San Francisco’s promise of housing support to RV residents is what Cuevas said she needs, though those options seem far from reach.

She’s been on the city’s backlogged family-shelter waitlist since January. In June, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing reported that 295 families were waiting for shelter.

For now, Lake Merced feels more peaceful than anywhere else she’s parked.

The area is quiet, aside from chirping birds and the occasional car driving by. Between the line of RVs and the lake, residents take evening strolls along a walking path.

Many parked along the road have formed a sense of community. They look out for one another — Cuevas said she once drove a neighbor to the hospital after noticing she was limping — and work together to keep the area clean.

The work boots of Rubén, 23, a Mexican immigrant who lives in an RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a refuge for displaced working families in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

The work boots of Rubén, 23, a Mexican immigrant who lives in an RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a refuge for displaced working families in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“This place is nice and we try to take care of it, because they’re letting us stay here,” said Rubén, a 23-year-old Mexican immigrant who lives a few RVs down. Unlike Cuevas, Rubén chose to move out of a shared apartment and invest in an RV, saving the wages he earns from a street-repavement company.

Residents are able to park on John Muir Drive for months largely due to sparse enforcement, moving their vehicles only for biweekly street sweeping.

Yet even that schedule brings stress, affecting their mental health.

Yuri S., 40, stands outside her RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a parking refuge for working families in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Yuri S., 40, stands outside her RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a parking refuge for working families in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Yuri S., 40, watches her 1-year-old daughter during the day while her husband works, so she’s often in charge of moving the RV every other Monday, despite not knowing how to drive.

When spaces fill up after street sweeping, she sometimes has to park in other parts of Lake Merced that feel less safe, with heavier traffic and unfamiliar neighbors.

“Sometimes I just want to leave as fast as I can,” said Yuri, whose family was pushed out of a shared apartment in Daly City after having a baby last October. “I’m not used to this. Living here in the United States is completely different from anything I was used to.”

Echoes of a displaced community

Some residents now parked along John Muir Drive had previously spent years in even more established RV communities nearby, along Winston Drive and Lake Merced Boulevard. There, they had systems in place to discard water waste, organize trash pickups and coordinate child care.

But last summer, the tight-knit community of predominantly Latino families was dispersed to different parts of the city after one of San Francisco’s most controversial crackdowns. According to Lukas Illa, an organizer with the Coalition on Homelessness, the displacement placed them in even more precarious situations.

