We work for you — reporting on the stories our community needs. Our journalists attend city council and school board meetings, follow tips and make the calls to keep you informed on the important issues in Berkeley. Will you chip in today to support that work during our year-end fundraising campaign?

Editors’ note: This story was first published on Berkeleyside on Feb. 23, 2025.

On June 27, 1980, Jose Artiga was 23 and two semesters shy of an engineering degree when his family received word that far-right death squads were coming for him and four other college students in his hometown of San Martin, El Salvador.

El Salvador was a year into a civil war that pitted the paramilitary death squads, funded in part by the U.S. government, against Marxist-Leninist guerilla forces and the civilians who supported them. Since the United States did not recognize the Salvadoran civil war, and its role in it, those who fled to the U.S. were not granted refugee status and were instead considered economic migrants.

After his family told him about the order to kill him, Artiga was out of the country by 5 p.m. By that time the other college students were already dead, but their relatives “couldn’t recognize the bodies because they were cut into pieces,” Artiga said.

It took Artiga three months to get to Austin, Texas, and another year-and-a-half to get to San Francisco, where he was given sanctuary at the Most Holy Redeemer Church in the Castro and devoted himself to the solidarity movement in his homeland. In March 1982, Artiga participated in a hunger fast at St. Boniface Church in downtown San Francisco to draw attention to the Salvadoran crisis, making the local news.

The Rev. Gus Schultz, pastor of Berkeley’s University Lutheran Chapel, now considered the father of Berkeley’s sanctuary movement, took notice and invited Artiga to a press conference.

On March 24, 1982, Artiga joined three other Salvadoran asylum seekers as the ULC and four other Berkeley churches — St. John’s Presbyterian, St. Joseph the Worker, St. Mark’s Episcopal and Trinity Methodist — gathered in front of University Lutheran Chapel and announced their commitment to sanctuary and created East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, a grassroots collective to coordinate their efforts to shelter, aid and advocate for the refugees. Reading from their newly adopted covenant, which their congregations had to approve, the churches promised to “provide sanctuary — support, protection and advocacy — to the El Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees who request safe haven out of fear and persecution upon return to their homeland.”

