Aubree and Oscar Petersen moved to Sacramento two years ago, putting the higher prices and worries about crime in Los Angeles in their rear view mirror.

Still, it was a gamble for the Petersens and their young daughter, age 5 at the time. The apartment complex that had accepted the family’s application suddenly wanted double the previously agreed upon deposit a week before they were to move in, upping the total cost to about $4,000.

The family moved into a modest hotel as they looked for permanent housing, while Oscar, a meat cutter for a supermarket, settled into his job. Their funds evaporated quickly.

“We were about a week away from living in our car,” Aubree Petersen says.

It was a banner year for housing construction in the Sacramento region in 2024, with more than 12,500 units completed, marking a nearly two-decade high in new housing construction.

The gains were outlined in a “progress report” by the Sacramento Area Council of Governments, a partnership of 28 cities and counties that addresses complex challenges too big for any one jurisdiction to solve.

“The Sacramento region has been making great strides in producing more housing, and more types of housing to meet the needs of the growing population, but there is more work that needs to be done,” says James Corless, SACOG executive director. “Housing markets are cyclical, and this is a high demand region where housing continues to be a challenge.”

Indeed, when it comes to housing availability and affordability, few challenges are bigger — particularly in long marginalized minority and low-income communities. In the SACOG report the Sacramento region encompasses six counties: Sacramento, El Dorado, Placer, Sutter, Yuba and Yolo counties.

In a 2025 housing needs assessment, the California Housing Partnership, a private nonprofit created by the Legislature in 1988 to study and help solve the housing shortage, reported that in Sacramento County, 54,364 low-income renter households lack access to affordable housing. Additionally, 79% of extremely low-income households in the county use more than half of their income to cover housing expenses, in contrast to 2% of moderate-income households.

In 2024 in Sacramento County, only 4,191 beds were available in the interim housing supply for persons experiencing homelessness. Renters in Sacramento County need to earn $34.34 per hour — 2.1 times the state minimum wage — to afford the average monthly asking rent of $1,786, according to the California Housing Partnership.

Those are daunting numbers, says Marsha Spell, executive director of Family Promise of Sacramento, a nonprofit that helps low-income families find sustainable housing.

“There’s a housing complex,” Spell says, “it just was built right off Highway 160, which is not far from our downtown Sacramento office and I checked into them just last week thinking, OK, maybe they’re low income. But they’re $1,800 a month. And that’s not anything that our families — and we just graduated our 428th family from homeless into housing — that they can afford. If they’re able to afford $1,200 we would be lucky and that’s with both mom and dad working.”

Spell has surveyed several multi-unit complexes within a five-mile radius of her office, along the Richards Boulevard corridor running north of downtown into Del Paso Heights, long a hub of Black residents and other people of color. Most started at rents of $1,200.

“And then you add utilities onto that, you know, so they’re looking at about $1,400-$1,500 a month at the ones on Richards, but the new ones that have just been built are just too expensive for any clients trying to get on their feet,” she says.

Family Promise has helped more than 450 families find housing, partnering with several dozen local churches and other nonprofits around the region to house families.

The Petersens were one of those families.

“We were looking online at resources,” Aubree Petersen recalls. “We called 3-1-1. We had reached out to multiple different agencies and we found them on a whim, just through a Google search and we decided to call them and I think they were, like, one of the last people we called. But they had called us back and one of the great things about them is they strive to keep families together, you know — husband and wives and children.”

Through Family Promise the Petersens found a safe harbor.

In Del Paso Heights, Robin Moore established Safe Harbor, a group of five tiny homes in her backyard. The 16-foot trailers are about 81/2 feet wide and 160 square feet. A sixth unit is off-site. It is transitional housing to help families get back on their feet and into permanent residences.

“I carved out about 40-by-40 feet for the project,” Moore says. “I’m located on about 8,000 square feet, maybe a fifth of an acre.”

Family Promise, where Moore used to volunteer, and Safe Harbor have worked together to secure housing for low-income families. The nonprofit subsidizes the rent at Safe Harbor, and also refers families to a transitional housing program offered by the Salvation Army.

“Then we jump into action, create a welcome basket or, if kids are coming in, we get their preferences, their ages and we really try to welcome them in,” Moore says. “It is fully appointed. We don’t know how they are wired when they come. We don’t know what’s been going on. They can come with their clothes on their backs and we got them.”

