The morning of Jan. 17, 2025, federal prosecutors filed into a windowless room at the San Francisco federal building and lined up solemnly behind the podium.

They were about to announce a bombshell political corruption case. Hours earlier they had unsealed an indictment charging Oakland’s newly recalled mayor Sheng Thao, her romantic partner Andre Jones, and two local recycling moguls, David and Andy Duong, with orchestrating an elaborate bribery scheme.

Meanwhile, the man who appears to be the FBI’s key informant in the case was on vacation, barefoot on a boat flying the Greek flag from its stern. He smiled as the sun set over the sea behind him.

“No stress, just vibes,” he captioned photos he posted on X.

Mario Juarez, a well-known Fruitvale businessman, is widely believed to be the person federal prosecutors referred to in the indictment as “Co-conspirator 1.” Identified by the feds as a local businessman, an active member of the local political community, a cofounder of a housing company with the Duongs, and the figure behind negative mailers targeting Thao’s opponents in the race for mayor, Juarez is the only person who ticks every box.

According to the government, Co-conspirator 1 and the Duongs bribed Thao and Jones in pursuit of millions of dollars in city contracts.

The indictment includes evidence like text messages sent by Co-conspirator 1 to Andy Duong, seemingly admitting to fraud. “So we may go to jail… but we are $100 million dollars richer,” he wrote in one exchange.

But Juarez does not appear poised to do time.

Instead, it seems he may have avoided repercussions by feeding the government a trove of information it used to bring charges against Thao, Jones, and the Duongs, in an indictment that leans heavily on statements of Co-conspirator 1. While his former associates were court-ordered not to travel outside Northern California while they await trial, Juarez appears to be freely moving about.

In October, the attorneys for David Duong filed a motion in the federal corruption case, trying to get the evidence against him tossed out. The government’s main source, his lawyers argued, is “a known fraudster with a grudge.”

Duong’s lawyers note in the filing that Co-conspirator 1 has been a party to some 33 lawsuits, in which he’s been accused repeatedly of cheating people, companies, investors, and government agencies of at least several hundred thousand dollars.

Just a few years earlier, Duong had trusted Juarez enough to launch a business with him, promising to invest $1 million in a company peddling shipping container homes to local governments.

It won’t be the first time Juarez has evaded consequences after being linked to claims of wrongdoing. In numerous cases over the past two decades, Juarez has been accused of fraud or embezzlement, only to bounce back and pursue the next venture. He has gotten into business with reputable companies and prominent figures until many of these deals ended in explosive falling-outs. Then came messy lawsuits, and in a few cases, criminal charges. But Juarez has managed, so far, to avoid any criminal convictions, and despite some hefty judgements, he’s always been able to move on, strike new deals, and cultivate new investors.

The Oaklandside reviewed 27 civil lawsuits involving Juarez, mostly in Alameda County Superior Court, over the past two decades — many of which read like the script of a bingeable podcast or television miniseries.

There’s the time he got hired to represent an iconic Mexican rock band — and then allegedly paid to promote them with someone else’s credit card. Or the time he lined up a home loan for a woman on behalf of a nonprofit he helped run — and then allegedly pocketed her payments himself. Or the case where his landlord claimed Juarez built a “high-end residence” in an Oakland commercial property; Juarez claimed it was a showroom, but moved his family in.

Many of the details in the suits closely match those cited by the Duongs’ lawyers in their motion, further corroborating Juarez’s identity as Co-conspirator 1.

Juarez posted vacation pictures to X the same week the federal government announced the indictment against Thao and the Duongs.

We also examined records for Juarez’s two bankruptcies, enforcement records that led him to surrender his real estate license, and records related to three criminal prosecutions of Juarez for fraud, forgery, or embezzlement. It’s possible there are more cases in other courts.

What’s most striking about the Juarez story is that he maintained close ties for much of this period with some of the East Bay’s most influential political players, including Rob Bonta, now the state attorney general; his wife Mia, now a member of the state Assembly; state Assemblymember Sandre Swanson; and Kathy Neal, a port commissioner and former Oakland first lady. Some, even after multiple fraud lawsuits had been filed against Juarez, intervened to vouch for his business efforts, including Rob Bonta in 2014.

Juarez “figured out he could make political connections and people would hold their noses,” as one party activist told us.

Bonta was recently dragged into more news about the FBI’s case after a letter Juarez sent the attorney general last year surfaced. In the note, Juarez told Bonta that video of him existed in a “compromising position,” and that this video was in Andy Duong’s possession. Bonta recently called this “absolutely not true.”

Most political figures declined to comment for this story. Juarez did not respond to multiple interview requests. But in response to several of the lawsuits, Juarez has maintained that he’s been wrongfully accused — sometimes asserting that his accusers are actually the ones in the wrong.

