California has always burned.

The Golden State has always had a fall fire season, but it now starts earlier and is considered a year-round threat. The climate and topography of the world are changing. And the toll of January’s Altadena and Pacific Palisades infernos, is, by every measure, grimly unprecedented.

Indeed, the face of Los Angeles changed forever once the smoke had cleared from fires that killed at least 30 people directly and an estimated 410 additional people from linked factors. Countless animals perished. Some 18,000 homes, schools and businesses vanished, a trauma that will reshape thousands of lives for decades to come.

Yet, as Californians — and as Bruins — we have always learned to adapt, to come back stronger and smarter than ever. In the case of the L.A. fires, we are guided by UCLA researchers seeking answers on how to predict, mitigate and battle wildfires in a world where climate change and other risk factors have made them increasingly inevitable.

Bruin experts helped shape the national conversation during January’s fires by dispelling myths and misinformation and providing reliable, evidence-based information in real time. Through a shared lens of science, accountability and compassion, UCLA researchers worked tirelessly to help people in Los Angeles and beyond better understand the causes, concerns and consequences of this disaster — many of them doing so at the same time their own homes were under mandatory or potential evacuation zones.

Angelenos saw the fires coming from a long way off. Onetime UCLA Extension student Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower foresaw a massive fire in Los Angeles in 2024, mishandled by a newly elected president who ran under the slogan “Make America Great Again.” (Eerie. You can look it up.) Most of the happy places Butler knew in her hometown of Altadena are now gone. Joan Didion wrote frequently in The Atlantic about fire anxiety in L.A., once watching the Palisades burn (during the 1978 Mandeville Canyon Fire) from her Brentwood home, where she kept a box of family photographs by the door in case she had to evacuate.

As puzzle pieces fall into place — from the arrest of a Palisades fire arson suspect to the filing of multiple lawsuits related to malfunctioning electrical equipment in the Eaton fire — our understanding of even more foundational factors sharpens as well: chaparral bone-dry conditions after eight months of no measurable rain, and 80 mile-per-hour Santa Ana winds zigzagging embers down the canyons. The emergency response was heroic, generous and, occasionally, a little blurry. The blame for the fires’ spread and scale manifested quickly, the tragedy politicized and litigated.

It all feels so grim. And hopeless. But it’s not.

Can We Really Prevent Wildfires?

Despite the wealth of our state, the fourth-richest region in the world, even can-do Californians sometimes feel overwhelmed by what seems the Sisyphean challenge of preventing fire. But Professor Alex Hall, director of UCLA’s Climate & Wildfire Research Initiative, remains heartened by UCLA’s rise to the challenge, with people helping each other in the strong tradition of Bruin service. Campus researchers across disciplines are producing data-driven insights that could shape how we more effectively deal with fire risk and the next conflagrations.

Courtesy of Alex Hall

“I don’t think the apocalypse is inevitable,” says Alex Hall about the continuing risk of wildfires in California. He takes inspiration from UCLA’s response to last January’s fire crisis, efforts he says reflect True Bruin values.

Hall says that as residents of California, we all need to thoughtfully reconsider our relationship to the landscape: Fire-prevention strategies differ between Northern and Southern California, for example. While the causes of fires — “ignitions” — can be natural or human-sparked, fires in Southern California very rarely occur due to natural ignitions.

So although we can’t prevent lightning or high winds, we can minimize human activity in high fire-hazard areas when the risk is elevated. We can also invest in repairing aging power lines, especially when they might come into contact with extremely dry vegetation. Underpinning our response, Hall adds, should be better coordination of all the agencies involved in predicting weather events, managing our energy infrastructure and protecting our wild spaces.

In navigating these challenges, we are far from alone. Wildfires from Australia to Greece provide ample evidence that this is a global phenomenon. Today, Hall is leveraging advances in machine-learning technology to analyze massive amounts of data to create models that can better predict future fire patterns as the climate changes. In fact, he and his colleagues have long projected this climate-driven increase in wildfires. In January, building on their ongoing work, they were able to quickly turn around a study that showed how — and to what extent — climate change contributed to the severity of the L.A. fires.