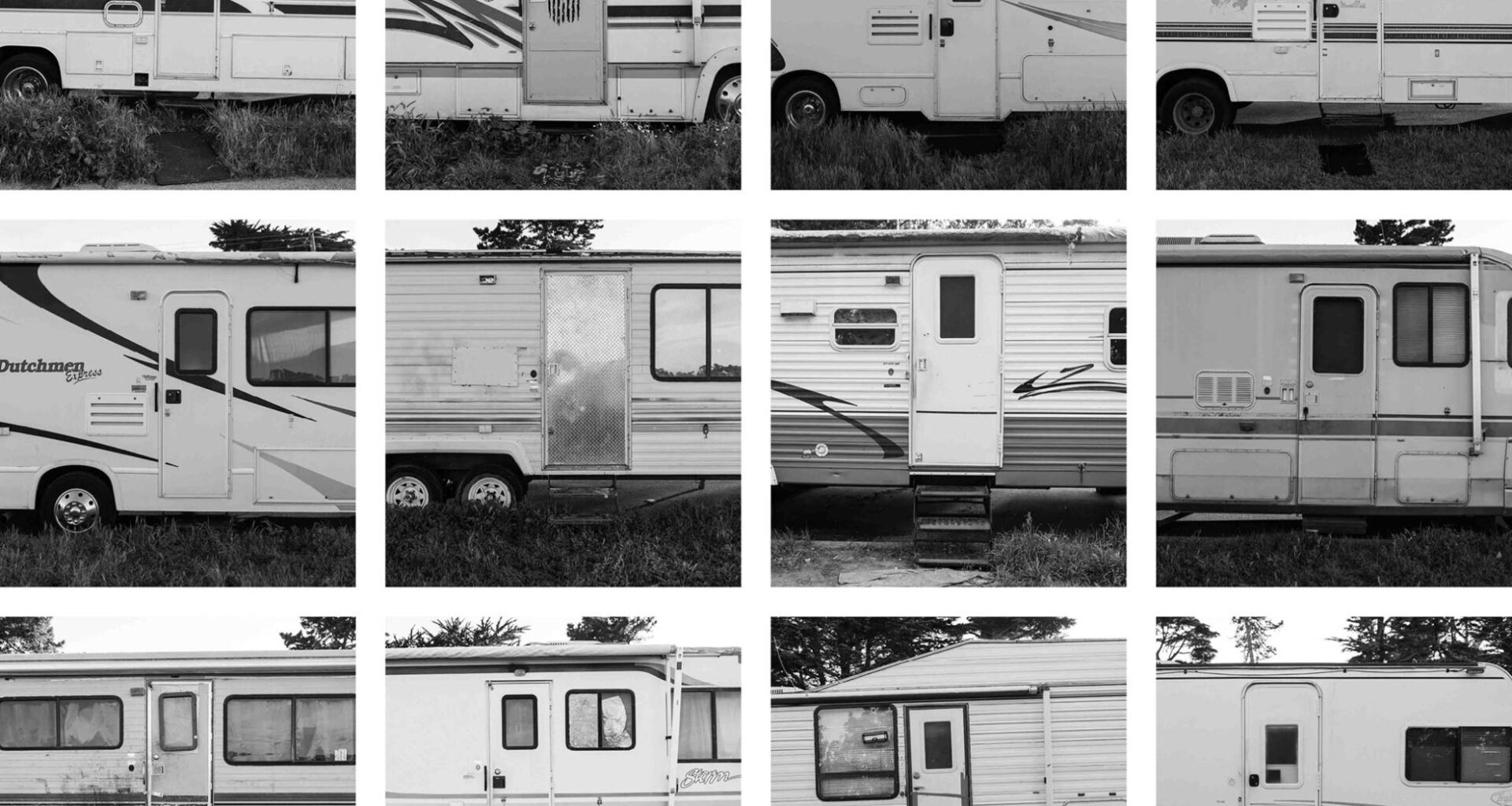

A row of RVs, where many working immigrant families live, lines a street near Lake Merced in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

A row of RVs, where many working immigrant families live, lines a street near Lake Merced in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“Sweeps are not only a means to displace people from a sidewalk, it is a means to break down communities and break down political power,” Illa told El Tecolote. “It breaks down communication channels. It breaks down the community of trust and resource sharing.”

Illa said the mass eviction of a working-class community of families with children on Winston Drive exposed the limits of the city’s goodwill to find compassionate solutions. “We had the most humanizing population,” he said. “And still, nothing was done. It was seen as acceptable to displace them.”

District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar, who represents the neighborhood, has since become a leading voice in regulating and banning RVs citywide. Melgar has framed enforcement as a way to protect RV residents, who she said have faced harassment, vandalism and frequent calls to law enforcement, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement ICE.

Juan Sebastián, 25, a newcomer from Colombia, shows his neck tattoo in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. “I carried my two daughters in front of me with my suitcase on my back,” Sebastián said, recalling his migration through the Darién Gap from Colombia. He and his wife later saved enough money to apply for political asylum and obtain Social Security numbers. “It’s all been thanks to the RV,” he said. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Juan Sebastián, 25, a newcomer from Colombia, shows his neck tattoo in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. “I carried my two daughters in front of me with my suitcase on my back,” Sebastián said, recalling his migration through the Darién Gap from Colombia. He and his wife later saved enough money to apply for political asylum and obtain Social Security numbers. “It’s all been thanks to the RV,” he said. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“We do not have a system to not just regulate but also support these families in an adequate way,” Melgar said on July 15, ahead of the vote to approve the new RV policy. “I think it’s on us to build the system to support people to success, and not pretend that by leaving them on the streets we are doing the progressive thing.”

Even in Lake Merced, where complaints from neighbors are driving an uptick in enforcement on certain streets, RV residents have continued to park and accrue tickets. Vidal Drive, for instance, limits parking to four hours without a permit but remains a refuge for residents like Beriuska Acosta.

