San Francisco is on the verge of passing its most meaningful housing legislation in nearly 50 years. Before breaking for the winter holidays, the city’s supervisors must vote on a redesign of the city’s housing map to allow taller, denser buildings, mostly in western and northern neighborhoods, or else far more drastic options could kick in.

In recent weeks, supervisors have wrangled over amendments to the basic plan, which comes from Mayor Daniel Lurie and city planners. Many of the amendments aim to protect renters and small businesses.

There are still contentious votes to come. But people on most sides agree that the city needs more affordable housing.

Easy to say. Easy to demand. But very hard to do. Subsidized housing is subject to the same costs of labor and materials as market-rate construction and can cost up to $1 million per unit in San Francisco.

Sup. Myrna Melgar has an idea for a fresh source of funding that piggybacks on the new plan for taller, denser neighborhoods: The more new homes sold or built on San Francisco’s west side, the more money would flow toward affordable housing there — where it’s most needed.

The western districts — 1, 4, and 7 – contain about 23 percent of SF’s homes, according to city planners, but very few are subsidized to be affordable.

Melgar’s both a clever idea and one fraught with the problem of all San Francisco housing politics: you need to build market-rate homes to get the subsidized ones.

Tapping into taxes

The mayor’s new housing plan, dubbed the Family Zoning Plan, is supposed to make room for tens of thousands of new homes, more than half of them affordable. But it doesn’t come with funding for those homes or instructions on how to find it.

Backers say that was always the plan. Upzoning simply creates room — or “capacity” — for more construction, which in turn makes more construction (including affordable homes) possible.

Critics say it’s a bait-and-switch. “Where’s the funding?” says Fred Sherburn-Zimmer, director of the Housing Rights Committee of SF. (She also says she’s for “affordable housing on every [available] lot.”)

Even if construction costs drop in ways that range from highly unlikely (SF backs off its promise to labor unions) to who-the-heck-knows (the Trump tariffs disappear and inflation stays tame), the city must find tens of billions of dollars.

Melgar is the chair of the city’s key Land Use and Transportation Committee and has been both an evangelist and a shepherd for the Family Zoning Plan. To appease its critics, she is also pushing separately for an affordable housing fund for the west side. (Her District 7 is one of three that could be in the zone.)

Two months ago, the board voted 10-1 in support of her proposal. The next step is for three city agencies to fill in details. (There are already delays; they missed a Nov. 1 deadline to report back to Melgar.)

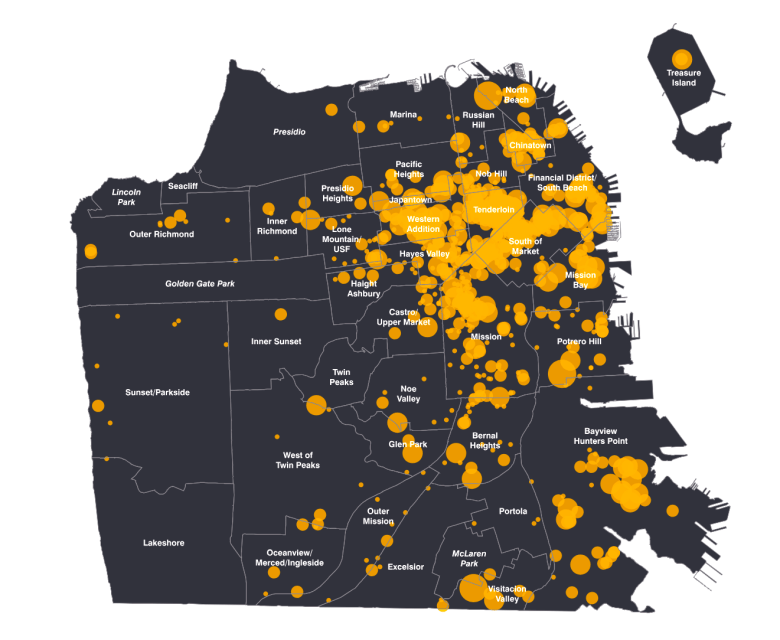

San Francisco’s affordable housing locations are concentrated almost entirely in the city’s eastern half. This map is from 2019, but not much has changed since then. (SFPlanning and MOHCD)

San Francisco’s affordable housing locations are concentrated almost entirely in the city’s eastern half. This map is from 2019, but not much has changed since then. (SFPlanning and MOHCD)

Even if it comes to fruition, it would not solve the affordable funding problem. But unlike other ideas, it would lean on a well-known and renewable source of revenue: San Francisco property taxes. Instead of adding a new tax, it would tap into existing ones.

Here’s how it would work:

* First, the plan would map out a new tax district. The boundaries aren’t yet set, but it could encompass much of San Francisco’s west side, where the Family Zoning Plan will raise allowable heights and increase housing density.

* When the city reassesses the value of a property within the district, the dollar difference between the old and new property tax values would flow into the affordable housing fund. Reassessments happen for several reasons: a new structure goes up, an existing home gets a renovation or a backyard unit, or a property changes owners.