As Sacramento leaders currently work through a suite of policies aimed at ensuring a more resilient and sustainable approach to living in California’s wildland-urban interface, Hall will work to make sure these decision-makers have the opportunity to ground their work in the best science UCLA has to offer. After all, he already has the deep relationships with state and federal agencies that will ensure UCLA has a seat at the table as key policy decisions are made going forward.

“I would strike a note of optimism,” he says. “I don’t think the apocalypse is inevitable. It’s within our grasp to reduce harm to our communities and our environment. We cannot allow fear to deprive us of agency. We just have to work together — smarter.”

Courtesy of LAFD

An LAFD firefighter battles flames during the Palisades blaze. The total damage of the fires is estimated to be anywhere from $135 billion to $150 billion.

On the Fiery Frontline

It may not have been the apocalypse, but it was a crisis like no other, says Captain Ian VanGerpen, who manages the UCLA-focused Fire Station 37 on Veteran Avenue.

His 12-person team, working with UCLA Fire Marshal Ricardo Barboza, usually responds to around 20 calls a day. During a typical shift, they deal with Westwood car accidents, health emergencies and domestic blazes — not the “hellscape” they faced in the Palisades over a nonstop struggle that lasted 14 days.

“I have been a firefighter for 20 years, during a time when chaparral fires have grown considerably more frequent and dangerous, and in the military before that, and I have never witnessed devastation like it,” he says. “The lethal combination of dry vegetation and high whipping winds meant the fires behaved weirdly, randomly, taking one home and leaving [a house] next door alone, igniting buildings through the attics as well as coming up through the crawl spaces.” You can almost see the tension returning to his shoulders when he recalls it all. “It was,” he says, “insane.”

Firefighters pushed up Sunset into the Bluffs, saving a church and helping evacuate residents; the next day, the crew pushed on, putting out hot spots that kept stubbornly reigniting. “It was traumatic for the families who were evacuated, especially the older people who have lived here for decades, as well as for my people,” VanGerpen says. “I made it a point to sit down with them and find out if they were all right.”

Adjunct professor of chemistry Derek Urwin ’03, M.S. ’17, Ph.D. ’22 — also a veteran L.A. County firefighter — is conducting research focused on improving the safety of firefighters exposed to household fallout, including benzenes, hydrocarbons and formaldehyde. The cancer rate among firefighters is 9% higher than the rate among the general public.

Courtesy of LAFD

The crew of Los Angeles Fire Department Station 37, located on Veteran Avenue, which serves UCLA’s Westwood campus and the surrounding area. The station was critical in assisting stations in the Palisades and Altadena battling the fires.

“In a nutshell, the L.A. wildfires presented substantial exposures for people involved,” he says. “We’re working hard to make sure that we can quantify both exposure and effects as it relates to the health of first responders.”

VanGerpen is keeping a close eye on this UCLA work. “My father was a firefighter who died of cancer in his 60s,” he says. “Only now do we know the risks of toxins which can reach our skin from turnout [protective] gear. Who knows what we have brought back from the Palisades? But we are vigilant as never before thanks to such research.”

The Financial Cost of It All

Despite the extraordinary courage of the firefighters of Station 37 and others, more than 6,000 structures were destroyed in Pacific Palisades, a coastal oasis beloved for its sheer beauty, comfortable friendly neighborhood vibe and low-key celebrities.

More than 9,000 structures were ravaged in the Eaton fire in Altadena alone, an unincorporated township 14 miles northeast of downtown L.A. famed for its historic African American community, adventurous food and art community — and a weirdly world-famous (and beloved) bunny museum that also tragically burned to the ground.

How will this affect the city’s already critical housing shortage? It’s a question UCLA researchers are aggressively addressing. “Judging by other California fires, there will be an immediate surge in house prices and rents,” says Shane Phillips, who manages the housing initiative at the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, “But because we only lost a small fraction of L.A.’s total housing — L.A. County has more than 2.5 million homes — that will settle down in a couple of years. It does, however, deepen the challenge of making housing affordable again.”

John Harlow

A hazardous check at a home in the Palisades section. Permitting for rebuilding has been slower than many had hoped.

In February, Zhiyun Li and William Yu of the UCLA Anderson School of Management estimated that the fires may have caused up to $131 billion in property and capital costs — exceeding every other natural disaster in U.S. history except 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. A month later, the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate released a report in collaboration with the Urban Land Institute Los Angeles and the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate outlining their advice for “rebuilding Los Angeles” after the fires; they also catalogued their postfire actions and resources for use by the public.