The debt collector

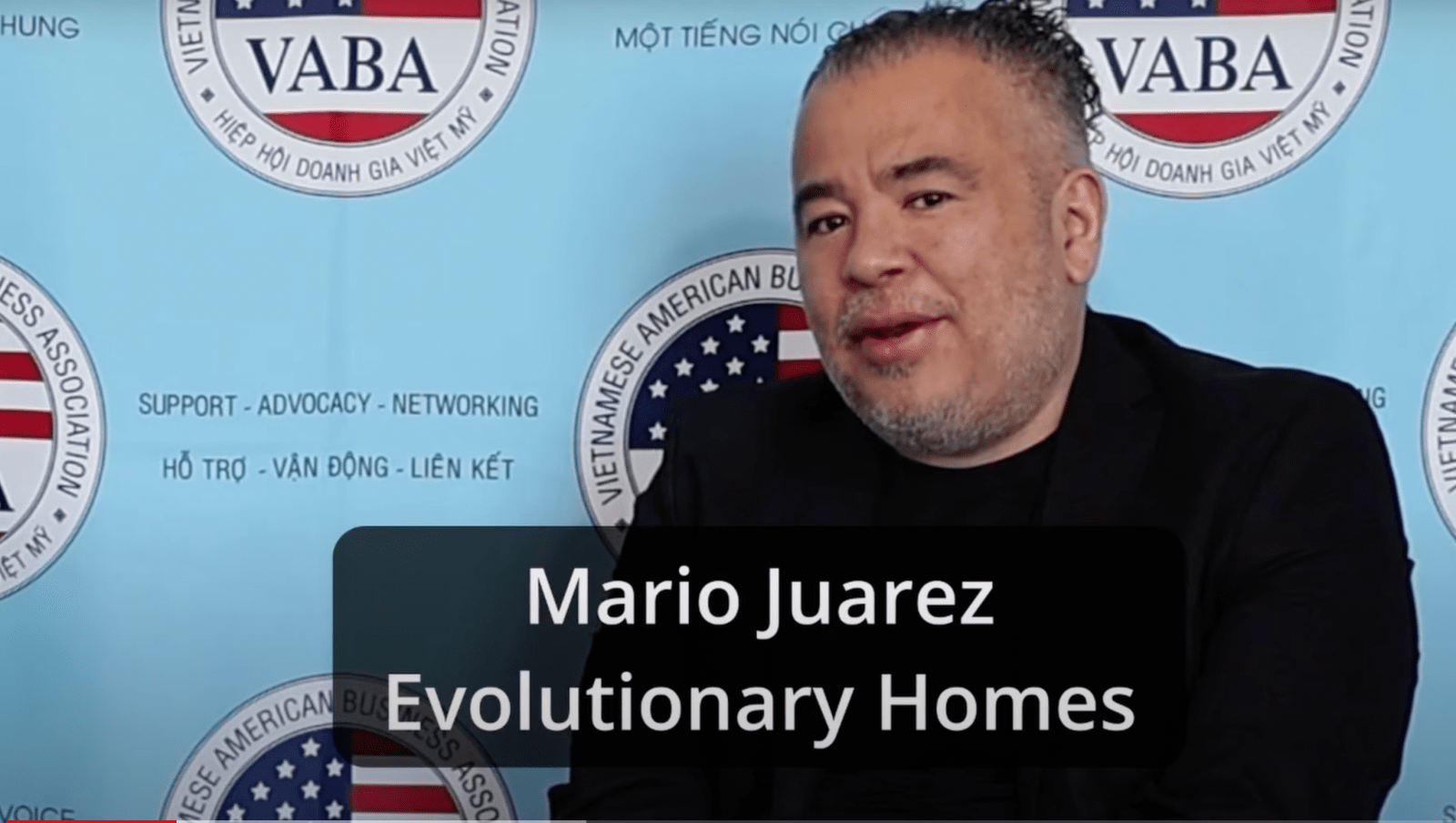

A screenshot of an interview with Mario Juarez from a video posted by the Vietnamese American Business Association, a networking group run by the Duong family. Credit: courtesy of VABA

A screenshot of an interview with Mario Juarez from a video posted by the Vietnamese American Business Association, a networking group run by the Duong family. Credit: courtesy of VABA

Born in Honduras in 1977, Mario Juarez immigrated to the United States as a child and grew up in Oakland, ultimately graduating from Fremont High School. In a recent blog post, Juarez described the Oakland of his childhood as a difficult one, where his community was treated as “an afterthought,” gang members were killing each other, and leaders failed to act. “I didn’t learn about injustice from a textbook,” he wrote. “I lived it.”

His childhood was also scarred by a horrible crime. Juarez’s mother had enrolled him in the Boy Scouts, hoping he’d find a positive male role model. But his troop leader, Jorge Francisco Paz, betrayed that trust, molesting him and other boys.

“Juarez was ashamed and kept it a secret” for a time, Robert Gammon wrote in a 2008 East Bay Express story. “But then, three years later in 1993, the teenager found the courage to tell police what Paz had done.” Juarez testified in court against a plea deal prosecutors sought for his abuser. Paz was ultimately sentenced to 14 years in prison, and a lawsuit Juarez filed later against Paz and the Boy Scouts helped lead to a reckoning in the organization.

By his very early 20s, Juarez was already an entrepreneur, one drawn to a combative corner of the economy: the collections industry.

He joined forces with a business partner, Gergely Csaszar, to set up a company in Oakland, American Judgements Corporation. The business model was simple. Clients would hire the company to collect judgments won in lawsuits and other legal proceedings. Juarez and Csaszar got to keep a small percentage of anything they could collect.

In April 2002, Juarez was thrust into the first of what would become many messy disputes with business partners. Csaszer filed suit, accusing Juarez of “converting” their company’s assets — client lists, computers, websites, and more — to his own use by secretly setting up a rival company. Juarez had also used company funds for personal gain, Csaszer claimed.

