Two civil liberties advocates have resigned from Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission and are now speaking out about what they say is a worrisome shift in the way local officials are approaching police oversight.

Brian Hofer, former chair of the commission and District 1 commissioner, and Sean Everhart, commissioner for District 7, tendered their resignations from the civilian-run oversight board last week. Hofer, first appointed when the Privacy Advisory Commission was established in 2016, had been serving in a holdover capacity since his term expired in March. Everhart had served on the commission since 2023; his term was scheduled to end in March 2026.

In recent interviews with The Oaklandside, both gave similar reasons for resigning. Chief among them was that they feel Oakland’s leaders — including some members of the City Council and fellow commissioners — are not doing enough, or don’t care enough, to protect the city from lawsuits over potential violations of Oakland’s own privacy laws.

“Our elected officials seem to think that surveillance technology is the only solution for all the problems, whether it’s illegal dumping or homelessness or violent crime,” Hofer said. “It’s like we don’t have any other solutions other than building these massive systems, and I’m not going to be part of building that.”

Hofer and Everhart accused the City Council of refusing to take into consideration the Privacy Advisory Commission’s recommendations. One of the biggest items to come before the commission recently is a proposal by the Oakland Police Department to incorporate privately-owned surveillance cameras from individuals and businesses into OPD’s monitoring system. The commission has raised questions about this, but Hofer and Everhart believe the council will ultimately support OPD’s plan, ignoring their feedback.

“I felt like nothing I was doing mattered,” Everhart told The Oaklandside.

Hofer also castigated the City Attorney’s Office for, in his view, failing to advise OPD of Senate Bill 34, the state law imposing restrictions on automated license plate reader, or ALPR, systems. “Some of them (the city attorneys) don’t even know half the state laws that exist,” he said. “I’m always the one educating them.”

SB 34 requires local governments and their contractors who operate ALPR systems to have in place security procedures and practices to protect the data they’re collecting from unauthorized third-party access or misuse by the local agency. The law requires the implementation of a usage and privacy policy. According to Hofer, Oakland hasn’t always been in compliance with SB 34.

Hofer also cited concerns with some of the other privacy commissioners “not caring” about OPD violating “sanctuary city” laws that prohibit it from assisting federal immigration enforcement authorities or contracting with companies that do so, though he did not name any commissioners. In 2021, Hofer sued the city, OPD, and the city attorney over the same issue. As part of the settlement, the city paid $30,000 in legal fees and agreed to perform multiple court-ordered reforms.

After more than 10 years of serving on the commission, Hofer said, his breaking point came when he realized he could not improve the culture at OPD.

“If I had a gun to my head and had to pick a primary reason for resigning, it’s that,” he said. “They have zero remorse. They don’t care that the Trump administration is hunting people down, that red states are hunting people down. They’re just sending all this data over illegally.”

Everhart’s resignation letter, submitted on Nov. 2 and obtained by The Oaklandside, echoes some of Hofer’s sentiments.

“I am increasingly concerned that the city is not doing enough to protect residents from emerging forms of surveillance and the risks they pose to civil liberties,” Everhart wrote. “These gaps, in my view, increase the city’s exposure to litigation, and I do not see sufficient action being taken to address those risks.”

He also cited family matters for his resignation.

Everhart told The Oaklandside he was especially concerned about the city’s partnership with Flock Safety, the company that owns Oakland’s network of surveillance cameras. At the Privacy Advisory Commission’s meeting on Oct. 2, an Oakland police representative told commissioners that OPD has no means of auditing the system’s data collection. Several commissioners, including Everhart, said they were concerned about how this could make residents’ data more vulnerable.

“‘Data is the new currency’ is the mindset of the companies we’re contracting with,” said Everhart in an interview with The Oaklandside. “I get the value of the cameras, but the city just doesn’t care about getting sued.”

Some say the Flock cameras are necessary to help victims of crime and police officers. Speaking during the public comment portion of the Oct. 2 meeting, Michael Wimsatt, acting chief of staff for District 2 Councilmember Charlene Wang, said many business owners and workers in Chinatown and Little Saigon feel safer with the cameras in place.

“Access to real-time sharing via these cameras is crucial for OPD to be able to respond quickly and efficiently with its understaffing crisis,” Wimsatt said.