As many have already discovered, navigating the politics of home insurance and getting properly compensated for their losses can be a nightmare. Unfortunately, the UCLA Anderson research proved prescient in its suggestion that many residents would discover they were underinsured in the private sector and not covered fully under the state’s “FAIR Plan” backup insurance program. Roughly 15% of Eaton fire victims and over 30% of those affected by the Palisades fire were uninsured, lacking coverage from either private insurers or the California FAIR Plan.

Rebuilding for the Future

There is a profound human need to rebuild swiftly and re-create familiar neighborhoods. But there’s also an opportunity to build better. To employ new materials and layouts to mitigate future disasters. And to rethink what’s needed in order to not just re-create communities but reimagine them.

Mohamed Sharif, associate adjunct professor in UCLA Architecture and Urban Design, and architect Greg Kochanowski M.A. ’99 are co-leading a task force that brings together experts from the American Institute of Architects and federal and city officials to assist communities and advance strategies around wildfire risk and resilience. With three overarching objectives — to mobilize expert members, coordinate volunteer efforts and develop a comprehensive plan — their work complements the role of the independent blue-ribbon commission announced in February by Chancellor Julio Frenk and Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath.

Read a reflection from Chancellor Julio Frenk and explore a timeline of historic California fires here.

Drawing on insights from more than 40 UCLA scholars across campus, UCLA’s blue-ribbon advisors, led by Megan Mullin, faculty director at the Luskin Center of Innovation, Julia Stein, deputy director for the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at UCLA Law School, and the aforementioned Alex Hall, also director of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and UCLA’s Sustainable LA Grand Challenge, contributed their expertise. Their recommendations to the commission, presented in June, call for a “safe and resilient recovery and rebuilding effort” in the wake of the wildfires.

Recommending the creation of two governance structures — a Resilient Rebuilding Authority and an L.A. County Fire Control District — the commission’s suggestions included creating vegetated buffer zones, strengthening water system resilience and safety, coordinating retrofitting in at-risk communities and accelerating the transition to clean, resilient energy.

“An uncoordinated race to rebuild will amplify inequality and leave people at risk of future fires,” Mullin says. “This commission seeks to change that with thoughtful, data-driven policy solutions to build resilient communities for the future we are facing.”

What the Fires Left Behind

One quirk you’ll notice if you visit the rapidly greening Palisades townscape today, from the middle-class Alphabet Streets to the tony heights of the Riviera: the survival of washers and dryers. Hundreds of the machines still stand proud amid the rubble of their residences.

Other junk was swept into the Pacific Ocean, littering beaches 50 miles away and sickening fish and dolphins. Yet more dangers remain in the soil, warns Sanjay Mohanty, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. This fact inspired him to conduct free daily soil testing in the Palisades and Altadena to warn residents about what they were dealing with.

“Some locations are contaminated, and others are not — every property is different,” he says. “Just because your neighbor has high pollution doesn’t mean that you will, but without testing, we’ll never know.” Mohanty is currently working with a multiagency initiative called Community Action Project Los Angeles (CAP.LA), which is helping homeowners decide when it’s safe to rebuild.

Soil testing will continue until December 31, 2025, or until investigators finish all 3,400 sites for which it’s been budgeted. Mohanty stepped in after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which normally conducts such tests, controversially decided not to dig deeper than six inches. “Previous sampling shows that at least 20% of the sites will still be unsafe after removing soil [from the top six inches], and therefore requires further scraping,” Mohanty says. “That’s why CAP.LA is doing the tests for homeowners, so that we can at least give that data to them for peace of mind.” And potentially save them thousands of dollars.

Courtesy of Sanjay Mohanty

Mohanty’s team tests the soil. Health risks from what was left after the fires were extinguished inspired the UCLA associate professor of civil and environmental engineering to begin free daily soil-testing in the Palisades and Altadena to inform residents of potential health risks.

“Fire is always going to be a part of our lives in Los Angeles, and those of us who were not personally affected this time may be in a different position one day,” Mohanty adds. “I’m proud of all the different ways my colleagues across UCLA are working to make sure that we give people the information and resources they need to recover now and prepare for the future.”

