The recent passage of a countywide sales tax measure is expected to soften federal funding cuts to Silicon Valley’s largest public hospital system. But it won’t avoid cuts entirely — and places like Santa Clara County’s premier cancer treatment center could still be affected.

It’s estimated that roughly 18% of all Santa Clara County cancer patients will be admitted to the Sobrato Cancer Center, located at Valley Medical Center in San Jose. The state-of-the-art facility doesn’t turn anyone away, be it low-income people on public health plans or those who lost their insurance after starting treatment at a private hospital. Early diagnoses, infusion services, chemotherapy and multi-disciplinary care help keep these patients out of already-full emergency rooms.

But that safety net is at risk of fraying.

County doctors and patients are looking at massive hospital cuts — and possible closures — resulting from H.R. 1, the federal “One Big Beautiful Bill” that cut $1 trillion from Medicaid, the public health insurance program known locally as Medi-Cal. Reimbursements under Medi-Cal provide the largest source of funding for Santa Clara County hospitals.

The center routinely reaches capacity, seeing about 40,000 patient visits every year — a little under 7,000 unique patients.

“If there are going to be cuts, patients are going to have to wait longer, and that is actually going to impact their prognosis. That’s the hard truth,” Nam Cho, a radiation oncologist and medical director of the Sobrato Cancer Center, told San José Spotlight. “The worst thing that we have to say to a patient is, ‘I don’t have a space for you today.’ But that could absolutely become the rule instead of the exception.”

At the 11th hour, county leaders put a five-eighths-cent sales tax increase known as Measure A on the Nov. 4 special election ballot. It passed with 57% voter approval, but some officials have competing ideas on how the money would be used. A proposal to allocate the dollars fully toward the hospital system has caused a rift among law enforcement interests who backed the measure thinking they would see some of the revenue — and District Attorney Jeff Rosen has threatened an investigation.

“The approval of Measure A funding by the people in Santa Clara County will play a significant role in maintaining high-level cancer treatment and other services lines for our patients,” Cho said. “Unfortunately, our health care system still faces difficult financial challenges moving forward. Nonetheless, we will continue doing everything possible to deliver the best possible care for our community.”

County leaders have said Measure A alone won’t solve the county budget issues caused by the federal cuts. While the measure is expected to generate $330 million annually, that only covers a third of the anticipated cuts.

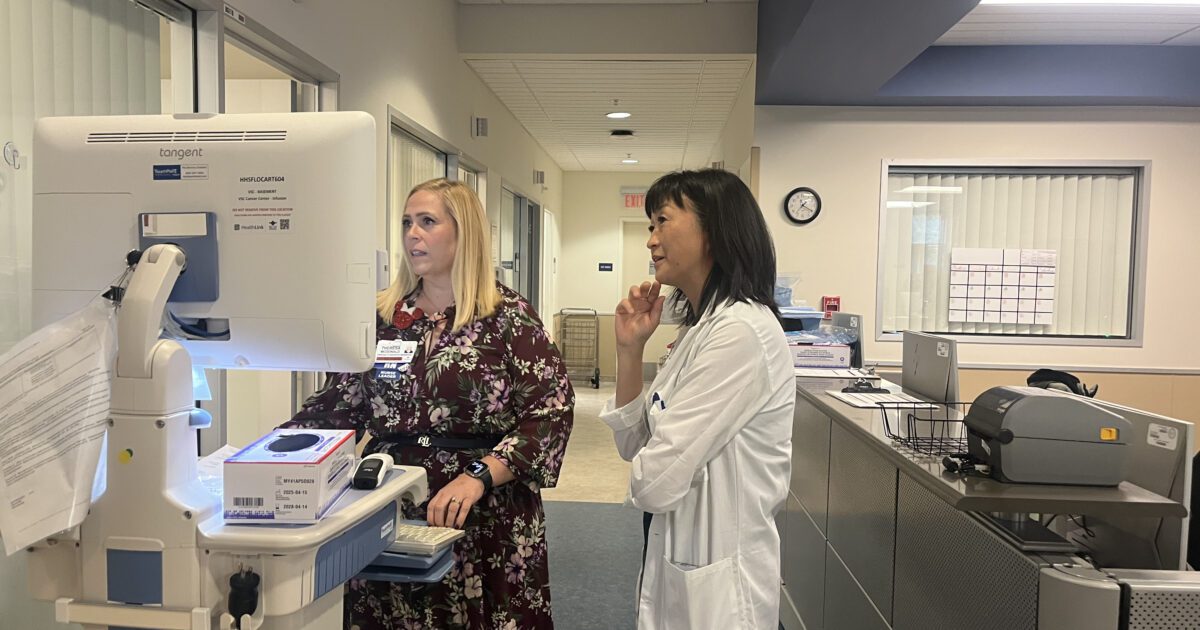

The Sobrato Cancer Center doesn’t just care for cancer patients — but also other diseases that can be treated through infusions. This has contributed to the center’s capacity issues. Photo by Brandon Pho.