“The tickets are piling up, but we have nowhere else to park,” Acosta said. Each one costs $102. “I get stressed out when I see the parking officers coming because you don’t know who you are going to get that day.”

In the Bayview, RV residents are pushed to the brink

While Lake Merced’s RVs sit near water and family housing, those in Bayview–Hunters Point make do in industrial corridors lined with warehouses and empty lots.

Along Jerrold and Barneveld avenues, rows of RVs sit wheel-to-wheel. Children’s bikes and barbecue grills rest outside. On Toland Street, a massive Amazon logo looms over the rows of vehicular homes.

For Laura C., 37, living in an RV is the only option for her family. She rents her vehicle for $1,000 a month from another resident and has been parking along the same Bayview Avenue for months.

RVs are parked in front of an Amazon warehouse in the industrial Bayview neighborhood, where a concentration of families are living inside their RVs, many who are working immigrants, in San Francisco, California, on Jan. 17, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

RVs are parked in front of an Amazon warehouse in the industrial Bayview neighborhood, where a concentration of families are living inside their RVs, many who are working immigrants, in San Francisco, California, on Jan. 17, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“On one occasion, the city came to clear us out,” Laura said. “But to tell you the truth, we came back. There is nowhere else to park.”

District 10 Supervisor Shaman Walton, who oversees the Bayview, was one of two supervisors to vote against the new RV policy, arguing that an enforcement-first approach won’t solve the housing crisis that made RV living necessary.

“To say that someone living in a vehicle does not have a home is malicious when they have no other form of shelter,” Walton said during the board’s vote. “This legislation is alluding to supporting brick and mortar as the only possible home in the most expensive city on the planet.”

With 55% of the city’s RVs parked in the Bayview, Walton’s district is the epicenter of San Francisco’s RV crisis. In emails obtained by El Tecolote, residents described RVs blocking hydrants and generating trash and noise, which they fear deters potential tenants.

Inside the RV the Clavejo family rents for $1,000 a month in the industrial Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Inside the RV the Clavejo family rents for $1,000 a month in the industrial Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Despite numerous 311 reports, many cases are quickly closed as “invalid” or “canceled,” fueling accusations of unequal enforcement compared with wealthier Lake Merced.

Meanwhile, along a number of streets in the Bayview, RV neighbors say they help each other find jobs, resources and care for each other’s pets. Some, like Laura, lend their shower or kitchen to neighbors living in cars.

In September, the SFMTA began taping notices on the windshields of the RVs, warning that vehicles longer than 22 feet or taller than seven feet will risk being towed. The flyers invited residents to informational events and permit workshops.

Sofía, 7, plays on a smartphone inside the RV her parents rent for $1,000 a month in the industrial Bayview neighborhood in San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Sofía, 7, plays on a smartphone inside the RV her parents rent for $1,000 a month in the industrial Bayview neighborhood in San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

The agency is offering six-month parking permits for people who were found parked in the city on May 31, as well as a limited number of housing subsidies.

Permits could be revoked if residents decline shelter services. The city will also have an optional buyback program, paying $175 per linear foot — $1,000 upfront, with the remainder after residents secure housing.

Laura and her husband said they feel reassured by the permit but are anxious that they might be required to give up their RV to qualify for housing, a rumor that has circled among RV communities.

Laura C., 37, checks her DoorDash app from her car in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Laura C., 37, checks her DoorDash app from her car in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

A spokesperson with the Department of Emergency Management clarified in an email that residents can keep their RVs, though they must move them to storage or parking outside the city once the ban begins.

Still, Laura worries that housing subsidies won’t provide lasting relief. She and her husband have struggled to find steady work to cover a full month’s rent, and their rental assistance is temporary.

“You adapt to a place,” Laura said. “We’ve already adapted to the calmness here. So going to a different place is difficult because you’re not sure if you can trust it, you can’t leave your children alone.”

The toll of displacement on fragile communities

As the ban looms closer, many RV residents feel mounting anxiety about their future. Lupe Velez, communications director at the Coalition on Homelessness, said some elderly immigrants she’s spoken with are so stressed they can’t sleep, unsure if they’ll qualify for permits.