Another abiding issue is air quality. In March, Professor Michael Jerrett of the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health warned that some people would return to homes engulfed in “toxic soup.” His research found that wildfire smoke caused more than 50,000 premature deaths in California between 2008 and 2020. Professor Yifang Zhu Ph.D. ’03, Jerrett’s colleague at the Fielding School, says that air pollution peaked on January 8 and 9 during the fires, with southern Los Angeles County hit the hardest. Although air quality outside the burn areas quickly returned to pre-fire levels once the flames were extinguished, further testing near the burn sites is essential to fully understand potential health risks for nearby communities.

In July, Zhu’s team of UCLA researchers completed installation of 20 air-quality monitoring stations in West Los Angeles so residents will know at the hyperlocal level whether the air is safe during debris cleanup or future fires. A similar effort is now underway in the Altadena-Pasadena area.

Acts of Kindness and Connectivity

When the fires ignited on January 7, forcing more than 200,000 people to flee their homes, UCLA responded quickly to the crisis.

Sarah Dundish ’05, chief of staff and director of UCLA Housing & Hospitality, says that emergency shelter was found for hundreds of displaced UCLA students, staff and faculty across the region, including five families who temporarily moved into villas at the UCLA South Bay campus in San Pedro. Families stayed for anywhere from one to seven months before being able to obtain alternate housing; helping them meant a lot to the UCLA staff.

Kimberly Ramsay, event manager and community liaison for UCLA South Bay, was nervous she wouldn’t be able to offer enough comfort or assistance. She soon found that members of the first family to move in were more concerned about showing their gratitude to her and to UCLA.

“From before they arrived to the day they left, they were so impeccably lovely and resilient — even though they lost their home and belongings, they went out of their way to be so thoughtful and helpful to me when I was trying to help them,” Ramsay remembers. “I will never forget them and the way they responded to such a traumatic experience with optimism and kindness.”

The UCLA Research Park FEMA recovery center was a hive of activity during the fires, offering support, information and resources to those affected. UCLA pivoted quickly to open the center to address the needs of the community.

UCLA also offered its new Research Park building at Pico and Westwood boulevards as a disaster recovery center, working with Jenny Delwood ’06, L.A. mayor Karen Bass’ deputy chief of staff; Los Angeles City Hall; and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Operations forged ahead, even as construction continued on the former mall, with its exposed electric wiring and a shortage of working bathrooms.

“Chancellor Frenk, who had only been in office two days when the fires blazed, immediately signed off on the project of preparing the unrenovated west end of the park,” says UCLA’s Jennifer Poulakidas ’89, associate vice chancellor for government and community relations. “Within three days we had made it safe, with tables set up to help people recover legal records, access social services and start rebuilding their lives.”

Not far away, at the Westwood Recreation Center, 240 evacuees were housed in the gymnasium. Those needing emergency medicines or dealing with smoke inhalation received welcome aid from the UCLA Health Homeless Healthcare Collaborative and its mobile medical units.

“Our teams are great at connecting people, not only ‘What do you need physically?’ but also ‘I am here to listen to you,’” says program director Brian Zunner-Keating. Indeed, thousands of Bruins pitched in to help in the wake of a disaster that brought back memories of the scale of devastation of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

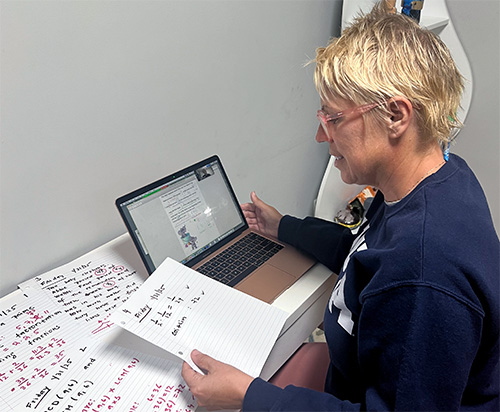

Courtesy of Lara Dolecek

Inspired by something her son said, UCLA math professor Lara Dolecek formed an online class for a dozen elementary school students from a local Palisades school.

Šerifa Dela Cruz, who chairs UCLA’s Economic Crisis Response Team, sorted out emergency financial grants and loans. The priority, she says, was to ensure students did not have to put their education on hold. “We started by making sure they were eating properly,” she recalls.

