It was Mayor Daniel Lurie’s first town hall to discuss his plan to upzone the low-slung Richmond District, among several other neighborhoods, mostly in the west and north of the city. As the night wore on, the crowd was tough, and the normally even-keeled mayor grew increasingly feisty.

Residents asked repeatedly how he would protect the district’s rent-controlled housing from being demolished and replaced with new, market-rate units, and keep tenants from being displaced. Why couldn’t the mayor’s zoning plan be changed to provide more protections for the local businesses and residents of the Richmond? Surely, there must be alternatives?

Lurie’s response was, essentially, that protections against these kinds of demolitions do exist: The city has one of the strongest rent control protections in the state, he said, and that will continue under the new plan.

Due to these protections, for the past decade when the city’s eastern neighborhoods have already been upzoned, demolition of rent controlled units was “extremely rare.” On average, only seven units of multifamily housing were demolished every year, added Rachael Tanner, director of citywide planning.

And, Lurie said, community feedback had already been taken, and the time for alternatives is over.

To say that the mayor’s office hasn’t listened, he said, “is unfair.”

Any more compromises, Lurie added, and the state could impose the “builder’s remedy,” and completely remove San Francisco’s ability to approve or reject future housing projects within city boundaries.

“If we don’t do it the San Francisco way, it’s going to get done to us the Sacramento way,” he said. The crowd hissed.

“People have said, ‘Sue the state.’ Just sue them and fight,” Lurie said. At this, the audience gave out a loud cheer.

“Other counties have,” Lurie continued. “And they have lost. And builder’s remedy has come in and they have lost funding.”

“We are in an environment where we have a federal government that is not going to be helpful to our city,” he said. “We’re going to have a budget deficit that is worse this coming year. I don’t want to risk losing more state funding.”

Outside the town hall venue, the Internet Archive, members of Planning Association for the Richmond give out flyers and ask the mayor for more tenants and small businesses protection. Photo by Junyao Yang on Nov. 20, 2025.

Outside the town hall venue, the Internet Archive, members of Planning Association for the Richmond give out flyers and ask the mayor for more tenants and small businesses protection. Photo by Junyao Yang on Nov. 20, 2025.

The mayor’s upzoning plan has already been reviewed by state officials to make sure that it was in alignment with state housing goals. Supervisors this week passed what will likely be the plan’s final amendments before it will be voted on by the full Board of Supervisors in December.

As the questions began to repeat themselves, Lurie got increasingly frustrated. The plan has already gone through a lot of changes that incorporated feedback from the community, he said, including an amendment from District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar that will exempt buildings with three or more rent-controlled units from the new zoning plan.

The District 1 Supervisor Connie Chan had proposed amendments to the zoning plan that would have exempted all existing housing, coastal areas, and historic districts from upzoning, and lowered heights on commercial corridors within her district, among other things. But those amendments were tabled by the Land Use and Transportation Committee, and are no longer a part of the current plan.

Chan was not at the town hall, but her aide was, alongside former District 1 Supervisor Sandra Fewer. Fewer is now the vice president of Richmond District Democratic Club, which organized the event and served as its moderator.

Lurie reminded the audience, four times, that the upzoning mostly applies to commercial streets and transit and pedestrian corridors — for 77 percent of the upzoning map, “you can’t go higher than it’s currently zoned.” That, he said, was the result of compromise in the face of community feedback.

The upzoning, in fact, may have a much more limited impact than anticipated. Even in the best case scenario, the mayor’s upzoning plan would lead to only around 14,600 additional units over the next 20 years, according to an October report from the city controller’s office.

The state mandate requires the city to create capacity for 36,000 additional housing units by 2031.