Some elected officials and pro-police activists are increasingly identifying oversight as a problem

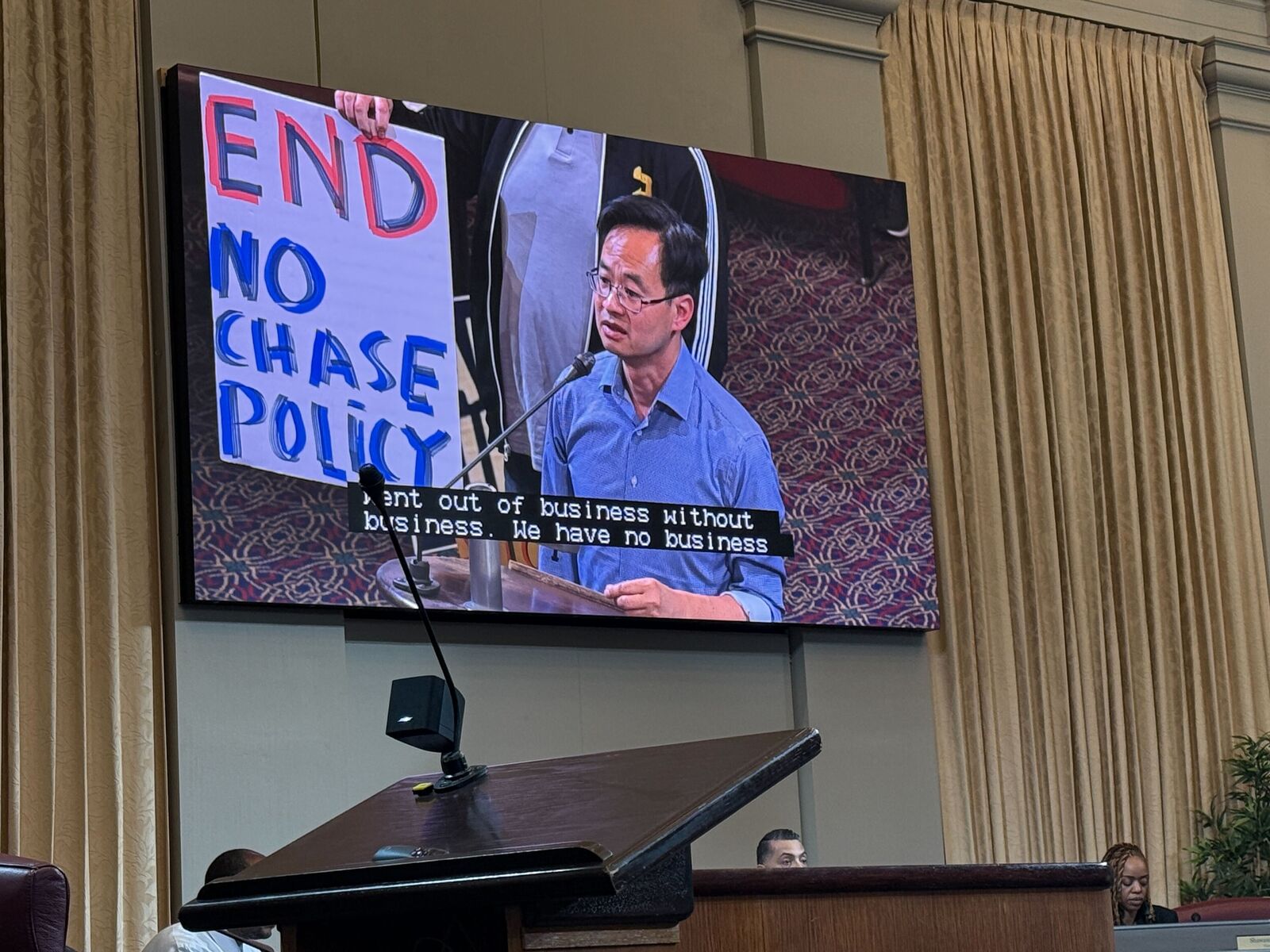

Some community members have accused Oakland’s civilian oversight commissions of obstructing the police department. Credit: Roselyn Romero/The Oaklandside

Some community members have accused Oakland’s civilian oversight commissions of obstructing the police department. Credit: Roselyn Romero/The Oaklandside

Hofer and Everhart’s departures appear to be the result of a growing movement of some residents and city leaders who view civilian oversight of the police and surveillance technologies as an obstruction to public safety.

Rajni Mandal, a District 4 resident, has accused the Privacy Advisory Commission of delaying its vote to approve, modify, or reject OPD’s proposed surveillance use policy. A city ordinance states that if the commission fails to submit its recommendation on the policy to the City Council within 90 days, then the item would be permitted to go straight to the council for approval or rejection.

“It has been 147 days since this was brought forward to the commission in May,” Mandal said at the Oct. 2 meeting. “At this point, the oversight of this commission has become obstructive.”

The Police Commission has also been drawn into the conflict.