UCLA faculty, many of whom had also lost their homes, stepped up, including members of the UCLA Olga Radko Endowed Math Circle, which provided free remote math courses for children affected by the fires. Lara Dolecek, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Samueli School of Engineering, who did not lose her own home, taught an online class for a dozen elementary school students from the Calvary Christian School in the Palisades.

“My son inspired me,” she says, “because these kids were spread across the country and needed both the catch-up math and the community. It was inspiring, seeing them return to some normality.”

The Questions That Remain

Last spring, Heather M. Caruso, co-director of UCLA Anderson’s Inclusive Ethics Initiative, hosted two summit meetings — the second of which was 80 present and future civic and industry leaders — to discuss the best ways to restore the communities of Pacific Palisades and Altadena.

The initiative prepared an 18-page discussion paper focused on the Eaton fire, which engulfed Altadena and parts of Pasadena and Sierra Madre. Subsequently, the Anderson Initiative framed three tough questions for the seminars, which will be revisited over the next few years to hold policymakers and builders to account. They are: Who should be involved in shaping the new town? Are historical social inequalities already distorting the rebuilding process in favor of wealthy outsiders, speculators once dubbed carpetbaggers, snapping up lots from those too weary to face rebuilding? And how should different and often conflicting needs and visions about the town be resolved?

“We don’t have all the answers, but asking the big questions at this time is vital because now is the time to think about them, allowing developers and leaders to be held to account,” Caruso says. “Otherwise, we go back to business as usual. And that would be a terrible missed opportunity.”

Courtesy of Kristen Ochoa

Geffen School of Medicine professor Kristen Ochoa, pictured in the Chaney Trail Corridor. She’s been seeing a lot of what is called “solastalgia” — emotional distress caused by the loss of cherished pastoral spaces.

The Natural Cost — and Hope

There is no agreed-upon estimate of how many plants and animals perished in the fires.

Anthony Baniaga, herbarium curator at the UCLA Mathias Botanical Garden, is conducting an inventory of flora losses, looking at the resilient “winners” — manzanita, California lilacs and others with clues in their name, such as the fire poppy, where seeding depends on flame — while others that burned deeper below their crowns to the root stock may be lost forever.

His research, the first full survey covering 1,500 species in the Santa Monica Mountains, will be published at the end of 2026 as both an academic resource — “a snapshot of the health of our mountain flora between Point Mugu and East L.A.” — and a wildflower guide coloring book aimed at elementary and middle school students.

“Up to 90% of a rare species of [the cliff-dwelling succulent] Dudleya was lost in a fire in Agoura Hills,” Baniaga says. “Rare natives are being pushed back to the edge by escapee ornamental grasses such as Pampas and Fountain, whose seeds help carry fires. Black Mustard, also a fire-spreader, benefits from car-released nitrogen, so the more traffic, the higher the risk of fires spread through grasses.”