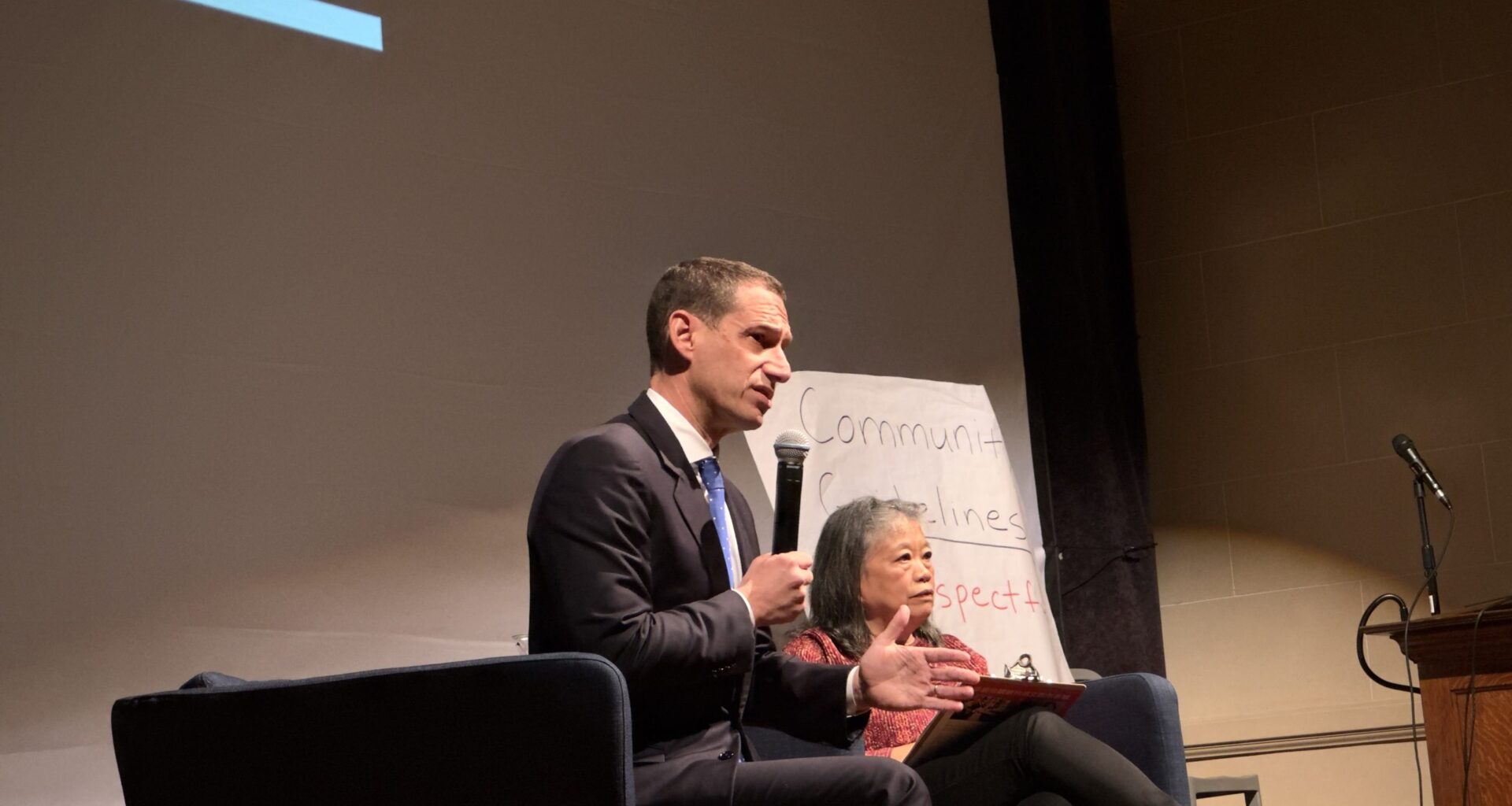

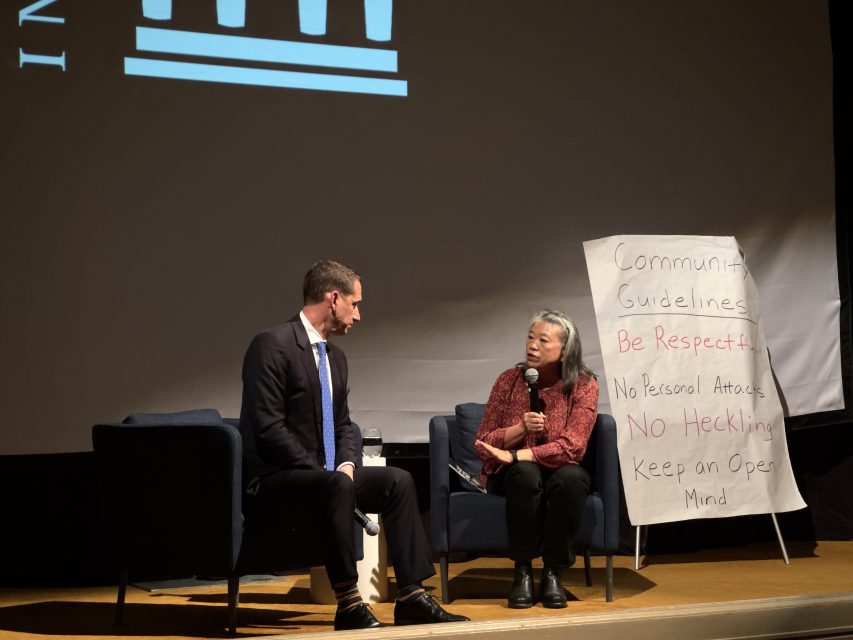

Mayor Daniel Lurie discusses his upzoning plan at a Richmond town hall at the Internet Archive on Nov. 20, 2025. Sandra Fewer, a former District 1 supervisor and the moderator for the event, pressed him about alternatives. Photo by Junyao Yang.

Mayor Daniel Lurie discusses his upzoning plan at a Richmond town hall at the Internet Archive on Nov. 20, 2025. Sandra Fewer, a former District 1 supervisor and the moderator for the event, pressed him about alternatives. Photo by Junyao Yang.

The hour-long town hall at the Internet Archive on Thursday evening ended with a passionate debate between Lurie and Fewer.

Fewer began to press Lurie on the question of alternatives. Seventy-two thousand units of housing had already been approved by the city’s planning commission. Wasn’t there a way to incentivize or mandate developers to build that housing, instead of relying on zoning changes to meet the state housing goals?

“Can we submit an alternate plan?” Fewer asked.

“The plan is being altered,” Lurie responded, referring to the amendments, passed by the Land Use and Transportation Commission on Monday.

“I meant an alternate plan that includes a plan to either incentivize or mandate the 72,000 units that could break ground tomorrow,” Fewer said. “How can we allow them to hold our city — which is only 49 square miles — hostage until they are ready to make their adequate profit?”

The city should “put our foot down,” Fewer added, to mandate developers to build those approved housing units, and stop granting extensions to stall development. Sure, interest rates are high and so are construction costs, but if they need financing to start development, the city could help with that. “If they refuse, why are we not invoking eminent domain?” Fewer said, as the crowd began to cheer, loudly.

“Who’s gonna pay them?” Lurie said quietly. “We have the money?”

The mayor’s upzoning plan has already taken the units in the city’s housing pipeline into consideration, added Tanner, the planning director. The city is currently incentivizing developers by expediting permitting,” Tanner added. “But it’s difficult to compel someone to do something, particularly if it requires them to spend money.”

At the end of the town hall, Lurie seemed to have heard enough. “To say we have not worked hand in hand with supervisors and community members, that we haven’t made adjustments, is just not true,” he said.

“The underlying question here is,” Fewer pressed again. “Can we have an alternate plan instead of …” At this, Lurie interrupted her.

“Actually what’s gonna happen is … there’s gonna be a vote at the Board of Supervisors. We are gonna see. And the plan is going to be submitted. It’s gone through the whole democratic process,” Lurie said.

“And I just want to remind everybody, there are people that are really excited about this plan.” That does not, he added, have to include the people present tonight. “But there are a lot of people.”