On Oct. 21, the City Council declined to reappoint Police Commission Chair Ricardo Garcia-Acosta and Commissioner Omar Farmer. Some council members have been outspoken on social media and at previous council meetings against civilian oversight of the police department. And the vote came after pro-police activists sent a letter to the council criticizing Farmer, in particular, as having a record of “record of overreach, staff interference, Brown Act violations, and unauthorized communications.”

While the Privacy Advisory Commission examines the costs and benefits of many technologies used by different city departments, Hofer said most of the commission’s work involves OPD policies and technologies.

Hofer, who leads the nonprofit civil liberties group Secure Justice, and whose activism helped create the Privacy Advisory Commission a decade ago, described the shift taking place in Oakland as a “war on civilian oversight.”

“Everybody’s blaming civilian oversight for their problems,” he said. “It’s a perfect storm — we’ve got these unsophisticated, loudmouthed people beating on the walls of City Hall, and the electeds love it.”

Hofer said one example of how the public debate has been untethered from facts was seen in the recent push to revise OPD’s vehicle pursuit policy, making it easier for officers to chase. Several years ago, Hofer said LeRonne Armstrong, police chief at the time, told him that Oakland once averaged tens of millions of dollars in lawsuit payouts from car crashes resulting from police chases each year. Starting in 2014, OPD, on its own, changed its policies. The latest change was made in 2022, when Armstrong issued a new order requiring more supervision before and during pursuits. These changes, Hofer said, caused lawsuit payouts to drop by millions.

“That is an amazing policy win,” Hofer said.

But during recent campaigning to urge the City Council to change the chase policy, some community members claimed that it was the Police Commission and other oversight bodies that had restricted officers’ ability to pursue and keep Oakland safe.

More recently, the advocacy group Oakland Report described the often gridlocked policy discussions between OPD and civilian oversight boards like the Police Commission as a “cycle of control, failure, recrimination, and more control.”

This, the group argued, “raises questions about the oversight system’s effectiveness at balancing public safety needs with police accountability, public safety effectiveness, and ethical governance.”

What is the Privacy Advisory Commission?

The Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission debates a controversial proposal to expand the city’s Flock Safety surveillance system during a meeting on Sept. 5, 2025. Credit: Eli Wolfe/The Oaklandside

The Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission debates a controversial proposal to expand the city’s Flock Safety surveillance system during a meeting on Sept. 5, 2025. Credit: Eli Wolfe/The Oaklandside

In 2013, Oakland leaders and law enforcement were laying out the blueprint for what they were calling a Domain Awareness Center — a centralized, live-monitored, and federally funded repository of surveillance cameras, gunshot detectors, license plate readers, news feeds, and first-responder communications systems.

City officials claimed their goal with the Domain Awareness Center was to fight crime and keep the public safe — but, as the East Bay Express reported, the city had planned to use the center to monitor protests, the initial contractor had a history of fraud, and the operational cost to taxpayers was kept under wraps. The push to build a surveillance hub in Oakland also came at the same time that the federal government’s top secret spy programs, scooping up the data of millions of Americans, were exposed in a series of leaks from Edward Snowden and other whistleblowers.

In response to pushback from privacy activists, the City Council reduced the scope of the Domain Awareness Center to the Port of Oakland and Oakland International Airport, rather than covering the entire city. And in early 2016, the council voted to establish the Privacy Advisory Commission, the nation’s second permanent privacy oversight body, according to Reveal. The civilian-run body was tasked with providing advice and technical assistance to the city on surveillance technologies. Its purpose, according to the ordinance establishing the board, is to “protect citizen privacy rights.”

Like the Police Commission, the Privacy Advisory Commission’s members serve in a volunteer capacity and are appointed by the mayor and City Council.

Everhart and Hofer said they feel many Oakland residents and leaders have seemingly forgotten about the purpose of the commission, or no longer want oversight.

Everhart said he initially got involved with the city through former District 7 Councilmember Treva Reid, who, while she was running for mayor in 2022, met Everhart at a community meet-and-greet. At the time, Everhart had been working in the tech industry for 14 years, five of which were at Oracle. He shared his concerns with Reid about the city’s outdated information technology infrastructure.

Six months later, Everhart recalled, he received a call from Reid. She told him the city was hit by a ransomware attack, with hackers stealing city employees’ personal information and other sensitive files.

“I called the ransomware attack six months before it happened,” Everhart said.

During the call, he added, Reid encouraged Everhart to join the Privacy Advisory Commission and appointed him as commissioner for District 7. His term began in March 2023.

Summarizing the recent shakeups on the Privacy Advisory Commission and the Police Commission, Everhart said: “People are leaving commissions because they feel the city doesn’t care.”

“*” indicates required fields