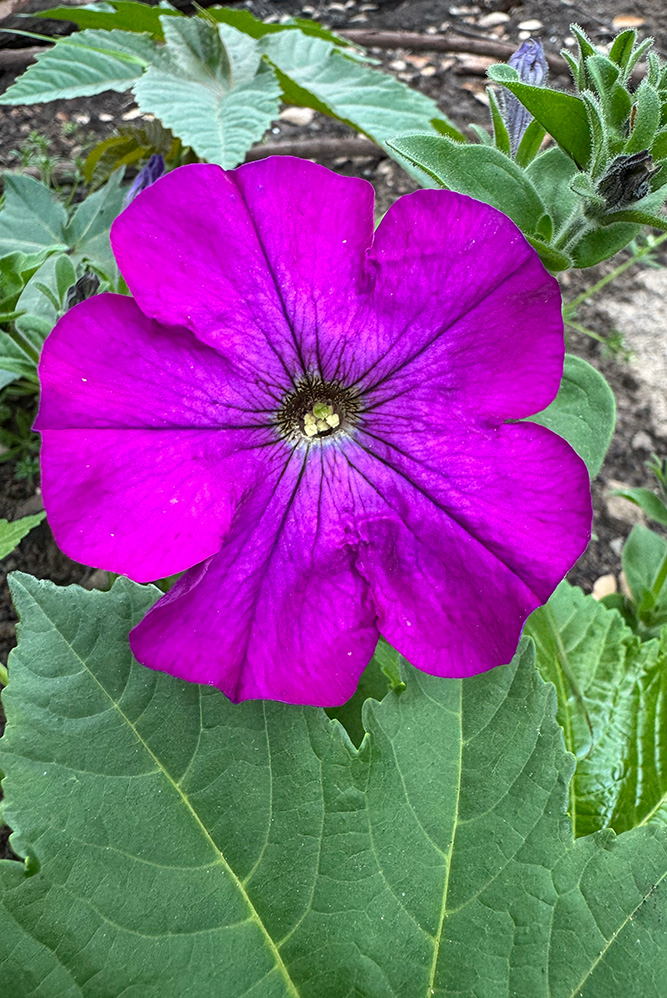

All is not lost. Swipe through a selection of images below showing the return of wildlife growth after the Franklin and Palisades fires.

Courtesy of Morgan Tingley

A petunia flowers in the middle of ash and silt along Rustic Creek

Courtesy of Morgan Tingley

Arroyo Lupine (Lupinus succulentus) blooming after the Franklin fire in Cameron Nature Preserve

Courtesy of Morgan Tingley

A turret bee (Diadasia spp.) sleeps in a Catalina mariposa lily blooming in the Franklin fire

Courtesy of Morgan Tingley

Flowering gumweed (Grindelia spp.) in the Franklin fire

Courtesy of Morgan Tingley

Scarlet pimpernel (Lysimachia arvensis) flowering after the Franklin fire

Courtesy of Graham Montgomery

Previous Next

Nathan Kraft, a professor in the UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, says the big question is how plant life is adjusting to diminishing intervals between urban fires. Woody native species are especially at risk if the “return interval” shrinks to 20 years — particularly if wet years are wetter and dry years drier. “Some natives will not survive that, opening the door to invasive species and changing the landscape,” Kraft warns.

The toll for animals, from woodrats and big cats to peacocks and pets, may be even more profound. In 2020, 17 million vertebrates died in a single Brazilian wildfire, and that was in a wetland — not a chaparral deprived of “measurable” rain for eight months.

During the Eaton fire alone, Pasadena Humane assisted more than 1,500 animals, from pet cats and dogs to chickens and koi and more than 80 different species of injured and/or orphaned wildlife, says Kevin McManus, PR and communications director. Dozens of these animals suffered from smoke inhalation, dehydration and burns.

How many others were affected across Southern California? We may not know the full impact on animals for many years, if at all, and the loss may ultimately be both devastating and incalculable. UCLA researchers are working on such a reckoning as part of the reconstruction of the lost landscapes.

Even as the fires raged, UCLA people were involved in animal rescue. Student volunteers scooped steelhead trout out of ash-threatened Topanga streams, relocating the endangered fish to Santa Barbara. Other Bruins temporarily rehoused confused cats and dogs from Altadena.

Then there were those of the sky. Birds are exceptional indicators of environmental stress and recovery, says Morgan Tingley, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. Some already vulnerable species may have been lost, but up in the hills last spring, Tingley observed groups of Lazuli buntings, a sky-blue bunting that follows fires to feed on newly exposed insects and rapidly reseeding wildflowers.

Captured on a wildlife cam, deer cautiously return to the area in the Cheney Trail Corridor.

There was a stark contrast between the burned higher areas of wilderness, where birds were flocking, and the suburban fire scars, he says, noting, “There is still so much soil and rubble removal, leaving little of the non-native vegetation that Los Angeles homeowners like to plant that house a unique subset of Los Angeles avifauna.”

An entire class of human-interlinked birds may have diminished — at least for now. “Through the science we’re doing, we can learn more about fires in specific areas to better maintain, recover and help coexist with the incredible biodiversity we have in Los Angeles,” Tingley says.

Kristen Ochoa M.P.H. ’11, health sciences associate clinical professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, has seen many friends suffering from the emotional loss of spaces — something experts call “solastalgia,” the distress caused by the destruction of beloved natural spaces.

The summer before the fires, Ochoa set up five motion-activated still and video cameras in Altadena, sharing the images of mountain lions, owls and coyotes on social media. The cameras burned, but there was such a public thirst for a speedy restoration of those glimpses of nature that Ochoa replaced them within a month and began seeing animals coming back to the area.

Read more from UCLA Magazine’s Fall 2025 issue.