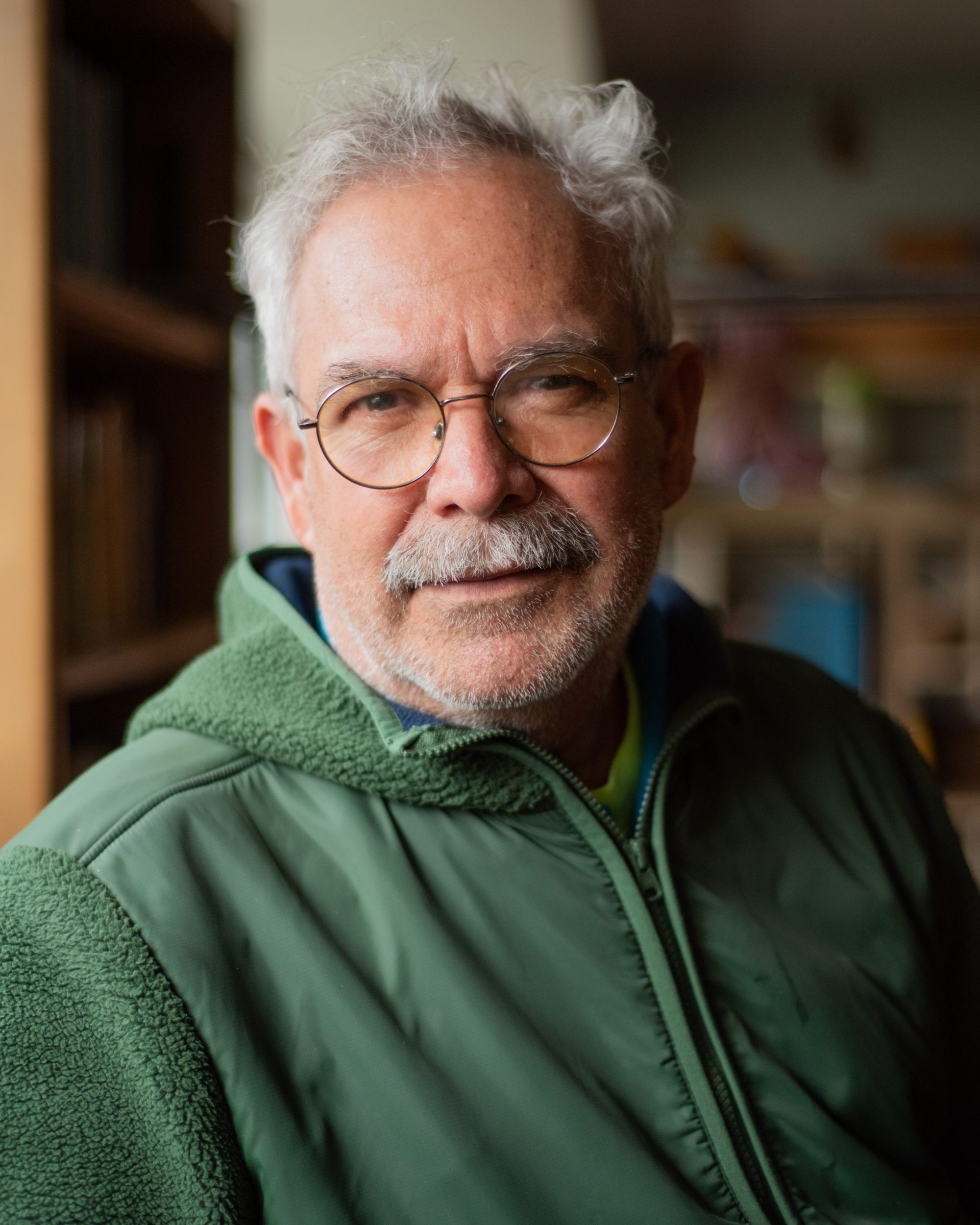

Jose Artiga fled El Salvador as a college student in 1980 to avoid being killed by paramilitary death squads. Two years later he was among the asylum seekers present as five Berkeley churches announced the creation of the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant. He has dedicated his career to advocating for migrants’ rights. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

Jose Artiga fled El Salvador as a college student in 1980 to avoid being killed by paramilitary death squads. Two years later he was among the asylum seekers present as five Berkeley churches announced the creation of the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant. He has dedicated his career to advocating for migrants’ rights. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

The event made the news and it made history, reinforcing Berkeley’s role as the birthplace of the modern-day sanctuary movement, which has its roots in the Vietnam War. The covenant became a model for religious groups around the country.

“What was powerful was what developed after that,” Artiga said. “People began talking about the testimony of a refugee to see if the U.S. policy was justified or not. The U.S. was sending $1 million a day to keep that war going. The questioning of that policy started happening then.”

Forty-three years after that press conference outside University Lutheran, Berkeley churches and East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, now one of the largest pro-asylum programs in the U.S., continue to work on behalf of asylum seekers. Jose Artiga, meanwhile, has returned to the ULC, this time as a tenant heading a social justice organization serving Salvadorans.

All of these efforts, however, are taking place in a more hostile political environment. Instead of testifying as their predecessors did, immigrants today are spending less time in public. President Donald Trump ran a campaign that included racist rhetoric and conspiracy theories targeting migrants, and in its first few weeks the administration has arrested almost 9,000 immigrants and deported over 5,693 people. Because of the Berkeley movement spearheaded in 1982, a larger network of activists that contains not only religious organizations, but hundreds of municipalities across the country that have declared themselves sanctuaries, from the City of Berkeley to the State of California, are prepared to push back against the federal response.

“The Trump administration is attempting to shut down sanctuary, but this is actually not possible,” said Lisa Hoffman, co-executive director of the Berkeley-based EBSC, who has worked for the organization since 2017. “Sanctuary is the spirit of humans coming together to stand up for what is morally and ethically right.”

The origins of sanctuary

University Lutheran Chapel on College Avenue was one of the original institutions behind the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, which became a model for religious groups around the country and today serves immigrants from 72 countries. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

University Lutheran Chapel on College Avenue was one of the original institutions behind the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, which became a model for religious groups around the country and today serves immigrants from 72 countries. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

The term “sanctuary” was first used to denote a sacred religious space that was first in the outdoors and then in buildings such as Hebrew temples and the sacred lodges of the Algonkin and Sioux, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. In Greek and Roman times, fugitives sought sanctuary in temples. Early Christian churches began offering their own protections. By the end of the fourth century, sanctuary was part of Roman law, making it illegal for the secular authorities to remove even a murder suspect who faced the death penalty.