Juarez denied the allegations and argued the case couldn’t go any further since he’d hit a tough spot financially. Juarez, at age 24, filed for bankruptcy.

Csaszer’s case against Juarez doesn’t appear to have gone anywhere, according to court records. Attempts to contact Csaszer and his attorney for this story were unsuccessful. The attorney who represented Juarez is deceased.

Juarez’s bankruptcy case dragged on for another five years, during which Juarez sometimes failed to make planned payments to creditors, resulting in notices of default in 2003 and 2004, according to the case docket.

Former Mayor Sheng Thao leaves the federal courthouse in Oakland after a hearing in the corruption case. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Former Mayor Sheng Thao leaves the federal courthouse in Oakland after a hearing in the corruption case. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

In May 2002, just weeks after filing for bankruptcy, Juarez set up a new debt collection company, The Judicial Group. The following month, Juarez scored a big deal — a contract with the city of Oakland. The Judicial Group was given the right to contact people and businesses who owed the city money, negotiate with them about repayment, and collect. Juarez got to keep 49% whatever payments were recovered, or $14,999, whichever was less.

It’s unclear whether any city officials knew in June 2002, when Oakland hired Juarez’s company, about the red flags — the lawsuit his former business partner had filed against him two months before, or his bankruptcy. But the city’s contract with Juarez would prove to be one of the first of many cases where prominent people and government agencies trusted a man with who already had a record of financial chaos and conflict that could have given them pause.

Two years into the city contract, Juarez began failing to follow its terms, according to a lawsuit the city attorney, then John Russo, filed against Juarez and The Judicial Group. The company, the city claimed, cheated Oakland “by failing to accurately report the amount of judgments that it collected under the agreement, and by failing to disburse to plaintiff, 51% of the judgments.” Juarez also failed to return roughly $15,000 in a mistaken overpayment, the city said, and failed to maintain business records. Russo even claimed Juarez had destroyed company records “with the deliberate intent to hinder, delay, and defraud” the city of Oakland.

Juarez’s attorney, Michael Cardoza, denied the charges. But in 2007, Juarez and the city settled, with Juarez paying Oakland $31,000.

Other clients were soon facing similar frustrations over Juarez’s debt collection businesses.

In June 2006, Juarez was hit with another lawsuit, in which two clients claimed that he and his collections company “kept for their own unjust enrichment” $108,000 that was owed them after winning the sum from a negligent dentist.

Then another lawsuit landed, this time from an Oakland-based office equipment company, accusing Juarez of collecting money from at least two judgment debtors and failing to account for the money and to pay the company. The company and Juarez eventually reached a nondisclosed settlement.

The $108,000 collections suit dragged on until 2010 when Juarez was ordered by a judge to pay $94,000.

Juarez has yet to pay.

Last year, Todd Haines, who told The Oaklandside he was hired to try to collect the money from Juarez, filed papers in state court showing Juarez still owes $164,000.

As his collections work began to hit the skids, Juarez was already laying the groundwork for a new career — in real estate. He obtained his broker’s license in 2004, and was soon building out a portfolio of work, serving as an agent for homebuyers and buying and leasing commercial real estate. Many of the deals would spark their own lawsuits. But they would also allow him to offer critical favors to influential figures in the Democratic Party.

Juarez enters politics

Juarez’s legal troubles began to garner public attention in the late 2000s, when he decided to jump into politics.

In 2008, Juarez announced he was running for Oakland City Council. He aimed to unseat Ignacio De La Fuente, the longtime representative for Fruitvale, who was fresh off a failed bid for mayor. Juarez had previously supported De La Fuente, including in his unsuccessful mayoral bid, but the 2008 campaign got ugly.

In media interviews, Juarez claimed that Russo, the city attorney, had sued him only because he was good friends with De La Fuente, and the two men wanted to stop him from running for office. Russo called Juarez’s claim “absurd”; De La Fuente called him “a God-damned opportunist.”

De La Fuente described Juarez to The Oaklandside more recently as a “bullshitter” and “con guy” who had a bad name in Fruitvale.

Around the time Juarez was running for his seat, De La Fuente said, community members independently contacted his City Council office about Juarez’s business activities. “I heard from many people who came to my office to complain,” he said.

Former Councilmember Ignacio De La Fuente at a mayoral forum in 2022. Juarez ran against him for council in 2008. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

Former Councilmember Ignacio De La Fuente at a mayoral forum in 2022. Juarez ran against him for council in 2008. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

The 2008 campaign surfaced other allegations. Juarez’s ex-wife, Araceli Lopez, accused him in court documents of repeatedly hitting their son, the East Bay Express reported. A court-appointed counselor recommended that Juarez stay away from his son for a period of time, and a judge ordered him to stop using corporal punishment.

Juarez lost the 2008 election — but he gained some powerful supporters.

As a candidate, Juarez picked up support from SEIU 1021, IFPTE Local 21, and the Oakland Education Association, unions that represent thousands of city workers. He also received an endorsement from the Alameda County Democratic Party. And the businesswoman Kathy Neal signed on as his campaign manager. Neal was a politically connected consultant who had served on the port commission and had been married to Elihu Harris when he was Oakland’s mayor.

Neal told The Oaklandside she met Juarez through a mutual friend and wasn’t yet aware, when she agreed to be his campaign manager, of just how many lawsuits were dogging Juarez.