* So if a single-family home on 34th Avenue, assessed at $700,000 in 2010, sells for $1.5 million, the difference in the old and new property taxes — about $8,000 a year — would go to the affordable housing fund. About $7,000 would still go to SF’s general fund.

Until the boundaries are drawn, it’s impossible to estimate how much revenue such an instrument could eventually raise. The assessor-recorder’s office says it could not immediately calculate those districts’ share of the city’s property tax.

The proposal would treat affordable housing like infrastructure, and across a much larger area. ‘Nobody’s ever done it for housing before.’

sup. myrna melgar

But one potential advantage is that the plan could extract funds for affordable housing from small apartment buildings and even single-family homes.

That’s not possible today. In the current “inclusionary system,” only new buildings with 10 units or more must either include some subsidized apartments, or the developers must pay into a citywide fund to build them elsewhere.

Sup. Stephen Sherrill voted to advance Melgar’s proposal and suggests tax-related ideas like it, which produce a “steady ongoing revenue stream,” could replace one-time developer fees. “The City should take a hard look at where we get the greatest return for every dollar,” Sherrill says via email.

Homes as infrastructure

Special tax districts for infrastructure are nothing new. SF has mostly used them to cover the costs of sewers, streets, and utilities within tight boundaries, like at the half-finished Pier 70 development. But Melgar’s proposal would treat affordable housing like infrastructure, and across a much larger area. “Nobody’s ever done it for housing before,” Melgar tells The Frisc.

Former supervisor Aaron Peskin tried something similar last year, not with taxes but a kind of bond that typically covers infrastructure costs.

Peskin’s “missing middle” bonds — named so because the subsidy level would target middle-income, not low-income, residents — have yet to entice any developers, according to Anne Stanley, spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD).

Melgar says her tax plan and the Peskin bonds are “apples and oranges,” although they do both consider homes as infrastructure. They have something else in common. Melgar acknowledges that housing could take years to blossom under her plan.

First of all, it’s still just a proposal, and a delayed one at that. But assuming the agencies tasked with filling in details (the Controller’s Office, Office of Economic Workforce Development, Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development) craft something the board approves next year, the funds will more likely arrive in a steady trickle, not a near-future flood.

The city’s chief economist Ted Egan recently underscored this risk. Egan projected that the Family Zoning Plan would not spur as much new housing as backers have hoped.

Critics of the plan used Egan’s assessment to blast the plan’s market-rate focus. But its backers say boosting capacity is needed to create more incentives. “A tough market hurts, but we can’t just throw our hands up and say nothing will happen,” says Jane Natoli, organizing director for YIMBY Action.

The only opponent of Melgar’s proposal was District 1 Sup. Connie Chan, who said in September that it would likely take decades to produce significant income. She also objected to it only focusing on western neighborhoods. (It would include Chan’s Richmond District.) Chan has also recently fought to roll back the Family Zoning Plan with several amendments that Melgar voted down.

@myrnamelgard7.bsky.social takes on Chan’s “pitting west side vs east side” comment (award for top demagoguery of the day). Melgar: SF *downzoned* the west side in the 70s. Racism/segregation contributed to that prohibition of multifamily housing and concentrated development on the east side.

— The Frisc (@thefrisc.bsky.social) 2025-11-18T00:50:41.198Z

Instead of Melgar’s proposal, Chan encouraged lawmakers to focus on affordable housing bonds. Melgar pointed out that the tax proposal doesn’t preclude tapping into bonds as well.

She also could have mentioned that bonds present SF with a similar problem: They’re only one small piece of the funding puzzle.

A patchwork future

A massive federal plan to subsidize millions of new homes across the Bay Area and state was something in play for supporters of a Kamala Harris presidency. But the scenario much harder to imagine these days. Short of that, funding for affordable homes will continue through a patchwork of sources, disbursing drips and drabs that come nowhere close to solving the crisis in the time frame most observers would find acceptable.

“Development is happening,” says MOHCD’s Stanley. But she acknowledges “the challenges we’re facing in funding and delivering affordable housing are closely tied to broader market conditions” mostly out of the city’s hands.

SF voters reliably approve funds — typically bonds in the hundreds of millions of dollars — every few years. But alone they’re not at the scale needed to move the needle. The most recent, 2024’s Prop A, would build about 1,500 units.

As Chan has noted, going bigger is possible. A state bond will likely be on next year’s ballot. Still, $10 billion would only build 35,000 homes statewide, and the politics are no slam-dunk; an attempt at a $20 billion megabond for the entire Bay Area couldn’t even get to the ballot in 2024.

SF policymakers keep trying a range of ideas, like easier office-to-housing conversion and Peskin’s missing middle bonds, but they have seen scant returns.

Melgar’s plan, if it works, would be yet another source, designed to dole out funds at a marathon pace, not a sprint.

More from The Frisc…