially mobilizing “floodwaters could be poisoned with toxic metals and volatile organic compounds.” In response to these concerns, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission funds an independent sea level rise study in 2025.

Today

The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission contracts Hazen Lee Joint Ventures to run an independent third-party sea level rise study to investigate the risks and possible solutions to sea level rise at the Superfund site. Their findings will be presented to the public in November 2025.

Though an end to the decades-long clean up is drawing near, nothing is guaranteed.

The Hunters Point Shipyard is vast: 849 acres still require cleanup — only 87 acres, the land making up Parcels A-1 and A-2, have finished being cleaned up and were returned to the city for development. The Navy has been working to clean up the other 13 parcels since 1996, an endeavor which may end soon. The final phase will tackle Parcel F, a vast swath of piers and underwater sediment where cleanup is scheduled to begin in 2027.

Climate change and sea level rise may set efforts back, though Michael Pound, who manages the Base Realignment and Closure effort at the shipyard says that the Navy does not currently envision changing the 2036 goal for total remediation, the timeline, set for 2036, has not been set back.

If another radioactive object is found during cleanup, as happened in 2023 when the Navy came across a fragment of glass and a deck marker made with radioactive materials to glow and guide ships at night, delays could follow.

There’s still one more parcel the Navy has not yet begun to work on: Parcel F, which is underwater. There are four more parcels — B, C, G and the utility corridors — where the Navy has yet to finish work retesting soil for radioactive contamination after the Tetra Tech scandal and the demolition of old Navy buildings.

“It’s a very data-driven process,” said Pound to Mission Local. “It’s hard to predict our schedule.”

As the understanding of hazardous chemicals evolves, it’s also an ever-changing process. PFAs, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, were just classified as a potentially dangerous chemical by the Environmental Protection Agency last year. These man-made “forever chemicals” are widely used, but are potentially, cancer-causing.

Because of the reclassification, the Navy’s remediation efforts have been focused on looking for those chemicals too. As the owner of the land and responsible for the contamination that still lingers there, the Navy leads these remediation efforts with their Base Realignment and Closure Program.

Then there’s the Trump administration. Nationwide, federal layoffs have caused many federal departments to reach a stand-still. Pound says many members of the Navy have been offered deferred resignation.

So far, he says the Hunter’s Point Shipyard has been lucky — only one member of their team took the buyout — and it set the cleanup back about three to four months. They’ve had to redistribute the workload, he said, and “everyone has had to take on additional work.”

It’s unknown whether more layoffs are coming and how that would affect the cleanup process. Residents, for their part, are skeptical. Rachelle Holmes is a lifelong Bayview resident and part of local nonprofit All Things Bayview.

“I really don’t believe it,” said Holmes. “They need to start recognizing that people in the Bayview Hunters Point are people … Do they have this going on up in Nob Hill? No, they don’t,” said Holmes.

Meanwhile, community advocates believe being critical of the cleanup process might make their neighborhood safer. “This is about our lives. This is about us being able to breathe,” said Holmes.

We’re more than halfway there!

We’ve raised 2/3 of our $300,000 goal to cover immigration for the next three years of Trump’s term! More than 500 of you have stepped up since September — an incredible feat of community support.

We are humbled. We still have a bit to go: Donate below if you want to keep Mission Local in the courts, reporting on ICE’s actions in San Francisco.