When De La Fuente decided not to run again for the District 5 council seat in 2012, Juarez ran but lost to Noel Gallo, who still holds the seat. But Juarez picked up thousands of dollars in contributions, according to campaign finance filings, including from unions, the Oakland Chamber of Commerce, and influential politicos, including Harris; Rob Bonta, who was then San Francisco’s deputy city attorney; Shawn Wilson, who was then chief of staff to State Assemblymember Nate Miley; Jim Odie and Vinnie Bacon, who would go on to become city councilmembers in Alameda and Fremont, respectively; and state Assemblymember Sandre Swanson.

Unable to crack the Oakland City Council, Juarez set his sights on the Alameda County Democratic Central Committee, an elected body that endorses local candidates and sends resources their way. Neal again served as his guide, showing him how to campaign for a seat on the committee.

Juarez won the seat in 2012. He quickly became an inveterate networker, according to those who served with him on the committee.

“As soon as he got on the central committee, he tried to make his real estate office the center of activity for Democrats,” said Pamela Drake, who was also elected to the board in 2012. “He’d have meetings there, provide food and drink, be magnanimous about what he’d offer.”

“He always had money, so he helped raise money for people’s campaigns,” said Margarita Lacabe, a member of the central committee from 2010 to 2020. “He allowed his office to be a place for people to run staff from. He introduced people to others. He played the political game.”

According to Lacabe, Juarez became close to important people on the committee — including the Bontas.

In a declaration filed in state court last December — part of a motion filed by then-DA Pamela Price, objecting to Juarez’s attempts to have a criminal case against him dropped — Lacabe described Juarez and Rob Bonta as “close political allies.” She said the pair were “consummate politicians who worked to befriend politically powerful and resourced people.”

After Bonta was elected to the State Assembly in 2012, Juarez continued to support him by helping him coordinate votes and nominations to make sure Bonta maintained powerful allies among the officers of the Alameda County Democratic Party Central Committee, Lacabe said. But the men had a schism after Bonta sought to replace Juarez as vice-chair of the local party committee with a different ally in 2016. But they apparently repaired their breach; in her declaration, Lacabe wrote that Juarez assisted “in securing Bonta’s Assembly seat for Bonta’s wife when Bonta became Attorney General” in 2021.

“He tried to make his real estate office the center of activity for Democrats.”

Lacabe told The Oaklandside that Juarez was able to make similar alliances with other local elected officials. “He figured out he could make political connections and people would hold their noses as long as he sends some money their way,” she said. “And it’s not even that much money because local political campaigns don’t cost that much.”

In 2020, Juarez offered his Fruitvale office on High Street to Councilmember Noel Gallo as a campaign headquarters, according to a lawsuit that was later filed against Juarez by his Fruitvale landlord. In 2021, Mia Bonta’s team also set up shop in Juarez’s building as she ran for Assembly.

When we first reached Gallo by phone, he, like others we reached out to for this story, burst out laughing when we told him we were writing about Juarez.

In a later call, Gallo confirmed that Juarez offered him the High Street office, and said he held some gatherings there but didn’t ultimately use it as a headquarters.

“I’ve known Mario and his family for many, many years,” Gallo said, adding. “They always volunteered” at community events. The Fruitvale office, which Gallo long thought Juarez owned until he found out otherwise, was a hub for several politicians and local figures, he said. Gallo recalled that when Juarez was there, the area around the property was “immaculate,” but after he left, trash piled up.

Gallo said he heard “on and off” about troubling business dealings involving Juarez, but said he stayed far away. “The other stuff he got involved with, I have no business with that,” he said. “I’ll leave it at that.”

Asked why he thinks Juarez built so many relationships with influential political figures, Gallo said, “He’s always been interested in running for politics.”

Even as Juarez cemented these alliances, he continued to pursue real estate deals, some of which landed him in hot water.

Making plays in biofuel and real estate

Mario Juarez’s former office building at 1241 High St. For over a decade, Juarez held political meetings in his office, in addition to running his real estate company and other enterprises out of the prominent Fruitvale location. Credit: Darwin BondGraham/The Oaklandside

Mario Juarez’s former office building at 1241 High St. For over a decade, Juarez held political meetings in his office, in addition to running his real estate company and other enterprises out of the prominent Fruitvale location. Credit: Darwin BondGraham/The Oaklandside

After getting his real estate license, Juarez began to build a diverse portfolio, as a broker of commercial and residential properties, a contractor, and a rent collector. One of his early sales, a residential duplex that went on the market in June 2005, quickly went wrong, resulting in the first of many lawsuits related to his new career.

In April 2006, the property’s buyer, an Oakland resident named Carlos Martinez, sued Juarez and one of his property companies, Fireside Realty, accusing them of withholding key information about a home. According to Martinez’s lawsuit, Juarez toured the property with him, advised him to make an offer on the house above the listed price, and helped line up a loan for him. Martinez claimed that Juarez “willfully” failed to disclose that the house had been illegally divided into a duplex and that a rear housing unit had been built illegally. After he bought the house for half a million dollars, Martinez claimed, city inspectors discovered the illegal unit and fined him.

Juarez and his brokerage “intentionally, willfully, maliciously, recklessly and unreasonably abused their superior position by concealing or failing to discover and disclose the true facts and material defects,” Martinez’s lawyers alleged. Juarez’s attorney denied these allegations, writing in a court motion that his client hadn’t made any claims about the house’s value or the legality of the second unit.

