Over the next six weeks, Oakland plans to install 18 speed cameras that will lead to the automatic ticketing of drivers who exceed the speed limit by more than 10 miles per hour. They will be the first speed cameras in the city in 11 years, since a handful that had been installed were turned off or taken down after privacy advocates successfully argued that their use risked violating residents’ civil rights.

During that time, Oakland’s speeding issues have persisted. The Oakland Police Department said two years ago that speeding, running of red lights, and the failure to yield were the leading causes of collisions in the city that led to serious injuries or deaths. The Oakland Department of Transportation said that in the city’s most dangerous corridors, known as its high injury network, speeding was the single leading cause of crashes that injured pedestrians.

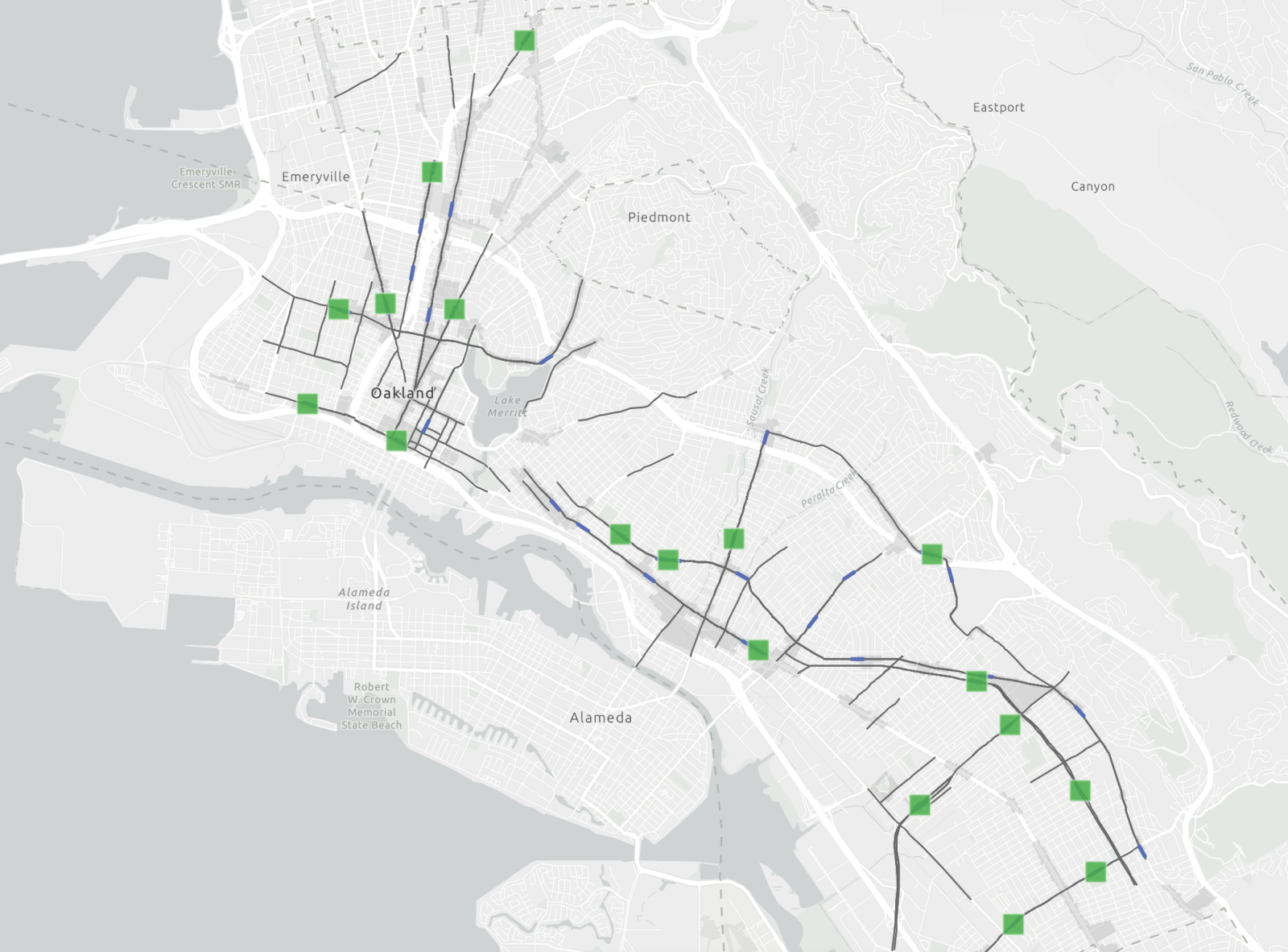

The cameras will all be posted on major roadways in Oakland’s high-injury network.

Two on 98th Avenue, one near Birch Street and one near Church Street

Two on Bancroft Avenue, one near 65th Street and one near 86th Street

Two on Foothill Boulevard, one near 19th Avenue and one near 24th Avenue

Two on 7th Street, one near Adeline Street and one near Broadway

One on Hegenberger Road, near Hawley Street

One on 73rd Avenue, near Fresno Street

One on MacArthur Boulevard, near Enos Avenue

One on International Avenue, near 40th Avenue

One on Fruitvale Avenue, near Galindo Street

One on Broadway, near 26th Street in Uptown

One on Martin Luther King Jr. Way near 42nd Street

One on San Pablo Avenue, near Athens Street

One on West Grand Avenue, near Linden Street

One on Claremont Avenue, near College Avenue

Dark gray lines indicate Oakland’s high-injury network, and green squares indicate the locations of the new cameras. Credit: OakDOT

Dark gray lines indicate Oakland’s high-injury network, and green squares indicate the locations of the new cameras. Credit: OakDOT

The new cameras will trigger an automatic ticket for drivers who exceed the speed limit by 11 miles per hour or more and send the ticket to the registered owner’s address. The penalties will increase as people drive faster, with drivers who exceed the speed limit by 11 to 15 miles per hour getting a $50 fine. The maximum fine will be $500 for drivers who exceed a road’s speed limit by 100 miles per hour.