In the novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Quasimodo saves Esmeralda from execution by carrying her into Notre Dame and claiming sanctuary. Clergy relied on the practice to harbor slaves fleeing the American South during the 19th century and to protect European Jews fleeing the Holocaust a century later. The protection of a church was symbolic, a stall tactic providing fugitives more time to negotiate with alleged victims or go into permanent exile.

The Trump administration is attempting to shut down sanctuary, but this is actually not possible.” — Lisa Hoffman, co-executive director, East Bay Sanctuary Covenant

In the Bay Area, there are around 40 sanctuary congregations, according to the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, a statewide network based in Oakland. In light of the recent deportations, the organization was joined by 43 faith organizations and dozens of religious leaders on Feb. 19 to publicly reaffirm their commitment to sanctuary at a St. Mark’s Lutheran Church in San Francisco ceremony.

After Trump’s victory in 2016, about 400 churches nationwide declared themselves sanctuaries, bringing the country’s total number of sanctuary churches to 800, according to the nonprofit group Church World Service.

Though the ancient tradition of sanctuary has appealed to both religious and secular communities, the concept of establishing sanctuary cities and states through legislation is relatively new in the United States.

The federal government has the right to enforce immigration policies, but local laws can set standards on how its law enforcement and other employees interact with federal authorities and define safe spaces within the community, thwarting federal efforts.

After U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) proclaimed arrests would now take place in “sensitive areas,” like churches, hospitals and schools, the Berkeley City Council reaffirmed its commitment to protect such places on Jan. 21. Berkeley’s school board and rent board have made similar reaffirmations.

According to estimates from the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey, roughly 16,000 Berkeley residents are immigrants without U.S. citizenship. That population includes legal permanent residents, and visa holders, such as professors and students. If mass deportations are carried out the way Trump envisions, the focus would be on undocumented immigrants and other groups with statuses that rely on executive orders, such as recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status. Alameda County has an estimated 107,000 immigrant residents who have no legal status. Mass deportations, advocates say, would separate families, disrupt businesses that rely on immigrant workforces, and inundate local courts and jails.

In addition to protecting immigrants on moral and ethical grounds, municipalities have been motivated to enact sanctuary policies because studies have shown that crime has decreased in places that have such policies.

“People aren’t afraid to contact local law enforcement if something is happening,” Hoffman said. “If people feel like the local law enforcement is going to turn them over to ICE, they’re not going to call.”

Roots in the anti-Vietnam War movement

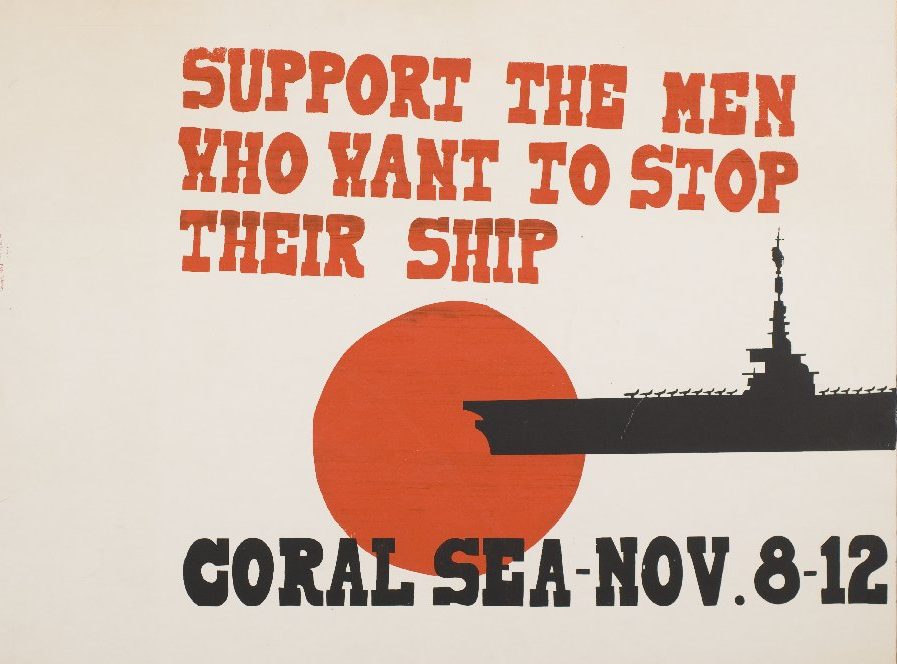

A 1971 poster designed by Doug Lawler in support of crew members of the aircraft carrier Coral Sea who’d signed a petition opposing the Vietnam War. Courtesy: Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi archive