The Sobrato Cancer Center doesn’t just care for cancer patients — but also other diseases that can be treated through infusions. This has contributed to the center’s capacity issues. Photo by Brandon Pho.

At capacity

Medical advancements have converted cancer from a death sentence to a condition people might live with for a protracted period of time. That’s largely due to early detection services that places such as the Sobrato Cancer Center provide.

“That’s the other piece we worry very much about with these cuts,” Cho said. “We keep hitting our capacity and having to figure out other ways of increasing capacity with what we have because patients are living longer and still needing treatment.”

The center doesn’t just treat cancer patients — it also handles treatments for rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases. Theresa McDonald, an assistant nurse manager overseeing the infusion center at Sobrato, said new biologic drugs have come out in the last decade that work wonders, but the treatments still take up space.

McDonald said the center is working to address that through offering more infusion chairs at other facilities. Another infusion center operates inside the county-run St. Louis Regional Hospital in Gilroy, which recently expanded from two infusion chairs to four.

Not only does it allow patients to avoid long commute times in favor of care closer to home, but the expansion offers other ancillary services such as lab work and dressing changes. The expansion of access and capacity in South County has allowed for capacity to free up at Valley Medical Center.

“A cancer patient often can have, no joke, five different appointments in a week,” McDonald told San José Spotlight. “So even increasing just by the two chairs, it might seem minimal, but it’s actually huge.”

Santa Clara County’s public hospital system became California’s second largest in 2019 after the county bought three financially-struggling hospitals — O’Connor Hospital in San Jose, St. Louise Regional Hospital in Gilroy and De Paul Health Center in Morgan Hill. The facilities were at risk of closing and turning stretches of the county into health deserts.

Last year, the county also bought Regional Medical Center in East San Jose after corporate owner HCA Healthcare made a set of profit-driven cuts to lifesaving care. The county has since restored services that were lost under private providers, such as East San Jose’s maternity ward.

Thomas Powell-Demeuth and his wife, Makai, have been coming to the Sobrato Cancer Center at Valley Medical Center for 11 years. Photo by Brandon Pho.

Thomas Powell-Demeuth and his wife, Makai, have been coming to the Sobrato Cancer Center at Valley Medical Center for 11 years. Photo by Brandon Pho.

A human toll

Thomas Powell-Demeuth found himself in the Valley Medical Center emergency room in 2015 after falling while reaching for toothpaste in his medicine cabinet and hearing troubling popping noises, which turned out to be his bones. He was later diagnosed with multiple myeloma, which are cancerous plasma cells built up in bone marrow. He lived in San Jose at the time, but when he later relocated to Santa Cruz to be with his partner he opted to stick with his care team at the Sobrato Cancer Center.

“I’m absolutely stubborn about my care team here,” he told San José Spotlight. “I would somehow manage to fly from the other side of the country to be here for my care team if I could.”

Powell-Demeuth needed reconstructive surgery on his leg. He had lesions over about 84% of his body, with broken ribs and fractured and compacted vertebrae due to the multiple myeloma. He said his team got him into good enough shape in 2016 to go to Stanford Hospital for his first stem cell transplant. He went into remission for a few years and married his partner. One of the nurses from his care team attended the wedding.

But he reentered treatment at Sobrato when signs pointed to the cancer returning. In 2022, after a lengthy treatment session, he went back into Stanford for a second stem cell transplant. He’s been doing maintenance treatment at Sobrato ever since. Come January, he will have been a Valley Medical Center patient for 11 years. Powell-Demeuth said the threat of hospital cuts is “disappointing” and “frightening.” He recalled a survivor picnic he attended at Stanford, where he met a cancer patient under 10 years old and discussed her diagnosis.

Powell-Demeuth said the threat of hospital cuts is “disappointing” and “frightening.” He recalled a survivor picnic he attended at Stanford, where he met a cancer patient under 10 years old and discussed her diagnosis.

“When I heard about this budget situation — I mean, that absolutely brought me back to that moment, looking at that little girl, seeing how hopeful she was,” he said. “Then all of a sudden in the back of my mind, I was like, ‘What’s going through her parents mind?’”

Powell-Demeuth said cancer treatment hinges on issues as simple as proper equipment.

“I mean, something as simple as an office chair that’s falling apart, or machines,” he said.

It also depends on people.

“I definitely worry about the care team here,” he added.