That case, paused for a time due to Juarez’s ongoing bankruptcy, reached a settlement in July 2008. The attorney who represented Martinez didn’t respond to an interview request.

Around the time of that settlement, Juarez persuaded a pair of Nevada developers, who operated as Boyd Real Property, to hire him to collect rent from tenants and renovate a commercial office space they had purchased at 4030 International Blvd., in Fruitvale, where one of Juarez’s companies was a tenant.

But the developers quickly soured on Juarez, according to a subsequent civil complaint, after they discovered he didn’t have a contractor’s license and had, they claimed, embezzled some of the rent he was supposed to collect. When Boyd tried to evict Juarez, the company claimed, he responded by encouraging other tenants to stop paying rent and dumping piles of trash and human waste on the property.

“This case is a real life nightmare version of the 1990 movie Pacific Heights,” Boyd’s attorney, Sandra Raye Mitchell, wrote in the lawsuit, filed in 2010. In the film, Michael Keaton plays a conman who moves into a swanky apartment and terrorizes his landlords, thwarting their efforts to evict him.

Mitchell declined to be interviewed for this story, but she appeared to have discovered Juarez’s troubled legal history when preparing her complaint. Juarez had “a long history, pattern and practice of defrauding creditors by forming undercapitalized entities such as corporations and limited liability companies,” she wrote, “incurring debts and then abandoning the entity and/or filing bankruptcy to discharge the debts and deny a recovery to the creditor.”

The developers claimed Juarez and his companies owed them tens of thousands of dollars. Shortly after filing the suit, Mitchell sought a restraining order, claiming that Juarez assaulted her during a visit she made to the property. He “pushed me, hit me and hit me in the face and then tore my clothes by ripping open the front and ripping off the buttons,” she wrote, adding that “he committed this violence to intimidate and drive me off the case.”

Juarez denied Mitchell’s claims and countered by seeking a restraining order against Mitchell, accusing her of a pattern of harassment and locking him out of the property. He also accused her of punching him on the head.

A judge issued an injunction against Juarez, which was later vacated on appeal.

While Juarez was pissing off his real estate clients, he had other irons in the fire.

In 2008, Juarez created a company called Viridis Fuels with Neal, the person who’d given him entrée into Alameda County Democratic circles. Viridis’ board of directors included Harris, the former Oakland mayor, along with major local corporate players, such as a Clorox director and the CEO of a regional bank. To supply the venture with money, Juarez tapped his real estate clients, promising them big returns that he repeatedly failed to deliver on, according to court records.

Juarez pitched Carlos Madrigal, an Oakland man he’d previously helped purchase a home, about investing in the biofuel project. In a subsequent civil suit, Madrigal claims the two met up at a carwash, where Juarez told Madrigal he could turn a $50,000 investment into a $150,000 return in three years. Madrigal was sold, but when he tried to get some of his money back in 2012, he claims Juarez refused to make him whole. A court dismissed the case in October 2024, with Juarez and Madrigal each agreeing to bear their own costs and attorneys’ fees.

Another pair of spurned investors had a similar experience, according to a complaint filed by Mauro and Hilda Bucio. The Bucios loaned Juarez $210,000 over the course of 2007 and 2008, which, they said in their civil suit, he failed to fully repay after the Bucios demanded payment. As he had with Mitchell, Juarez responded by filing for a restraining order against Mauro Bucio, whom he accused of insulting and hitting him, and pointing his fingers at him in a threatening way, as if he were going to shoot.

A judge ordered Juarez to pay the Bucios their loans with interest, totalling $338,000, but as of 2024, they had not received that money, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Even as Juarez became embroiled in litigation with his investors, he continued to push the biodiesel plant. In 2014, Juarez appeared at meetings of the East Bay Municipal Utility District, where he provided updates about the project. He and Neal acquired a lease to several acres of land near the former Oakland Army Base, and they applied for funding from the California Energy Commission.

After the commission rejected their application, Juarez turned to a powerful ally. Rob Bonta wrote a letter to the commission in 2014 recommending the project, and staff from Bonta’s assembly office urged the board to fund Viridis.

In 2015, several months after a judge discharged Juarez’s second bankruptcy case, citing his failure to pay creditors, the commission awarded Viridis with $3.4 million in funding. By then, Juarez and his various companies had been sued at least 11 times.

Viridis ultimately didn’t receive the state funds, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. The biofuel plant never moved forward as new legal problems for Juarez flared up.

Around this time, his real estate practices were attracting the attention of state regulators.

In December 2012, shortly after losing his second race for City Council, Juarez was hired by a commercial landlord who owned a small warehouse in East Oakland to find him a tenant. Juarez found a man who wanted to cultivate cannabis in the building. According to the terms of Juarez’s agreement with the landlord, he was to collect $3,500 in first month’s rent plus a $7,000 security deposit from the tenant, and Juarez would get to keep the first month’s rent as his commission.

But after receiving a tip, the California Department of Real Estate investigated and found that Juarez had ripped off the tenant by having him pay a $21,000 security deposit and a broker’s fee of $10,000 — and that Juarez gave the landlord a check for $7,000 and kept the rest for himself.

In 2015, Juarez voluntarily surrendered his real estate license.

The Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, then led by Nancy O’Malley, looked into the case as well, and the following year charged Juarez with felony grand theft and forgery. It would be his first criminal case, but not his last.