A 1971 poster designed by Doug Lawler in support of crew members of the aircraft carrier Coral Sea who’d signed a petition opposing the Vietnam War. Courtesy: Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi archive

While Berkeley’s role of providing sanctuary is often connected to the plight of refugees from Central and South America, its roots grew from protests during the Vietnam War. From the beginning, the Berkeley sanctuary movement challenged U.S. policy.

“The very first episode of sanctuary wasn’t about immigration at all, it was about conscientious objectors who were stuck in military service,” said Bennett Falk, who had been involved with the local sanctuary movement at University Lutheran Chapel, first as a seminarian and then as a layperson in the early 1970s and 1980s, when Schultz, who died in 2007, was pastor.

Around 1970, one of the members of the congregation burned his draft card on a Sunday in a parking lot behind the chapel, Falk said.

“That whole procedure was observed by the FBI, who were across the street on Haste. We then all went into the church and when they came out after the church service, the FBI arrested him. We weren’t worried about them invading our space,” Falk said.

In 1971, when the aircraft carrier the Coral Sea was set to ship off from Alameda, at least 1,000 members of the 4,500-member crew had formed an organization called Stop Our Ship and signed an anti-war petition. A two- to three-day standoff ensued, pitting federal and state law enforcement against anti-war protestors, the ULC and the City of Berkeley. The city council made history by adopting Resolution 44,784, calling itself a City of Refuge, the first in the nation, for any crew members and designating the ULC as a city-approved sanctuary.

Declaring sanctuary meant that we were committing ourselves to illegally care for these refugees.” — Rev. Robert McKenzie, pastor of St. John’s Presbyterian

On Nov. 13, 1971, the Berkeley Daily Gazette reported that some 1,200 demonstrators who had shown up in Alameda to support the objectors were met by “a massive show” of local, regional, state and federal security. The incident ended peacefully, but 35 sailors did end up going AWOL and one person (not yet in the military) sought sanctuary in the church, according to the Gazette.

On Nov. 9, Schultz held a press conference in the church basement with five of the sailors, according to Found SF, drawing media attention and support from peace activists like Joan Baez and Dorothy Day.

“There were men from the Coral Sea who were through here,” Schultz told the Gazette. “They took advantage of the sanctuary that was offered. They had legal counsel and they had information as to what the church could and could not provide.”

Church council president Susan Ramshaw vowed that the church would continue to provide sanctuary to GIs or “anyone who would like to seek counsel.”

Because of this experience, Schultz thought he could apply the same protections for the many refugees who began flooding into the Bay Area, said the Rev. Robert McKenzie, pastor of St. John’s Presbyterian from 1966-82.

In January 1982, St. John’s received a request to house a couple from El Salvador and their baby because the church had previously taken in two political refugees from Argentina as part of a U.S. resettlement program under the Carter administration. By that time, the government considered those who harbored or assisted asylum seekers lawbreakers.

“Declaring sanctuary meant that we were committing ourselves to illegally care for these refugees,” McKenzie said. “Though we had taken in this couple and provided them with a place to stay, we did not formally say we were resisting the government to do so. The proposal then was for us to challenge the government and its policies against refugees from El Salvador. We were going to stand with these refugees and make it a very public thing to do.”

Joining the Berkeley churches in their groundbreaking efforts was Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona, which signed onto the movement shortly after ULC’s governing board declared sanctuary. Southside Presbyterian likewise held a press conference when the Berkeley churches made their announcement on March 24, 1982.

