La Niña is still firmly in place as winter approaches. NOAA data released on Thursday shows cooler than average sea surface temperatures continuing across the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, and most models keep the pattern around through winter, although it is expected to remain weak.

That weak signal arrives at a time when many Californians still rely on an old rule of thumb: El Niño means wet and La Niña means dry.

It is an idea that stuck easily. It’s tidy and rooted in real science. But as recent winters have shown, it’s also incomplete and sometimes misleading.

“When El Niño entered public consciousness in the early ’80s, it was tied to one of the wettest winters on record,” said longtime Bay Area meteorologist Jan Null. “Then we hit 1997-98 – another huge El Niño, another flood season. So that idea got cemented. Once it’s in the public psyche, it’s hard to shake.”

La Niña and El Niño are phases of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a climate phenomenon that influences the atmosphere on a seasonal scale. They tilt the odds for storms, but they do not dictate the exact ones that make landfall in California.

Heavy rain causes causes issues for residents in Berkeley, Calif. on Feb. 10, 1998. (Michael Macor/S.F. Chronicle 1998)

“(They) are still the big dogs when we talk about seasonal outlooks,” said Michelle L’Heureux of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. “But (La Niña and El Niño) only shift the probabilities. It’s like being told there’s a 30 percent chance of rain, it doesn’t guarantee anything.”

What ENSO actually tells us

For nearly a century ENSO has been used as the Earth’s metronome by forecasters, a slow rhythm that once gave them a sense of control over global weather patterns. When equatorial Pacific waters warm, El Niño emerges and when they cool, La Niña takes hold.

ENSO’s seasonal influence on California is real, but relatively weak, which means the weather people actually experience is often shaped by faster moving patterns that can either reinforce or completely override the ENSO tilt.

Heavy rain causes flooding on Interstate 880 in San Leandro, Calif. on Feb. 3, 1998 (Michael Macor/S.F. Chronicle 1998)

That fading clarity shows up in the data. Rosa Luna Niño, a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, notes that it’s not ENSO itself that’s changed, it’s the environment that it operates in. “The correlation between Pacific conditions and precipitation was strongest from about 1970 to 1990,” Luna Niño said. “Since then, that relationship has appeared weaker.”

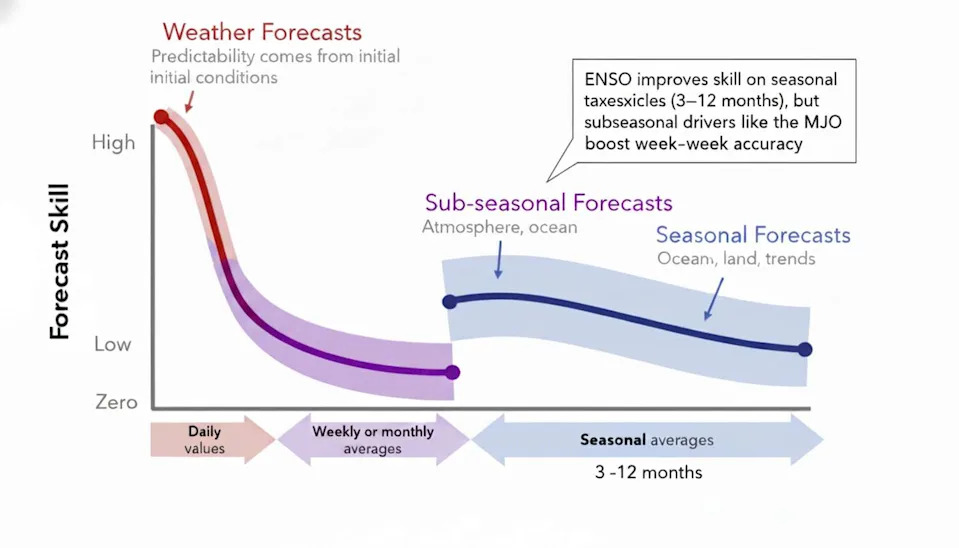

During the seventies, eighties and nineties, the Pacific jet stream often aligned in a way that let El Niño and La Niña express themselves clearly in California’s winter rainfall patterns. In recent decades, that signal has been blurred by sub-seasonal forces that evolve over two to six week timescales. These include atmospheric rivers and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), a pulse of tropical thunderstorms that moves east along the equator.