Juarez initially pleaded not guilty, and the DA later dropped the forgery charge and reduced the charge of grand theft to a misdemeanor, to which Juarez pleaded no contest. Juarez received a deferred entry of judgment, leaving his criminal record clean, and he was ordered to pay the tenant $23,000.

In February 2018, Juarez gave a $5,000 campaign contribution to O’Malley, who was running for reelection. Juarez listed “real estate broker” on the disclosure form, even though he’d surrendered his license three years earlier.

A would-be entertainment mogul

The now-shuttered Oakland Megaplex nightclub at 200 Hegenberger Rd. Juarez’s attempt to work with the owners to convert it to a Latin music venue resulted in litigation. Credit: Screenshot from Google Maps

The now-shuttered Oakland Megaplex nightclub at 200 Hegenberger Rd. Juarez’s attempt to work with the owners to convert it to a Latin music venue resulted in litigation. Credit: Screenshot from Google Maps

The 2010s saw Juarez launching yet another career, in nightlife and entertainment.

This foray, too, would result in multiple lawsuits — sometimes with Juarez as the plaintiff.

In 2015, he and two business partners approached the owners of a nightclub on Oakland’s Hegenberger Road with a proposal to convert it into a venue for Latin music and together launch a company called Latin Power Presenta. The club owners, Michael and Gloria Govan, agreed, Juarez later claimed. One year later, Juarez would sue the Govans, along with his own partners, claiming he’d invested $90,000 into the venture but had been frozen out of the business because he was uncomfortable with a slew of shady business practices.

Juarez also accused his other two partners of “improper relationships” with female employees and other unscrupulous behaviors, according to a lawsuit he filed in May 2016.

The Govans, who did not respond to a request for an interview, denied most of Juarez’s allegations, including that he had contributed $90,000 to the company.

“Apparently, Juarez, who has an extensive and checkered past, is known for not following through on his business promises and for leaving others holding the bag,” the Govans’ lawyers wrote. It’s not clear from court records whether the case was resolved, and the Govans were on the receiving end of a couple other lawsuits in the years following Juarez’s.

One month after he filed the nightclub suit, Juarez won a second term on the Alameda County Democratic Party Central Committee. But his music promotion business continued to run into trouble.

In 2020 Juarez filed lawsuits against two prominent Mexican rock bands — El Tri and Victimas del Doctor Cerebro — who’d hired his Mario Juarez Entertainment Company as the promoter for their US tours.

Juarez sued El Tri and their production company that March, arguing he was owed a cancellation fee after a number of shows he’d booked fell through. El Tri and the band’s production company, Lora Productions, denied they played any role in the canceled shows, calling Juarez a “wannabe music promoter” who misled them and owed them a cancellation fee instead.

On top of neglecting his duties as promoter, the band claimed in a response to Juarez’s suit, Juarez bounced a $20,000 check for band travel and made an unauthorized purchase using the credit card of a real estate broker.

That broker, Manhaz Khazen, told us she first met Juarez years ago, when a mutual connection introduced them at a country club. At the time, Khazen was looking for a buyer or new tenant for the historic Lake Merritt Lodge property, which she owned. Juarez, she said, connected her with O’Malley, the DA, who toured the property as a potential site for a women’s shelter she was looking to launch. (That plan didn’t pan out.)

Around this time, Juarez called Khazen to ask for a donation for an artist he was representing, who was apparently stranded somewhere and couldn’t afford to get to a music festival where they were scheduled to perform. Khazen said she’d buy the musician a festival ticket, but Juarez insisted on using her credit card number to handle it himself. Knowing Juarez as a fellow broker trusted with a “very credible entourage,” Khazen agreed.

“Next thing I know, American Express calls me and says, ‘Do you know you’re buying 53 tickets?’” Khazen recalled. “I said, ‘What am I doing, bringing the whole symphony?’”

When she confronted Juarez, she said, he blamed the mix-up on the travel agent. Khazen recalled telling Juarez she’d take him at his word and let it go.

Khazen described Juarez as an ultra-connected figure that no one wanted as an enemy.

“He can maneuver very easily,” she said.

The El Tri case was dismissed in 2021. Court records don’t indicate whether a settlement was reached. A lawyer who represented Lora Productions said he didn’t recall the details of the case.

“Next thing I know, American Express calls me and says, ‘Do you know you’re buying 53 tickets?’”

The same month as he sued El Tri, Juarez sued Victimas del Doctor Cerebro, this time for defamation and libel. Juarez claimed he booked five shows for the band, then sold the opportunity to handle those shows to a publicist — who then failed to sell tickets to the shows. When Juarez delivered this bad news to the band, the musicians and their fans took to social media, excoriating Juarez and encouraging others to pile on. One defendant in the case called Juarez, on social media, a “pseudo-promoter” who “swindled” the band.

Juarez sought $2 million in damages, but the case was dismissed in 2023 after he failed to show up to hearings.

It was during this period that Juarez’s relationship with Neal, his political patron and business partner, soured.

Neal ran a nonprofit, the Oakland Community Fund, which is described in tax filings as sponsoring business luncheons and administering grants, and she had brought Juarez onto its board. According to court records in a 2021 criminal case, Neal discovered in 2017 that Juarez had embezzled $45,000 from the nonprofit.

“He came to a board meeting one day and said he had a way for the nonprofit to make some money,” Neal told The Oaklandside. “We checked out the plan with our attorney and they said it was okay.”