Carrying on — despite the threat of arrest

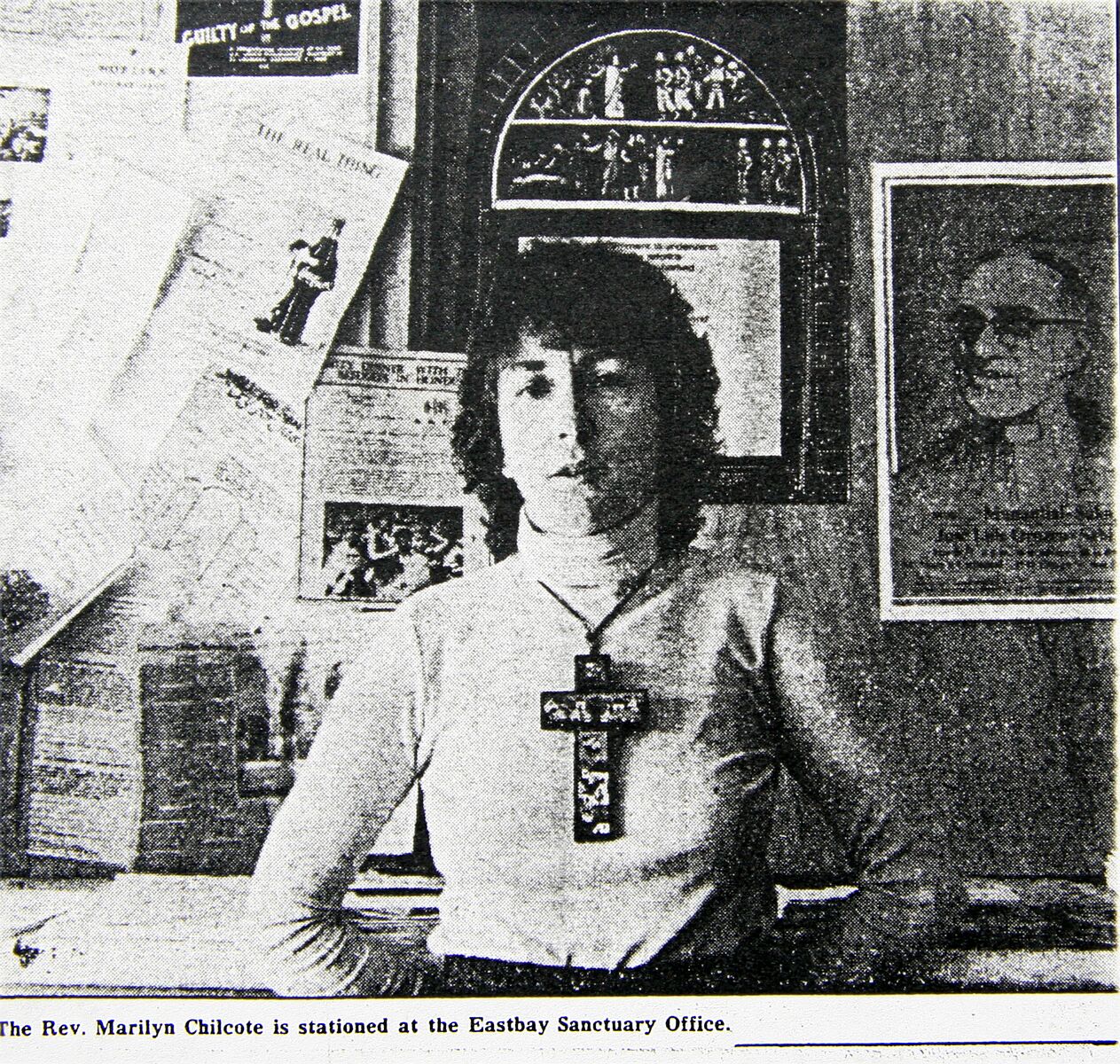

The Rev. Marilyn Chilcote in 1985. She served as East Bay Sanctuary Covenant’s director from 1984-88. Courtesy: EBSC

The Rev. Marilyn Chilcote in 1985. She served as East Bay Sanctuary Covenant’s director from 1984-88. Courtesy: EBSC

For those assisting asylum seekers, the threat of arrest was real. In 1985, 11 members of the Tucson church were arrested on felony charges for smuggling Salvadoran refugees across the border. A year later, a federal jury acquitted three of the workers, while eight were convicted.

“Nobody was arrested here, although we lived under the threat of a $5,000 fine and up to 10 years in jail for harboring what they called ‘illegal aliens,’” said the Rev. Marilyn Chilcote, McKenzie’s wife, who served as assistant pastor at St. John’s from 1981-84. “For us they were just human beings fleeing for their lives. We would hide these people if necessary. ”

After that, the five congregations participating in Berkeley grew to 34, while another dozen in Tucson joined, including non-Christian denominations, McKenzie said. “It really took off.”

