Last school year, seven boys from six families met regularly in a Target parking lot off the spider-like network of freeways that winds through the neighborhoods north of downtown Los Angeles.

At 6:50 a.m, the parent on carpool duty would set out westward toward the San Fernando Valley, often cutting the workday short to reverse the commute eight hours later. One dad even rented space at a coworking location to minimize the drive.

The destination: Portola Middle School in Tarzana, one of the Los Angeles Unified School District’s few magnet schools with a program specifically for highly gifted students.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“We were going with traffic both ways,” said Tira Franco, a mom of three who feels lucky that her now-seventh grader landed a spot in the school. But while the boys in her eight-seat minivan spent the trips quizzing each other in math, she quickly grew exhausted. “In L.A., just five miles could take you like an hour.”

Enduring gridlock on “the 405” and other major thoroughfares is part of life in the nation’s second-largest city, and it’s a price that many families are willing to pay to get their children in a preferred school. This year, the kids ride a bus as part of the district’s efforts to expand transportation services. Students who attend magnets and other schools of choice in the sprawling, 700-square-mile district are among those who get priority for a ride. That means the boys get up even earlier to meet the bus.

District leaders in recent years have tried to take some of the pain out of the process by offering choice fairs, a centralized application website and more busing options. But many still find the experience stressful, time-intensive and stacked against low-income families.

“The kids who get a better quality education in the district are the children of parents who are resourceful, who are able to navigate this very complicated formula,” said Elmer Roldan, executive director of Communities in Schools Los Angeles, a dropout prevention program that serves students in 15 schools across the metro area. Children whose parents can manage that system are going to get “the best teachers, best equipment and best experience. Unfortunately, that is not always close.”

Over a third of LAUSD students participate in district choice, officials said. During this year’s application window, which closes Nov. 14, parents can pick from a wide range of options that include not just magnets, but dual-language programs and district charter schools. Families can also request permits to attend a school outside their zone. But that process is time-consuming, and lower-income families often lack the luxury of weeks to research school performance and plot potential routes.

A 2021 district report found that Latino students, English learners and kids from low-income families were underrepresented in magnet programs, which were designed to create more integrated schools. White and Asian students were also overrepresented in affiliated charters — some of the highest-achieving schools in the district.

“There are parent groups in West L.A. that organize information sessions [on choice], but West L.A. is a relatively advantaged area,” said Christopher Campos, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Chicago who has studied public school choice in LAUSD. The single application portal, where parents can request transportation, has made the process “a bit easier. …I still think it’s a pretty daunting task.”

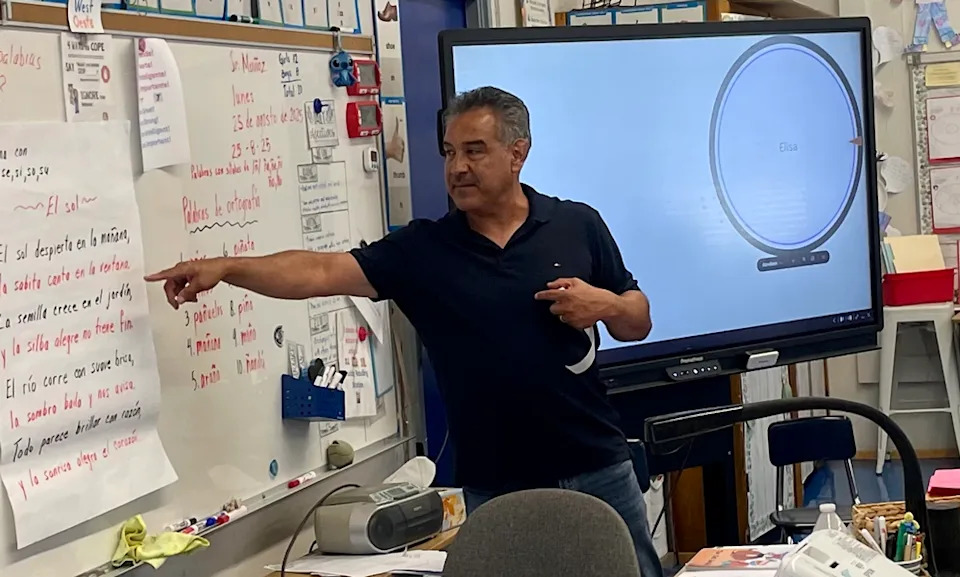

Los Angeles Unified School District has more than 200 schools with dual-language programs, including the Spanish-English program at 135th Elementary School in Gardena. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

‘Valley parents’

For some parents, the process began on a clear Thursday evening in October as they searched for a parking space near a middle school in the San Fernando Valley. Inside the gates, families strolled from booth to booth on the lawn to learn about the district’s array of magnet schools.

There’s Northridge Middle with a special lab for exploring careers in medicine, Robert Frost Middle with a gifted music conservatory and Mulholland Middle, where students in the junior police academy can study crime scene investigation, or law and government. Inside the auditorium, the Louis Armstrong Middle jazz band performed their version of the Edgar Winter Group’s “Frankenstein,” an instrumental rock hit from the early 1970s.

