Berkeley Rep sat down with Tony Award-winner Jefferson Mays to talk about his one-man performance of “A Christmas Carol,” coming to the Roda Theatre for a limited run this December. Dickens’ timeless tale comes to thrilling new life as Mays plays over 50 roles in a performance he calls “theater in its purest form.” Known for his work across television, film, and theater, Mays is celebrated for his Tony and Drama Desk Award-winning performances on Broadway (“I Am My Own Wife,” “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder”).

“A Christmas Carol” will run Dec. 16–21 at the Berkeley Rep’s Roda Theatre, 2025 Addison St. Buy tickets today online!

This show was co-adapted by Mays, Susan Lyons and Michael Arden and is directed by Barry Edelstein.

“A Christmas Carol: A Ghost Story Told by Jefferson Mays” has gone through several transformations since its debut. Can you tell us how this show was first conceived?

Jefferson Mays: It was one of those odd things: My wife and I were walking our dog through the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, and we ran bang into Matt Shakman, the former artistic director of the Geffen Playhouse. He asked, “Is there anything you’d like to do?” I said, I’ve always imagined doing a one-person version of “A Christmas Carol.” Matt said, “Great, let’s do it.”

So I spent the rest of the year through that summer with my wife, adapting it from Dickens. I just wanted to do this with a table and a chair and nothing else. No soundscape, nothing. I wanted to be the special effect.

In 2018, we had the first showing of it. It was quite different from how I imagined it. We had this extraordinary design team who brought to bear all their theatrical magic on this. I was, I must confess, resistant at first, because it was this phantasmagorical production.

In 2022, it had a limited run on Broadway. After that, Barry Edelstein asked, “Why don’t you come to The Old Globe [in San Diego] and do a version closer to your original vision?” It’s a very intimate in-the-round theater, but the constraints of that space cowed me initially. I wasn’t sure the audience was going to buy it. My back was going to be to two-thirds of them at all times. This is one of the reasons why I’m so excited to come to the Roda. It’s an intimate proscenium theater — Dickens himself refused to do “A Christmas Carol” in any other situation. He didn’t want people to the side or behind him, because I think that constant connection with the audience is really, if not essential, certainly very helpful.

In terms of how it’s changed, well, it’s sort of returned and come back around. I think how it’s going to be at Berkeley Rep in the Roda Theatre is what I originally dreamt of it being. And that’s why I’m so deeply grateful to you and for this opportunity.

What’s brought more into focus in this one-man staging than in more traditional productions?

JM: I’m thrilled to be exploring a version where the emphasis is completely on the storytelling and Dickens’ marvelous, evocative language. But I think it works best as a one-person show because it is in fact a dream, a nightmare in which a person is having this crisis of faith in the middle of the night at Christmas. He is visited by versions of his former self and visits his fearful, imagined future. But it all happens within the head.

And with a one-person version, Dickens’ sense of social outrage comes forward, which is often missing from other adaptations which are more like Christmas pageants. You have the Cratchit family’s Christmas dinner. There’s dancing and singing, and it’s about community. Here, in a one-person staging, you get a really embittered Dickens grappling with the terrible inequities of wealth, education, and health: things that have bedeviled and beset us ever since we came down from the trees and became civilizations. He offers the hope that transformation and change can indeed happen.