Soon the initial idea of using the church building to protect asylum seekers grew into a movement to send church delegations to Salvadoran refugee camps in Honduras to see for themselves what the situation was like.

We lived under the threat of a $5,000 fine and up to 10 years in jail.” — the Rev. Marilyn Chilcote, assistant pastor of St. John’s

“Sending delegations of church people to the camps and parts of El Salvador was an act of solidarity and a way of understanding what the pressures were on them,” McKenzie said. Between 1980-85, around 660,000 refugees were resettled in the United States.

In June 1982, Chilcote spent a week at Mesa Grande, the United Nations refugee camp in Honduras, with Jean Getchell, the wife of the pastor of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, the Rev. Philip Getchell. The camp housed 5,000 refugees, some of whom described how the Salvadoran government was wiping out entire villages, Chilcote said. By the war’s end in 1992, the death squads would be responsible for killing tens of thousands of Salvadorans.

When the ULC’s Falk visited the camp, also in 1982, his delegation arrived about an hour and a half before the Honduran military shut it down.

“We couldn’t get out for a week-and-a-half,” Falk said. “We were there to welcome refugees and get them into the U.N. camp. It was a tenuous situation. We were unarmed and suddenly there was the Honduran military.”

Bennett Falk, who has been involved with the sanctuary movement at University Lutheran Chapel, traveled to Honduras in the 1980s to understand the needs of Salvadoran refugees. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

Bennett Falk, who has been involved with the sanctuary movement at University Lutheran Chapel, traveled to Honduras in the 1980s to understand the needs of Salvadoran refugees. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

McKenzie said that sanctuary churches from California, Oregon and Washington also operated a “refugee caravan” that drove refugees in a convoy of up to 33 cars from Los Angeles to Vancouver, Canada, with overnight stays at churches along the way.

“It was openly and at great risk because we could have been picked up at any time,” Chilcote said. “We were really daring the INS,” the [Immigration and Naturalization Service], “today’s ICE — to come and get us.”

Vancouver is where the two St. John’s asylum seekers ended up — and were offered citizenship.

By 1986, The New York Times reported that the Bay Area was home to an estimated 80,000 Salvadorans, most of whom arrived since 1980, with some 40 churches and related organizations providing services. By that time the sanctuary movement had spread to more than 200 congregations around the country.

As Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum seekers continued to pour into Berkeley, the city council in February 1985 approved a resolution declaring all of Berkeley a sanctuary for undocumented refugees, paving the way for the creation of “sanctuary cities” nationwide.

Facing the latest threats

Jose Artiga, director of the SHARE Foundation — a justice organization that supports the Salvadorans’ fight for human rights — works with Graciela Guardado at the organization’s office inside University Lutheran Chapel. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

Jose Artiga, director of the SHARE Foundation — a justice organization that supports the Salvadorans’ fight for human rights — works with Graciela Guardado at the organization’s office inside University Lutheran Chapel. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

Today, four of the five Berkeley churches that became sanctuaries in 1982 remain.

Trinity Methodist closed in 2020 due to a dwindling congregation and a building that needed extensive seismic repairs. Some of the former members of Trinity still meet on Zoom and continue to this day to make quilts to donate to East Bay Sanctuary Covenant. St. Mark’s Episcopal and St. Joseph the Worker, a Catholic church, does not offer programs for migrants, yet their pastors said they remain committed to assisting congregants if help is needed.

St. Joseph the Worker likely boasts the largest South and Central American population in Berkeley, as the people from those regions are predominantly Catholic. At Spanish mass on Sunday, Feb. 9, Rev. Alberto Perez alerted parishioners to online resources for migrants that the Diocese of Oakland provides.

St. John’s and the ULC, meanwhile, have continued to assist asylum seekers.

“We haven’t really stopped,” said the Rev. Max Lynn, St. John’s pastor for the past 21 years.

The church is currently helping a Colombian family and two large Guatemalan families, as well as a Guatemalan woman whose seven-year quest for asylum has so far cost the church between $25,000 and $35,000.