“There’s really just so many barriers that they’re facing just to receive this information: cultural, language, generational,” she said. “It’s just really devastating.”

Laura C., 37, pours a spoonful of Gatorade into a cup while her two children eat lunch inside their RV in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Laura C., 37, pours a spoonful of Gatorade into a cup while her two children eat lunch inside their RV in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 3, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

For some residents, giving up their vehicle would mean surrendering their only source of stability. And frequent displacement can disrupt access to medication and healthcare visits, as well as take a steep mental toll.

A 2021 study on Oakland’s RV population, for instance, found that RV residents were often reluctant to seek healthcare or social services because they feared their vehicles might be towed while they were gone.

For Daniela, 37, who lost most of her belongings during a tent sweep five years ago, those fears are constant. She fears leaving her RV for too long, worried that it might get towed. She can’t fathom giving it up for a shelter bed, leaving her five pet dogs behind.

Samir, 8, walks past the RV where he lives with his family in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. He attends Buena Vista Horace Mann K–8 Community School, which operates an overnight shelter for students and families experiencing homelessness. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Samir, 8, walks past the RV where he lives with his family in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. He attends Buena Vista Horace Mann K–8 Community School, which operates an overnight shelter for students and families experiencing homelessness. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“Sometimes I have enough to eat, sometimes I don’t,” said Daniela, who parks her RV in the Bayview by an Amazon warehouse. “I’m always worried about the police coming and taking away my home because it’s the only thing I have.”

Others are cautiously optimistic. Asylum seeker Alexander, 33, and his wife live with their dog in an RV. Increased enforcement pushed them from Vidal Drive to John Muir Drive, and they’re now weighing the city’s permit program — or even its RV buyback offer.

“It’s nice that they’re giving us opportunities,” Alexander told El Tecolote. “That they’re not just putting rules but that they’re giving us a way to move forward.”

Samir, 8, tries to juggle his soccer ball with his feet in the Bayview neighborhood in San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Samir, 8, tries to juggle his soccer ball with his feet in the Bayview neighborhood in San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

A few vehicles down, Mario and Nancy Guardin are more skeptical. They plan to apply for the permit but are wary of selling their RV, worried that once housing subsidies expire, they’ll face homelessness again.

“With a safe parking site, they would be able to solve all these problems,” Mario said. “But they don’t want that.”

With an enforcement deadline looming, the city is deciding where to place the new two-hour parking signs. Mayoral staffer Eufern Pan advised the SFMTA in an email to base the locations on four factors: where RVs are concentrated, where constituents complain most, 311 data, and input from police and parking officers who work on homelessness.

Pairs of shoes dangle above the Bayview neighborhood where a concentration of families are living inside their RVs, many who are working immigrants, in San Francisco, California, on Jan. 17, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Pairs of shoes dangle above the Bayview neighborhood where a concentration of families are living inside their RVs, many who are working immigrants, in San Francisco, California, on Jan. 17, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

For the dense communities of families living in RVs in Lake Merced and the Bayview, it’s unclear whether the new policy will stabilize their lives with more housing opportunities or uproot them entirely through constant tows.

“They have consolidated the RVs to two different spots. It’s the Bayview, it’s Lake Merced,” Illa said. “[It’ll make it easy] for cops to monitor every two hours.”

Illa said a ban on large RVs, a “visible sign of poverty,” will only encourage housed residents to report RVs in their neighborhoods and push families to seek refuge in cars and smaller vehicles.

Laura C., 37, looks out from the RV she rents for $1,000 a month in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

Laura C., 37, looks out from the RV she rents for $1,000 a month in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, California, on April 24, 2025. (Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local)

“It’s a lot harder to stay vehicularly housed in an RV versus like a sedan because the image of an RV is so stigmatized, is so hyper policed, that it is reported the second that it is seen,” Illa said.

From the living room of her RV in the Bayview, Laura looks out over an industrial landscape. Her eyes widen when she thinks about a backup plan.

“This is our home. If they take our homes, we will end up in the street,” she said. “For me, this is my home.”

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.