The plan was for the nonprofit to provide a small home loan to a woman in Oakland, who would pay back the loan with interest. However, when she paid it back, Juarez pocketed the funds for himself, a deputy district attorney alleged in the 2021 embezzlement case against Juarez.

Neal said she discovered the problem when she wrote the woman to ask why she hadn’t paid the loan back. “She sent me back all this documentation showing she’d paid Juarez,” Neal said. “I recommended she go to the district attorney.”

In a letter to the borrower claiming the debt would be canceled, Juarez had signed his name and attached an expired real estate license number that belonged to a deceased agent, according to the Oakland police officer who investigated the case.

Juarez’s attorney, Charles Bonner, argued that Neal and her organization were falsely portraying themselves as victims; he sought to subpoena business records from the Oakland Community Fund and Neal’s consulting business. When Neal didn’t comply with the subpoenas — she told us she had a stroke and couldn’t respond — the DA’s office dismissed the case. Juarez, once again, emerged unscathed.

Juarez the ‘co-conspirator’

Copies of the mailers created by Mario Juarez and sent to thousands of Oaklanders days before the 2022 mayoral election. Credit: Darwin BondGraham

Copies of the mailers created by Mario Juarez and sent to thousands of Oaklanders days before the 2022 mayoral election. Credit: Darwin BondGraham

Between 2020 and 2022, Juarez used his High Street rental property to host campaign events for Councilmember Noel Gallo — Juarez’s former opponent — and for Assemblymember Mia Bonta. And he spent large sums backing Sheng Thao’s campaign for mayor. In November 2022, Juarez used an independent expenditure committee to spend over $110,000 on mailers attacking two of Thao’s opponents, Loren Taylor and Ignacio De La Fuente, whom he’d once tried to unseat on the City Council. This expenditure would later be referenced in connection with Co-conspirator 1 in the federal corruption case against Thao.

But for all his magnanimity, he was allegedly jilting his landlords for their rent.

The High Street office space was owned by the Ye family, who were first-generation immigrants. In 2017 the landlords tried to evict Juarez after discovering he had built a “high-end residence” inside the building, though Juarez convinced them it was just a showroom to promote his real estate development business, according to court records.

Then in 2021 the Ye family again tried to give Juarez the boot, accusing him of illegally living on the property — and failing to pay the rent. Juarez argued that he was “seriously impacted financially” during the pandemic and his family had to secretly move into his office space to quarantine. He also argued that since the office was now their primary residence, they were protected by Alameda County’s COVID-era eviction moratorium.

The Ye family shredded Juarez’s story in a court motion. He had an apartment in Fruitvale and, far from being penniless, Juarez had spent nearly $4.4 million to purchase a property next door. “The claim that Defendant Juarez is a charity case is a hoax,” the Ye family’s’ attorney, Robert Riggs, wrote in a court filing. “His family is well connected.”

Riggs did not respond to an interview request.

In February 2023, a judge ordered Juarez to return the property to his landlord and pay costs. The Ye family claimed that Juarez owed $268,000.

Meanwhile, a real estate deal that Juarez was working on next to his landlord’s property would attract legal scrutiny.

In late 2021, an investor for a group called Balboa LLC was approached about lending $3 million to Juarez. Juarez secured the loan, and later he also got a $250,000 loan from Stewart Chen, a local businessman and head of the Oakland Chinatown Improvement Council. The problem, according to an investigation by the district attorney’s office, is that Juarez used the same real estate as collateral for both loans — two properties he owned on East 12th and High streets. And Juarez didn’t tell Chen that his loan was second in line to be repaid if the property was foreclosed, meaning he ran a big risk of not being repaid.

These allegations are laid out in an affidavit filed by David Bettencourt, an Alameda County District Attorney’s inspector, who in July 2024 was seeking a search warrant to obtain Juarez’s banking records. Bettencourt had begun investigating after Chen submitted a complaint, which ended up with the DA’s real estate fraud unit. The DA’s office did not respond to an inquiry about the status of the investigation.

According to Bettencourt’s affidavit, when Chen confronted Juarez about the collateral issue and missing loan payments, Juarez responded by approaching Chen’s wife and claiming, baselessly, that Chen had hired prostitutes. Chen described it as an act of intimidation to get Chen to stop “pressuring Juarez to make good on their loan.”

One of the Balboa investors also said he’d been threatened, telling Bettencourt that Juarez said he’d cause “him a lot of trouble in Oakland” if he tried to foreclose on the property.

Bettencourt noted in his affidavit that he had spoken with three individuals “who appear to have been victimized by Juarez, who in each case used pressure to persuade otherwise wary investors into funding him or continuing to fund him, and in each case failed to pay back or deliver what was agreed upon.”

“It is clear Juarez is prone to using tricks, deception, lies or omissions to not only secure payments, but to stall the lenders when they begin to ask for agreed on payments, then resorting to threatening language and behavior when the lenders begin losing patience and pressing for payment,” Bettencourt wrote.

Bettencourt wrote that he believed an examination of Juarez’s bank accounts would turn up proof that Juarez committed two felonies by deliberately misstating facts about the balance of his bank account on a loan application to deceive a potential lender.

Balboa foreclosed on the property in December 2022. Criminal charges have not been filed.

But that investigation touched on the issues at the heart of the federal investigation that resulted in the FBI raid on Mayor Sheng Thao’s office in June of last year.