Money generated from this program will be used to pay for “traffic calming measures,” according to the city.

Mayor Barbara Lee issued a statement saying the speed camera program was a “smart, life-saving step forward and brings us closer to streets where everyone can travel safely.”

OakDOT’s director, Josh Rowan, said his team was excited about the program and “confident it will make a meaningful difference.”

Most of the cameras will be placed in the middle of neighborhood blocks, not at intersections, in East Oakland and Downtown. All of the streets getting cameras are arterial roads with heavy traffic that cross through business or school districts. Many connect directly to state highways.

OakDOT said today that those locations were chosen based on the “crash data and speed studies” that underlie the agency’s High Injury Network. Those studies have found that some locations, which were not specified, “saw more than 10,000 vehicles traveling at 11 mph or more over the posted speed limit in one day.”

The city of Oakland says it will start sending warnings to speeding drivers in mid-January. After a 60-day period, the city will begin to issue fines.

The cameras will be provided and installed by Verra Mobility, an Arizona-based company. Verra has run the camera system for New York City for years. An audit there two years ago by the city’s comptroller found that while speeding at the camera locations had declined, a high number of the citations were rejected over missing or obscured license plates and the city had overpaid Verra for several cameras that were inactive or offline.

A state pilot

The camera installation comes two years after Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 645, which approved their use in six counties, including Alameda County. The legislators who shepherded the bill through the legislature that year, including Southern California Rep. Laura Friedman, cited a 2020 report by California’s Zero Traffic Fatalities Task Force, which used research that found speed camera use in key road sections can improve community safety.

Oakland is the second city in the state to implement the new speed cameras after San Francisco, which began installing them in March and started issuing tickets in August. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the city’s dozens of cameras were issuing about 600 tickets a day by early October, and that 90% of the tickets were for drivers traveling between 11 and 21 miles per hour over the speed limit. That would mean more than $10 million in city revenue over the course of a year if all the tickets were paid. San Francisco has twice as many cameras as Oakland will have because the law capped the number of cameras allowed in each city based on population.

Los Angeles, San Jose, Glendale, and Long Beach are also planning to add the cameras in the coming years.

The state will evaluate the efficacy of the speed cameras in 2032, when the law allows an option to expand them to other cities or end the pilot project.

Concerns about privacy

Previous usage of speed cameras in Oakland ended over privacy concerns. Organizations such as Oakland Privacy, a local advocacy group, argued that footage from video cameras could be used to track people without residents’ consent and then potentially abused by law enforcement.

Justin Hu-Nguyen, the co-director of Bike East Bay, which advocates for road safety, told us then that he hoped for a citizen’s advisory committee to oversee the speed camera program. But he saidt the city did not take action. “On details not legislated into the bill with less oversight and accountability, the cities don’t have the incentive to make them happen on their own,” he said.

Hu-Nguyen said that a commission would help city residents make sure that the city is adhering to the law correctly, including knowing how the city spends the money it will receive from speeding tickets — and how the city will protect residents’ privacy.

“The experience with the city’s Flock cameras have found that data safeguards are only as good as the weakest link, so how is data being taken care of and what happens, for example, with federal immigration enforcement?” he said. “We want to make sure that things are transparent to the public.”

Hu-Nguyen said that more cameras in already surveilled communities can make residents less open to engaging with law enforcement.

The law as signed by Gov. Newsom included some provisions intended to address privacy concerns.

For example, the cameras will take digital photos of license plates and not of the driver’s windshield, a view that might capture the faces of drivers or passengers. The law does not allow the cameras to take video or deploy facial recognition technology. The latter technology would require vast amounts of data, including images of private citizens who abide by speed limits, and has been found to misidentify people, including, according to a study, misclassifying Black women almost 35% of the time. Another provision of the California law requires that photos from these cameras be deleted after five days if there is no violation and after 60 days if there is a violation.

A disproportionate impact

When the law passed, Tracy Rosenberg, a volunteer with Oakland Privacy, said that though many of her privacy concerns had been mitigated, she still worried that automated ticketing was a form of financial extraction that would most harm low-income communities who simply can’t afford it.

In an interview today, Rosenberg told The Oaklandside that it was important for Oakland residents to understand that advocacy over the years led to a much better law than the bill that was first introduced. She said she remains concerned about the economic impact the cameras would have on low-income communities.

There are some provisions in place to protect low-income residents. California Vehicle Code Section 22429 allows people to seek a 50 to 80% reduction in any fine if they are indigent or low-income or allows people pay fines through community service.

“There are accommodations to help people in extreme financial circumstances pay the ticket, but there’s still going to be a disparity impact to working class people,” Rosenberg said. “If you use a road with a camera consistently, ‘cause you’re rushing or have something on your mind, or whatever it is, you’ll find that tickets add up in a serious way.”

Rosenberg noted that the fees themselves are lower than they could have been. The $50 fine for the lowest speeding infraction is less than most parking tickets in Oakland, for example.

Rosenberg said that the speed cameras may help inform the city as it makes long-term road infrastructure improvements. She noted that San Francisco’s initial data showed that only a handful of cameras were issuing the most tickets, which were linked to road design issues that encouraged speeding — literal built-in speed traps.

“That’s the highest and best use of this program,” she said. “To fix the roads where we need to fix them.”

“*” indicates required fields