He is credited with mentoring dozens and dozens of teenagers and young men and helping them find their stride.

He is revered for remaining true to the city of Oakland, Calif., staying at a junior college when bigger jobs with better paychecks were his for the taking.

He is regarded as a father figure to students — athletes and others — at the schools at which he worked.

And he is known for being so competitive, he would use 12 men on defense at crucial times in a junior varsity football game because he was confident none of the officials working the game would bother to count the players on the field.

John Beam, 66, was a fixture in the Oakland athletics scene as a high school and then junior college coach. He died on Friday after being shot at Laney College the day before.

Beam was remembered as an unforgettable influence, a man who knew how to draw the most out of his athletes and even his competitors.

“He was a ball of joy,” Chris Kyriacou, who played against a team coached by Beam and coached against and with him, told The Athletic. “He showed his hard shell of discipline, yet he was a very mushy guy that loved people and had a lot of emotion, and that made him a great coach and teacher.”

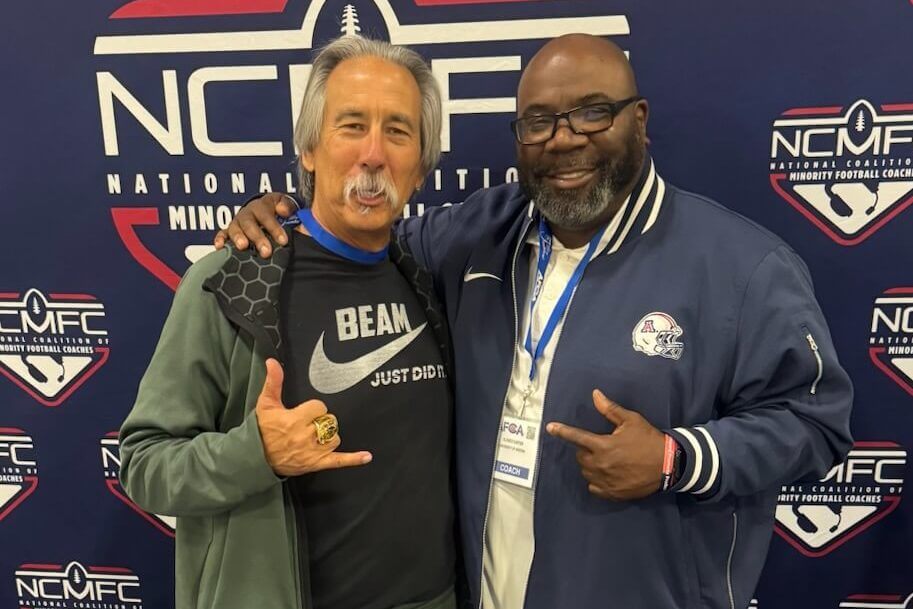

John Beam, left, and Alonzo Carter coached against each other in high school and at the junior college level in the Bay Area. (Courtesy of Alonzo Carter)

Beam became known nationwide after Season 5 of Netflix’s “Last Chance U” featured his Laney team, but his work and his impact in Oakland began long before that.

Portland Trail Blazers guard Damian Lillard, who grew up in Oakland, said in an Instagram post, “Hundreds of kids all over Oakland became the type of men they are today because of this dude.”

Before the Golden State Warriors’ game Friday, coach Steve Kerr wore a T-shirt with Beam’s name and a heart on it. Social media posts from the Cal football team and Oakland native and Basketball Hall of Famer Gary Payton were among many praising Beam’s legacy.

“He had the ability to articulate with a certain population that most people can’t,” said Lou Richie, who attended high school in Oakland when Beam coached at Skyline, then went on to play Division I basketball and now coaches himself at Bishop O’Dowd. “Inner-city kids, that was where he was at home. He was a jewel of our city. It’s a tragic loss to the city of Oakland.”

Kyriacou’s final season of playing high school football was in 1982, Beam’s first season as a coach. He later welcomed Kyriacou onto his staff. After a few years, Kyriacou asked him why his teams could never score in the red zone against Beam’s teams.

“He told me he would play 12 people,” Kyriacou said. “‘There was nobody paying attention.’”

Arizona assistant head football coach Alonzo Carter, who — as the head coach of Contra Costa College and McClymonds High School — coached against Beam, also had recollections of Beam’s competitiveness. One day, Beam suggested that Skyline and McClymonds hold a joint signing ceremony to honor players from both schools accepting offers to Fresno State. On another day, Beam would say he wanted to beat his rival by 40 or 50 points.

Kyriacou recalled Beam co-signing a loan so he could get his first car, and another time bringing the entire football team to his wedding. The microwave Beam gave the couple lasted 20 years, Kyriacou said.

As Beam’s successes and renown grew, colleagues say, he had offers for different jobs in bigger schools. Richie said a shared love — between him and Oakland — made such offers nonstarters.

“He was always going to be about Oakland,” Richie said. “He was always about helping those kids, the kids that people thought were not going to make it. He had the ability to see talent, a lot of times much more so than they saw in themselves.”

Kyriacou said Beam and his wife, Cindi Rivera-Beam, had two daughters and two granddaughters. After giving up the football head-coaching job in 2024, Beam intended to spend more time with his family.

“He was always talking about his grandchildren and how he was excited about that,” Carter said. “I just hate to see his life cut short like that. It is tough to see him not being able to fulfill the things he wanted to do in his retirement.”

One of Carter’s most prized memories of Beam was from a 2022 coaching convention, when Beam asked Carter to pose for a photo with him.

Carter recalled Beam — the standard bearer in his profession, who brought to their matchups respect yet a desire to win as decisively as possible — whispering to him, “I respect what you’re doing and I love what you’re doing.

“We embraced and took a wonderful picture.”