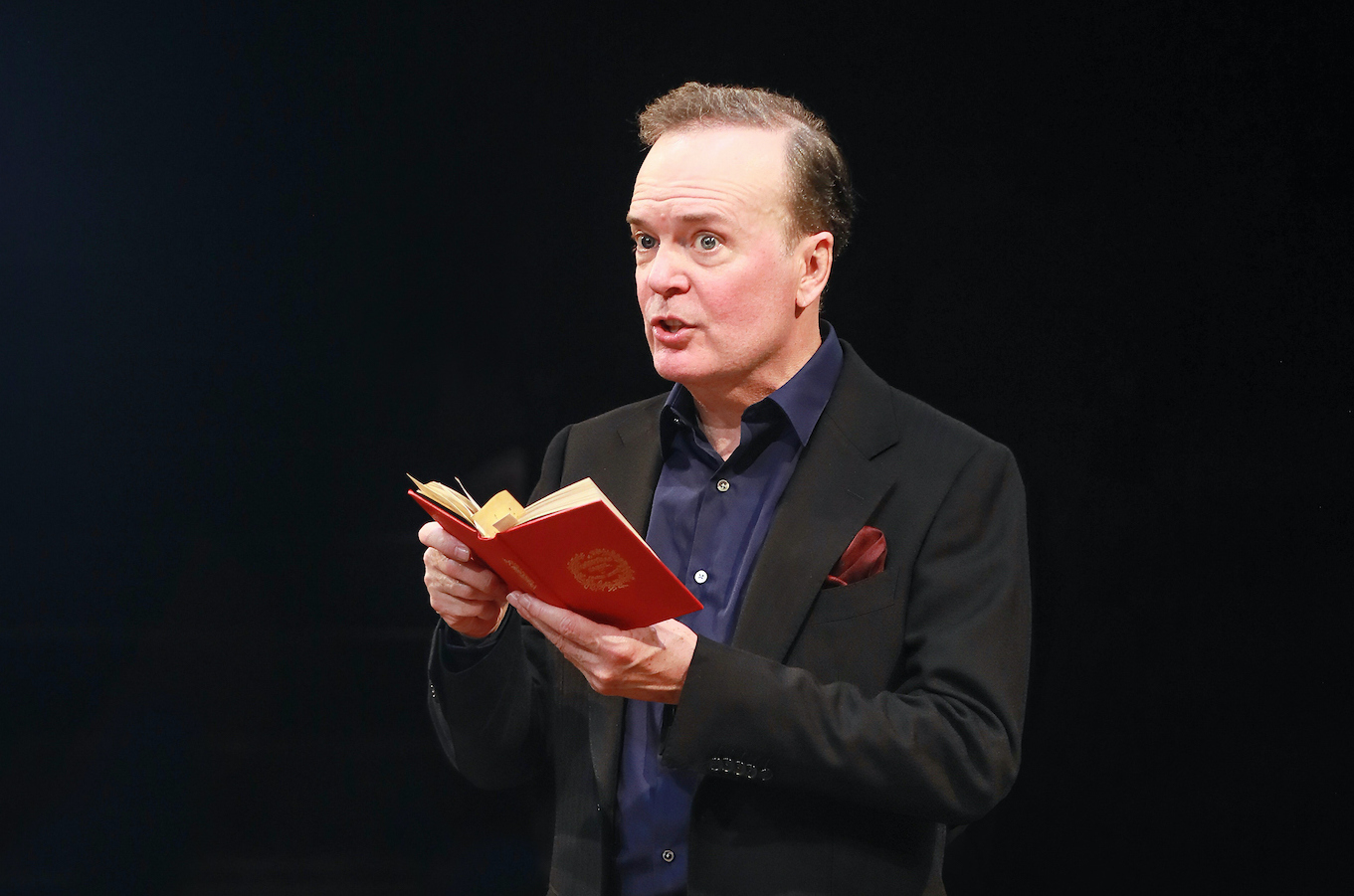

Jefferson Mays performing “A Christmas Carol” at The Old Globe in San Diego. Credit: Jim Cox

Jefferson Mays performing “A Christmas Carol” at The Old Globe in San Diego. Credit: Jim Cox

You play over 50 different characters over the course of the show without costume changes or elaborate sets. Is there something unexpected that’s made possible in this production because of those constraints, either for you or for the audience?

JM: It’s always demoralizing whenever I see any photos from the performance because, on stage, I picture myself in costume — I’m wearing a hoop skirt, or I’m wearing a frock coat and a top hat. I see the foggy, twisting, winding streets of Camden Town. So whenever I see those photos, it’s like, oh, it’s just me in a suit. Not very interesting. There’s always a big disconnect for me.

I want the audience to leave the theater and say I made that tonight. Because it feels to me like such a collaboration. I mean, theater is always that way, but especially in this type of theater, without costume changes or elaborate sets, so much is demanded of the audience. That was the thrilling and surprising thing I came away with from last time at The Old Globe. I’m so thrilled to be able to keep all 600 audience members at the Roda in my eye. I’ll have an individual connection with everyone in the house.

In many ways, it feels… I would use the term “like coming home.” This is how I received literature as a child, when things were read aloud to me. It was my first introduction to theater. Great story, capable performers, and a rapt audience. That’s all you need.

As I’ve grown older, I’m falling more in love with this simplicity. Pure storytelling — the magic and economy of it. You have this text and there’s you and there’s an audience. And the miracle, the wonderful thing that happens is that people just sort of lean towards each other and the performance is something that happens in this strange, empty space between you, in which the audience with their imaginations provides all the special effects and sees a cast of characters and all the atmospherics of Victorian London. It’s theater in its purest form.

“*” indicates required fields