The average stay at Safe Harbor is about 90 days, but as far as Moore is concerned, “it takes as long as it takes. They can stay with us for up to six months. Everyone is wired differently when they come.”

Since offering shelter during the COVID pandemic, Safe Harbor has helped more than 50 families.

The Petersens stayed at Safe Harbor for about three months, then about a year and half at a transitional housing complex in North Highlands run by Salvation Army.

Easing the housing crisis is being fought on many fronts.

In his first State of the City in October, Sacramento Mayor Kevin McCarty highlighted housing — ownership, rentals and transitional units for the homeless — as a top priority of his administration.

McCarty emphasized that a comprehensive strategy is essential, encompassing case management, outreach, and transition planning. This approach is vital for ensuring residents successfully move from temporary accommodations to long-term stability.

“I’m deeply concerned about this and how it impacts the next generation,” McCarty said during his address.

Two of the tiny homes Robin Moore created in her backyard for people facing housing issues. Russell Stiger Jr., OBSERVER

Two of the tiny homes Robin Moore created in her backyard for people facing housing issues. Russell Stiger Jr., OBSERVER

The mayor discussed plans to make homeownership more attainable and to prevent displacement. His proposal includes a down-payment grant program for first-time homebuyers and expanded rental assistance, funded through a proposed increase in Sacramento’s real-estate transfer tax.

The city, through its Housing Choice Voucher program (formerly known as Section 8), provides assistance to very low-income individuals and families to help them afford decent, safe, and sanitary housing in the private rental housing market.

Through September, nearly $179 million in rent subsidies were paid to landlords on behalf of residents in the program.

There is a waiting list of 97,315 applicants for financial assistance through the program.

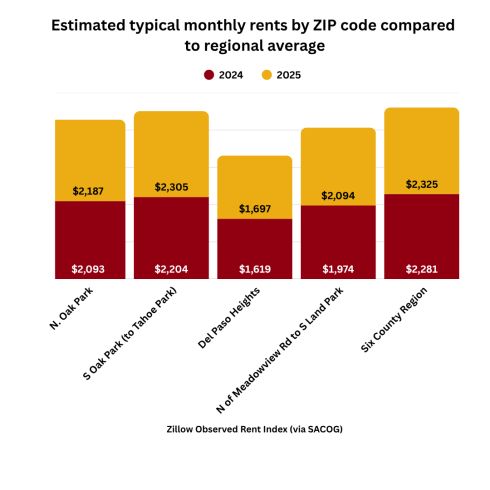

Oak Park, Del Paso Heights, and Meadowview historically have been important centers for African American residents largely due to a legacy of residential segregation and redlining. While these neighborhoods remain significant hubs for the Black community and other people of color, a combination of historical disinvestment, ongoing gentrification, and broader economic challenges has impacted housing availability and homeownership for African Americans in these areas.

Like other areas with historical underinvestment, Del Paso Heights has faced economic challenges. In 2022, there was an abundance of vacant lots in the area. As of 2022, about two-thirds of the population were renters, but the real estate market in the area was active.

Meadowview in South Sacramento is about 25% African American, with a significant percentage of households being owner-occupied as of a 2021 survey, influenced by an influx of Southeast Asian residents. It is one of the communities identified as being historically impacted by disinvestment.

Depending on the location within the three communities of Oak Park, Del Paso Heights and Meadowview, rents and/or mortgage payments can range from 30% to 50% of a resident’s income, according to data compiled by SACOG.

Moore of Safe Harbor called affordable housing in Sacramento a moving target. A person or family, once established in an apartment or home, can suddenly find themselves forced out when the rent is increased beyond their ability to pay.

Aubree Petersen, who now works part time at Safe Harbor, is grateful for the social services agency that helped her family get back on their feet and into secure housing. Her family moved into a two-bedroom apartment a month ago.

“I think about that and I get physically ill because I don’t know where we would’ve been and that’s a scary thought to not know,” she says. “So I don’t have that answer as to what would’ve happened, but I can only imagine that it wouldn’t be good.”

This story is a product of the 2025-2026 Economic Opportunity Lab, an innovative program that champions local journalism by highlighting stories of economic mobility and opportunity in American cities.

Related