“Valley parents want to stay in the valley,” LAUSD Board President Scott Schmerelson said as he greeted principals and magnet school coordinators, who were busy handing out fliers, buttons and other promotional items. He paused at the display table for Nobel Charter Middle in Northridge, which features a magnet program combining STEM with the arts.

“Here’s Nobel. Always overenrolled. Very popular.”

Students from Olive Vista Middle School, a STEAM magnet in Sylmar, a suburban neighborhood to the north of Los Angeles, promoted their school at a choice fair in October. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

One parent grabbed his attention to suggest organizers set up booths by regions in the valley — east, west and north. “The valley is huge,” she said.

She makes a good point, Schmerelson said.

Research shows that providing transportation increases the likelihood that families will take advantage of school choice, a district spokeswoman said. Officials use social media, websites and other communication channels to inform families that bus service is available. The district is “clustering stops where demand is highest,” the spokeswoman said, but leaders also “continually review ridership data and feedback to explore ways we can improve access.”

Increasing transportation service for students is a priority for Los Angeles Unified Superintendent Alberto Carvalho. (Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Choice options have increased in recent years as the district seeks to prevent an exodus of families leaving for independent charters or private schools. There are over 330 magnet programs, compared to 217 a decade ago. Enrollment decline, which is hurting the district in many ways, has had the effect of opening up more space in many sought-after schools. Students who end up on a waiting list for their first choice are now coming off the list sooner, said Song Lee, LAUSD’s coordinator of student integration services.

But word of events like the fair don’t always reach the parents they were designed for.

“If I would have known about the fair, that would have been helpful,” said Dulce Valencia, a mom of three whose twin daughters are currently part of the Spanish-English dual-language program at San Fernando Elementary School. She has to decide on a middle school for her girls and is considering charters.

Multiple options can confuse parents, Campos found when he held some information sessions regarding another district program called “zones of choice.” Instead of attending their neighborhood middle or high school, students living within one of 17 zones can choose from a menu of specialized schools with themes like global studies, performing arts or social justice.

“A lot of families thought they were showing up to a session about magnet programs,” he said. “They actually were not interested in any of the zones of choice schools, but they were just getting overwhelmed with information.”

‘Have your phone ready’

Once parents secure their child a seat, they still have to figure out how to get there.

“I tell parents, ‘Have your phone ready so you can map out where the school is and you can see if it’s feasible for you,’ ” said Grace Lee, who has two young boys in the district. She also works in the office at Gault Street Elementary, her neighborhood school, and fields questions from parents about choice.

Twenty-seven Los Angeles Unified middle schools with magnet programs were represented at a choice fair at Patrick Henry Middle School in October. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

For Lee, calculating the best routes to school in L.A. calls to mind The Californians, the uproarious “Saturday Night Live” sketch where characters in exaggerated “Valley girl” accents rattle off shortcuts to circumvent the ubiquitous L.A. traffic.

“If you live in L.A. you get it,” Lee said.

When her oldest son got into Oliver Wendell Holmes Middle, north of her Lake Balboa neighborhood, she applied for transportation. But the bus stop was almost as far west as the school was north. She decided it was just easier for her husband to drive him on his way to the office.

Working at a Title I school in the majority Latino district, Lee worries that many families don’t even complete the choice application.

“The people who are in the know, their kids are already fine,” she said. “Their test scores are generally fine.”

Twenty years ago, Lois André-Bechely, a professor emerita at California State University, Los Angeles, wrote in a research paper that parents with flexible schedules stood a better chance of taking advantage of public school choice in L.A. She identified transportation as one of the obstacles.

“Parents who have cars and can arrange time to drive their children to and from school will have more choice options than parents who do not have such advantages,” she wrote.

The city’s Metro system offers free bus and train passes, but some students don’t feel safe on public buses and L.A.’s routes don’t always reach the areas they live in. A recent Wall Street Journal report showed that it can take four times longer to reach a destination by train than by car.

Now retired, André-Bechely no longer conducts research. But as a grandmother, she still hears about parent’s experiences at soccer games and birthday parties.

“Parents still have to be strategic when applying to school choice programs,” she said in an email. “Some school choice issues I identified have not gone away.”

For several years, philanthropies like the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation funded advocacy organizations that guided parents, especially low-income families, through the school choice maze. Their efforts emphasized independent charters, but groups like Speak UP and Parent Revolution, which later folded into other nonprofits, helped LAUSD families as well.

“Los Angeles used to have a robust ecosystem of nonprofits empowering parents and challenging the status quo,” said Ben Austin, a former state education board member who founded Parent Revolution. During the pandemic, he pulled his children out of LAUSD and enrolled them in a charter school. When Eli Broad passed away in 2021, other funders didn’t fill the vacuum, he said. “Eli was such a magnetic leader that when he died, much of the local and national education donor engagement in L.A. died along with him.”

Many families researching options still rely on Facebook and other informal networks, but experience with the process doesn’t necessarily make it easier. With a fifth grader preparing for middle school, Franco, the school choice commuting veteran, is once again weighing school options.

“I’m trying to get her into a great program for next year, and I still have a million questions,” she said. “Why do I have a million questions if I’ve already been through this before?”