When refugees show up, Lynn said, they have nothing and are in “deep, heavy need.” The church provides housing, clothes, furniture, school enrollment, school tutoring and legal aid assistance, among other services.

Although the church does have an apartment and has housed refugees, Lynn discovered that that wasn’t the best way to help.

“In the early days of sanctuary the idea was that the sanctuary is going to be in the church. We wanted to make a statement,” he said. “But pretty quickly two things happened: We realized that the biggest need was legal help, and that the best way to get migrants established is to get them into the Latino community so they can find work.”

“In general, Berkeley’s a university town with a bunch of rich people, so it’s expensive,” he said. “There’s really not a core community of Latinos in Berkeley. People want to go where the rent is cheap and there’s a whole bunch of people from their own culture.”

So the church works closely with its sister parish, First Presbyterian Hispanic of Oakland (Primera Iglesia Presbyterian Church) to find apartments in immigrant communities like Oakland’s Fruitvale, where people can also find work more quickly.

Since 2013, St. John’s has also provided down payments on houses for about 70 immigrants and assisted 77 others with housing. About six years ago, the church helped an 18-member extended family of K’iche’ Mayan indigenous Americans from Guatemala buy a house in the Fruitvale section of Oakland they had been renting by rounding up investors and acting as an intermediary.

At the ULC, the pastor, the Rev. Jeff Johnson had a church apartment created in 2016 for Bay Area residents who were worried about then-candidate Trump’s disparaging comments about immigrants. At a press conference, he called for the need for such sanctuaries “in a time of increased xenophobia, where refugees are derided, scapegoated and blamed.”

The number of people who have taken sanctuary within the church spiked between 2015 and 2018-19, when ULC helped at least a dozen people.

Artiga, who was offered sanctuary for his testimony at ULC back in 1982, is now the executive director of the SHARE (Salvadoran Humanitarian Aid, Research and Education) Foundation, a justice organization that supports the Salvadorans’ fight for human rights, economic sustainability and justice, which has an office in the church.

In 1983 he married Eileen Purcell, co-founder of the Archdiocesan Latin America Task Force and the Committee to Stop the Deportations in San Francisco, after she interviewed him about his work. It was her endorsement that led to his sanctuary at Most Holy Redeemer. He became a U.S. citizen in 1992.

As Artiga’s story illustrates, providing immigrants with a place to stay is part of the effort, said Falk, but they also need assistance with the complicated immigration and naturalization process, which churches typically don’t provide.

That’s where the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant comes in.

Expanding the work the five churches began

East Bay Sanctuary Covenant’s office is inside Johnston Hall in Berkeley’s Southside neighborhood. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

East Bay Sanctuary Covenant’s office is inside Johnston Hall in Berkeley’s Southside neighborhood. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

Founded in 1982 by the five Berkeley sanctuary churches, East Bay Sanctuary Covenant started with an $85,000 grant from the Ford Foundation. Chilcote from St. John’s served as director from 1984 to 1988.

“We had representatives from all the congregations to govern the EBSC. We had meetings with 150 volunteers who provided social services, rides to doctors, translation services, helping people set up apartments, providing clothing and funneling donations that came in and services that were helpful to refugees,” Chilcote said. “We didn’t have money to hand out. We had people to help them.”

With a staff of three employees and a budget of about $100,000, EBSC operated out of the basement of the Trinity Methodist Church for 43 years, even after the church closed. The organization moved its offices to the Berkeley School of Theology in August 2024.

“The most important part for me was the advocacy work,” Chilcote said. She set up a speakers bureau and recruited and trained 40 speakers who shared their experiences as asylum seekers with Northern California churches, advocacy and community groups.

What was once a membership coalition of faith-based groups has broadened into a “multi-disciplinary effort,” said Hoffman. But we “stand on the shoulders of those early activists.”

According to its Year in Review, EBSC served more than 12,000 people in 2024 through its hotline, legal clinic, outreach and organizing and had a 98% success rate in winning clients’ asylum cases. The group has also connected 860 people to public benefits like Medi-Cal and CalFresh and provided legal and social services to 650 unaccompanied minors.

EBSC’s mission is to provide legal, social and advocacy programs that serve immigrant communities, helping to create a pathway to citizenship and promote more compassionate immigration policies. The organization has a staff of 35 and an annual budget of $3.5 million.