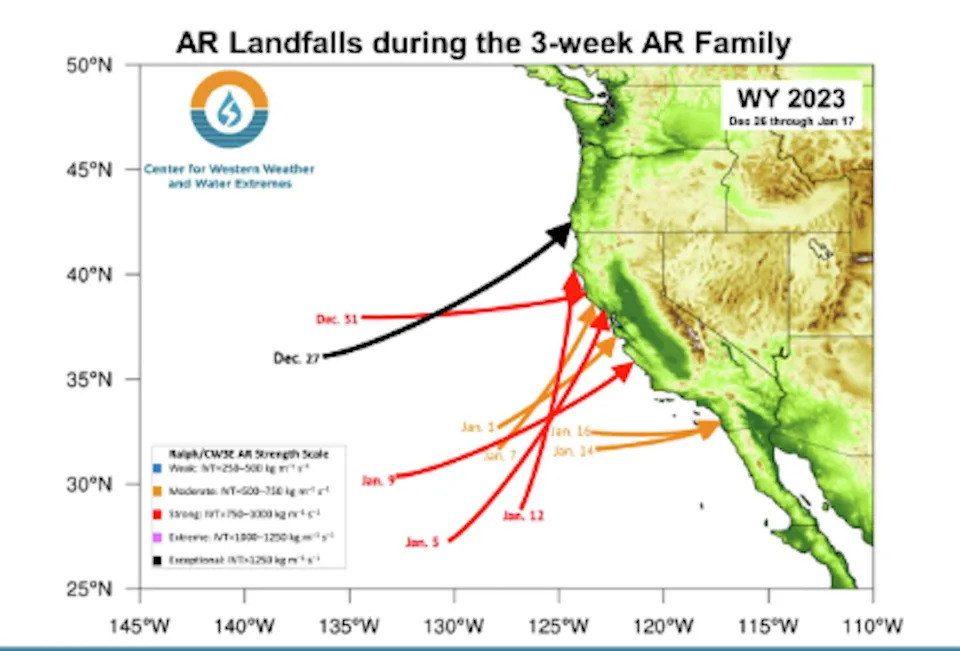

The 2022-23 winter was a case in point. It was the final year of a rare “triple-dip” La Niña with three straight winters of cooler Pacific waters that typically lean towards a dry winter for California. Instead, eleven atmospheric rivers slammed California from late December through January, unloading a season’s worth of rain and snow in a few weeks.

Arrows show the landfall dates and strength of atmospheric rivers that struck California between late December 2022 and mid-January 2023. Each event funneled deep tropical moisture into the coast, a rapid-fire sequence that produced one of the wettest La Niña winters on record. (CW3E)

But this doesn’t mean the La Niña forecast failed. In December, a powerful MJO energized the jet stream, tapping into excess subtropical moisture and pointing it straight at California. In other words, a thunderstorm complex originating over 6,000 miles away overpowered the La Niña background.

Another “off-year” showed the same dynamic from the opposite direction. The 2015-16 El Niño wasone of the strongest on record, the kind that normally signals a wet winter in California. Instead, storms bypassed the state as a stubborn high pressure system blocked the coast. Later research traced the culprit to unusually warm waters and convective activity in the Indian Ocean, which nudged the jet stream north and steered moisture into the Pacific Northwest.

Schematic showing typical forecast skill relative to forecast range (or lead time), and main sources of predictability, for three types of weather and climate forecasts: short-range weather forecasts; sub-seasonal climate forecasts, and seasonal climate forecasts. Source: “Colorado River Basin Climate and Hydrology: State of the Science” by Jeff Lukas and Elizabeth Payton (University of Colorado)

This is exactly the kind of pattern that confuses the public. A strong El Niño on paper, but a remote ocean forcing ended up steering the storm track.

Even in years when rainfall patterns line up with La Niña expectations, the match can be deceptive. Research shows that during anomalously wet La Niña winters, short-term sub-seasonal patterns, like the MJO or atmospheric river alignments, can be roughly an order of magnitude more influential on winter time precipitation in California than the background ENSO state itself.

Why phase labels alone don’t deliver a forecast

The challenge for forecasters isn’t only that subseasonal forces can overpower ENSO, it’s that the very baseline used to measure ENSO is changing. As the Pacific warms, the 30-year “normal” sea-surface temperatures used to classify El Niño and La Niña have crept upward. That shifting yardstick blurs where one phase ends and another begins and can misclassify borderline events, confusing both forecasters and the public.

To keep pace with that warming background, NOAA and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) have both begun revisiting how they calculate and categorize ENSO events.

But even with clearer definitions, one problem remains. Knowing the ENSO phase is not enough. Two winters with the same ENSO label can deliver completely different outcomes depending on the jet stream, the storm track and the sub seasonal patterns that sit on top of the ENSO background.

That is why researchers are turning to something else entirely, a signal hidden not in sea surface temperatures but in the winds that steer storms across the Pacific.

From ocean phases to storm patterns

So if ENSO alone cannot tell Californians what kind of winter to expect, what can?

Forecasters are changing both how they track seasonal influences and how they communicate them.

On the tracking side, the focus has shifted toward how ENSO’s slow background signal interacts with the faster patterns that actually decide whether California floods or stays dry. Instead of asking “Is it El Niño or La Niña,” they are asking “How is that phase coupling with the jet stream right now.”

At Scripps’s Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E), researchers start with ENSO as a broad oceanic tilt, then layer in subseasonal predictors like the MJO and atmospheric river probabilities to see how the signal might play out locally. Their Atmospheric River Scale turns that complexity into practical guidance for flood forecasters and reservoir managers.

Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) use a similar approach, grouping wet winters into recurring jet-stream configurations that often emerge when ENSO aligns with certain subseasonal regimes. These patterns can sometimes be predicted weeks ahead, bridging the gap between ENSO’s seasonal rhythm and the weather Californians actually feel.

Basically, California’s winter outlooks still start with ENSO, but the season is ultimately shaped by the faster patterns that steer storms in real time. That is why researchers are shifting to pattern based tools that link the slow background with the week to week jet stream behavior.

“ENSO sets the background,” L’Heureux said. “But for this region, the week to week patterns decide the impacts.”

This article originally published at California’s rule book on El Niño and La Niña is broken.