The Bettencourt affidavit details complaints by David and Andy Duong, who would later be named as Thao’s co-conspirators, that Juarez had bilked them out of an $800,000 investment in a housing business that would build low-cost container houses in Mexico for the Oakland affordable housing market.

The deal Juarez and the Duongs put together resulted in a new company called Evolutionary Homes.

Federal prosecutors say Evolutionary Homes became the centerpiece of an audacious conspiracy to bribe public officials in Oakland and beyond. According to the indictment unsealed in January, the Duongs and Juarez believed that Thao, if elected, would grease the wheels for their housing company to earn millions in city contracts. In pursuit of this, prosecutors claim, Juarez set up the committee that spent $110,000 on the mailers attacking Thao’s main opponents in the race.

Thao won — and things rapidly went downhill.

Thao met with officials from Evolutionary Homes in 2023, according to her appointment calendar. And Thao went on a government junket to Vietnam, paid for by a Vietnamese business association controlled by the Duong family. But the city council never publicly considered or voted on a contract for the company. Juarez and his team, including Andy Duong, also pitched Santa Clara County Supervisor Cindy Chavez and Alameda County Supervisor Nate Miley, but no one was biting, according to public records.

The company was becoming a money pit. The Duongs invested roughly $1 million, much of it to pay for the construction of dozens of container homes. But Juarez only delivered a couple completed homes and was pressuring the Duongs to pay more, according to the affidavit.

Andy Duong, right, attends a hearing at Oakland’s federal courthouse on Feb. 6, 2025. Duong and his father were in business with Juarez until a falling out in early 2024 and explosive allegations of violence and corruption. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

Andy Duong, right, attends a hearing at Oakland’s federal courthouse on Feb. 6, 2025. Duong and his father were in business with Juarez until a falling out in early 2024 and explosive allegations of violence and corruption. Credit: Estefany Gonzalez for The Oaklandside

By 2024, Juarez was in dire financial straits, according to public records. He owed tens of thousands in unpaid taxes to the state and federal government going back nearly two decades. In May, a lender received a nearly $33,000 judgment against him after he failed to make payments on his 2012 BMW 7-Series.

That year, Juarez was hit with another criminal investigation, this one related to those attack mailers. The shop that had printed Juarez’s attack mailers claimed Juarez’s checks had bounced, and the DA’s office, then led by Price, charged him with fraud.

As was his habit, Juarez lashed out, claiming that Price was retaliating against him for turning down a demand for $25,000 to fight the recall campaign she was facing. Price’s office addressed these claims in subsequent filings, and Price later accused Juarez of being “a crook.” In court filings, Price wrote that if she was recused from the case, the state should appoint a special prosecutor and recuse Bonta, citing his “close financial and political ties” with Juarez.

As pressure mounted, Juarez’s relationship with the Duongs collapsed. In early May 2024, Juarez had an altercation with the Duongs outside their office at 1211 Embarcadero St.

In a letter to the port commission, which owns the property housing the Duongs’ office, Juarez claimed that he confronted the Duongs about illegally locking him out of the Evolutionary Homes office, also located in the building on Embarcadero. He claimed the Duongs summoned a group of people who beat him until he convulsed, and stole his watch and jewelry.

In his own letter to the Port, David Duong dismissed Juarez’s allegations as “bizarre and disturbing.”

In mid-June, shots were fired outside of Juarez’s home. He told police he believed the attack was in response to his involvement in an unnamed investigation.

Two weeks later, agents from the FBI and the IRS raided the home where Thao lived with her partner Andre Jones. Agents also hit properties belonging to David and Andy Duong. The raids set off political upheaval across the city.

What drove them wouldn’t be made public until January 2025, when federal prosecutors unsealed an indictment, heavily reliant on Co-conspirator 1’s claims, that accused the Duongs, Thao, and Jones of the brazen bribery scheme.

It’s a mystery why Thao and the Bontas associated themselves with a man who’d wracked up two decades of civil suits, criminal indictments, and financial judgments.

“He knows how to weasel his way into relationships,” Neal told The Oaklandside. “I’ve tried to warn people to steer clear from him.”

Drake, the Democratic central committee member, said she thinks the Duongs may have gotten into business with Juarez, despite his history of bitter legal disputes, because of what he offered. “He must have told them he had all kinds of ins with the city administration,” she said.

Juarez tweets from Dubai two months after the indictment comes down.

Lacabe, the other central committee member, said she believes powerful figures got close to Juarez because of — not despite — the controversy that swirled around him. “He’s dirty, as people who play politics in the Bay Area are,” she said.

De La Fuente said he, too, suspects that many business and political figures made alliances with Juarez because he was someone who would do unseemly things. “They knew he was a crook, but they wanted to use the guy,” he said.

De La Fuente speculated that Juarez may have evaded criminal convictions over the years by becoming a valuable source for the police. “The FBI, they want to get a few elected people,” he said. “They use everybody.”

David Duong and his lawyers now claim, in a recent motion filed on Oct. 31, that the extensive history of civil and criminal fraud accusations against Juarez could raise serious questions about the veracity of the information he handed to the feds.

In March, two months after the federal corruption indictment came down, Juarez traveled to Dubai, posing in front of an art installation of giant wings on the 124th level of the Burj Khalifa.

“Still flying,” he wrote on X. “Some are about to hit turbulence.”

“*” indicates required fields