EBSC serves immigrants from 72 countries, including those in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Nearly all clients are low-income and most reside in the Bay Area, Hoffman said, but also from other parts of California, as well as Oregon, Washington and “a sliver of Nevada.”

Since Trump’s election, the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant has been holding informational workshops for Salvadoran immigrants who are part of the Temporary Protected Status program. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

Since Trump’s election, the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant has been holding informational workshops for Salvadoran immigrants who are part of the Temporary Protected Status program. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

“We’ve always been part of both the local, state and national efforts to protect asylum,” Hoffman said.

EBSC is currently the lead plaintiff in several lawsuits to protect the right to asylum and has worked with the Berkeley City Council to reaffirm sanctuary. It is also working with a coalition on the state level to strengthen the state’s sanctuary law, which took effect in 2017.

Since the 1980s, what has remained constant in the sanctuary movement is the importance of the real-life stories of those who have fled violence and persecution.

“Many people don’t know this history. It’s critical for us to understand that the U.S. bears responsibility for contributing to the conditions that are causing people to flee,” Hoffman said. “It was the early activists who stood up for more just policies under the Reagan administration. What we do now influences generations to come.”

Like the 1980s, the current wave of migration is also fueled by U.S. policies in Central and South America, Artiga said. “Why are so many refugees coming from Venezuela?” he asked. “That’s a rich country.” Part of the reason many are fleeing, Artiga said, has to do with the U.S. oil embargo.

Local groups say they’re better prepared to protect immigrants

The Sunday morning mass at St. Joseph the Worker church, held in Spanish, has been a gathering center for Latino Berkeley residents. Since President Trump’s return to the White House after a campaign rooted in anti-immigrant rhetoric, many congregants have opted to stay home. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

The Sunday morning mass at St. Joseph the Worker church, held in Spanish, has been a gathering center for Latino Berkeley residents. Since President Trump’s return to the White House after a campaign rooted in anti-immigrant rhetoric, many congregants have opted to stay home. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

What is noticeably different between then and now is the level of fear ratcheted up by the Trump administration, affecting both churches and asylum seekers.

The ULC’s Falk worries that the government may actually try to do what the FBI would not do back in 1970: enter the church premises. So the chapel is in the process of creating a plan to train employees on how to interact with any kind of law enforcement on immigration matters.

“In 1982 when we did this the first time, the refugees were quite adamant about publicizing things,” Falk said. Now, many immigrants have shied away from the spotlight.

On Feb. 9, in his weekly letter to the St. Joseph’s congregation, Pastor John Prochaska acknowledged “the fear and anxiety that many immigrants and their families are feeling at this time.” He told Berkeleyside he heard a parishioner was afraid to go to the store. That sentiment was echoed after the Feb. 9 service, when two parishioners who worked as house cleaners said they were spending less time in public. The women also pointed out that attendance at the Spanish mass was down due to fear.

For some Berkeley immigrants, especially day laborers, staying home is not an option. They must brave the threat of deportation to earn a living, often working for less than the current minimum wage.

A stack of “know your rights” cards greets church-goers at the University Lutheran Chapel. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

A stack of “know your rights” cards greets church-goers at the University Lutheran Chapel. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

St. John’s Lynn said the immigrant community in general is panicking, which is President Trump’s strategy. “We’re just trying to hold the line.” If agents of the federal government start coming for the communities they help, “We’re not gonna let that happen,” he said.

Hoffman admits the ramped-up rhetoric has, understandably, sowed fear and confusion among immigrants. But, she believes community-based organizations are now in a stronger position to protect them if a federal raid happens. The groups have better networks and the support of local elected officials, who are also better prepared to protect immigrants.

“We are not in the same position we were during the first Trump administration,” she said. “We have a greater connection and also a deepened resolve to protect immigrant communities, who are our neighbors and friends and coworkers. We live in one of the most diverse places in the United States. This is our community and we will stand up for everyone.”

… We have a small favor to ask.

We work for you to provide free and independent journalism covering the stories that matter most in Berkeley. And we rely on readers like you to make our work possible. That’s why we’re asking you to contribute to our year-end membership campaign today. We’ve set a goal to raise $180,000 by Dec. 31 and we’re counting on readers like you to help get us there.

Your support will enable us to continue doing the work for you and our community to provide the reporting Berkeley needs. So, what do you say, will you join us in doing the work?

“*” indicates required fields